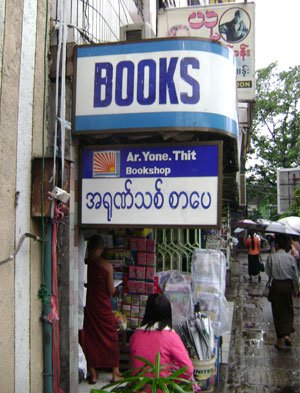

At the Sule Pagoda, the gilt and marble temple at the center of the old city, and also at the Shwedagon Pagoda, the massive, luminous, hilltop temple north of the city where Buddhists burn incense and press their foreheads to the marble pavilions beneath carved icons and golden spires, there are arcades with bookstores selling copies of the ancient Pali texts—the canon of Theravada Buddhism—that formed the entirety of the written word here before the arrival of the British in 1824. (By 1886, the country had been established as a province of British India; in 1937 it became a separate, self-governing colony; eleven years later, the nation became an independent republic, but democratic rule ended in 1962.) In addition to the original texts, modern novels based on the religious stories are popular in the bookstores that dot the city's downtown.

The helpful owner of the Bagan Bookshop, located in two neat rooms on Thirty-seventh Street, searches his shelves for me and locates a bootleg copy of the stories of Burmese writer Thein Pe Myint. An American graduate student, Patricia M. Milne, who worked under Anna Allott, the English grande dame of Burmese literary studies, translated the book in 1975. Thein Pe Myint wrote in the 1930s and 1940s while he fought for freedom from the British, and he offers the native alternative to Orwell's imperial perspective. The opening story in the book begins with news of a storm: "The banyan and tamarind trees were swaying, while the smaller trees and bushes were practically prostrate, just like little chickens cringing in fear of a kite." I read these lines as cyclone winds begin to break over the city, causing the corrugated tin roof of the home beneath my hotel window to flap and bang.

Short stories deemed acceptable by Burmese censors generally follow the socialist realist model. They are patriotic or nationalist; they promote selflessness; they say something nice about love or hard work; they end with a moral. I meet with the short story writer and translator U San in a crumbling, colonial-era villa not far from the vast new American embassy, a short drive from the Shwedagon Temple. A taxi drops me by the open gate, and I walk up a short driveway, past an overgrown lawn, onto a rotting porch where I tug on a tarnished brass pull. U San answers the door in a white singlet and a green plaid longyi, the traditional sarong-like garment worn by both men and women in Myanmar. Like all the writers I meet with in Myanmar, U San can speak English. After some brief pleasantries, he tells me he is upset because the censor has just rejected an article he wrote.

"It was supposed to go here," he says, holding up a newspaper and showing me the advertisement that occupies the space on the page where his article was scheduled to appear. "There was nothing political in it. It was an article about the Burmese language. The censor just didn't agree with my perspective."

He leads me into a pleasant sitting room with high ceilings and a towering glass-fronted mahogany cabinet crowded with small icons. The collection includes numerous brass bodhisattvas, a porcelain Chairman Mao smoking a cigar in a wicker chair, and a bust of Shakespeare. An accomplished teacher in his sixties, U San has a slender aristocratic bearing and thinning white hair that he sweeps straight back across a mottled scalp. In between lectures about the evolution of the contemporary short story in Myanmar, he fusses and shuffles about like the unassuming detective Father Brown in the old G. K. Chesterton stories—a clever man projecting a simple facade. He offers me tea, but then forgets to bring it and instead returns with a stack of his translations.

"I haven't written any stories since my student days," he says. "I'm a translator." He shows me his first anthology of translated stories, published in 1969. "It was a best-seller and went through three editions. Before this, Burmese stories were just nursery rhymes and Pali tales, but afterward, they began to experiment."

The anthology is a paperback survey of writers from the Western canon. It starts with Defoe, offers excerpts from Austen, Hawthorne, and Dickens, then samples the American modernists and ends with a story by Updike. Over the course of the 1970s, the collection transformed the Burmese writing scene and drew criticism from Burmese academics, who accused its translator of promoting Western tastes and values at the expense of Burmese traditions, U San says. In the years since, he has published other translations that cover the same basic periods, but he supports himself through his teaching.

He explains that the first Western-style novel to be printed in Myanmar was a retelling of The Count of Monte Cristo. Around 1900, the Burmese writer James Hla Gyaw published Maung Yin Maung Ma Me Ma, which reset the Dumas novel in Burma and proved to be very popular.

U San lifts one of his own anthologies. "I had to change the name of this one. I named it A Jury of Her Peers after the Susan Glaspell story that is in it. But the government thought the her was Suu Kyi," he says, referring to the leader of the Myanmar opposition party who has been under house arrest for thirteen of the last eighteen years. "I had to change it before the publisher could release it."

I glance out the window, beneath a dusty curtain, and watch an Indian almond tree swaying violently. Earlier in the day I was at the American Cultural Center, where an American acquaintance warned me that a cyclone was going to strike Yangon later that evening. U San says he has heard about the coming storm from a friend. Although U San is hospitable, I'm worried that the rains will begin and I'll be stranded with him. After a bit more polite discussion, I apologize and walk back to the road to find a taxi.

As I'm thanking him, I ask him how much I can quote from our conversation for this article. He offers me a bemused Father Brown smile and says, "I have said nothing political." I nod but am not sure what to think. His complaints about the censors are clearly political. In the end, the threat posed by the junta has forced me to change his name and alter descriptions of his home.