Kurt Vonnegut Jr. once described Hunter S. Thompson’s books as the literary equivalent of cubism: “All rules are broken.” To that, many readers would add that Thompson helped fashion new ones. Along with Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, and others writing in the late 1960s, he pioneered a new, first-person, often present-tense, novel-like reporting that was labeled “New Journalism.” This hybrid gave the reporter a central role in his narrative, and Thompson took it even further. Without him, there was no story. His reporting was a mad mixture of serious social and political commentary intertwined with explosive descriptions of his own drug-laden, hard-drinking, outlaw life. Now, after his suicide at his home near Aspen, Colorado, on February 20, we are left to debate his legacy. Will we be more interested in his life or his literature? Which is more compelling: his celebrity or his sentences?

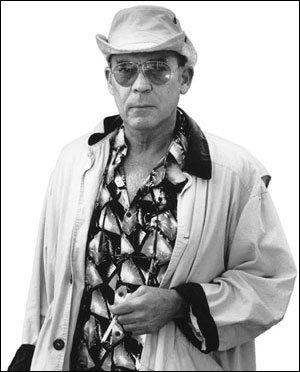

To those who knew him through his work—and, if we are to believe the many tributes published in the past two months, to those who knew him intimately as well—Thompson was a strange and lovely amalgamation: a strung-out-rock-star-pistol-toting-liberty- loving-beat-poet-genre-busting- novelist-newspaperman-husband- father-grandfather. He chased the big lie and the big liar, breaking journalistic ground while following his unique psychic beat: fear and loathing everywhere. He wrote intermittently, hammering away at hypocrisy, exposing America's faults and frailties while sharing what were obviously his own.

In the minds of some readers and critics, Thompson’s larger-than-life persona overshadowed a slight literary contribution. But this complaint never diminished the spectacle. Thompson continued to lace his serious work on popular culture and politics with his dark affections: drugs, drinking, violence, and debauchery. He covered what troubled and fascinated him

Born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1937, Hunter S. Thompson joined the Air Force just after graduating from high school. In 1956, while at Eglin Air Force Base in Niceville, Florida, he began covering sports for the base newspaper. Early in his career, he wrote for local papers and wrote freelance articles for magazines.

In 1965 he wrote a piece for the Nation, about the Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang, that caught the attention of New York book publishers, and in 1967 Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs was published by Random House. His complete bibliography includes some 14 books, including two works of fiction. A film based on Thompson’s only published novel, The Rum Diary (Simon & Schuster, 1999), is currently in production and slated to star Johnny Depp and Benicio Del Toro.

Thompson’s most successful and best-selling work remains Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, a semifictional account of tripping on LSD, ether, and other drugs while covering the fourth annual Mint 400 motorcycle race and the National District Attorneys Association’s Convention on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs in Las Vegas in 1971. He followed that book up in 1972 with Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail, which detailed the U.S. presidential race between Richard Nixon and George McGovern. Both books were first serialized in Rolling Stone, where Thompson worked as a contributing writer. Thompson’s famous distaste for Nixon was deep and lasting. In “He Was a Crook,” the obituary of Nixon that appeared in Rolling Stone, Thompson wrote: “His casket [should] have been launched into one of those open-sewage canals that empty into the ocean just south of Los Angeles. He was a swine of a man and a jabbering dupe of a president.”

It was mainstream reporting penned in incantatory language that separated Thompson’s writing from that of other working journalists. He often mixed sports and politics, giving them equal importance in his writing. Some of his last good work, in fact, was published online by ESPN. He was serious about taking social and political commentary to the masses, and he did. He insulted, enraged, and engaged generations and made us interested in what interested him, even by the manner of his death.

The details of Thompson’s last moments varied according to the news outlet reporting them. The New York Times reported that Thompson “died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound at his home in Woody Creek, Colorado,” while Troy Hooper, of the Aspen Daily News, explained further that he “shot a .45 caliber bullet into his mouth Sunday night.” Hooper went on to quote Thompson’s widow, “I was on the phone with him, he set the receiver down and he did it. I heard the clicking of the gun.” In addition to the gory details, the nation remains fascinated by Thompson’s last wishes, primarily that he be cremated and his ashes blasted from a cannon at his home in Colorado.

The number of notable tributes that have followed Thompson’s death is extraordinary. Tom Wolfe wrote in the Wall Street Journal, “Hunter’s life, like his work, was one long barbaric yawp, to use Whitman’s term, of the drug-fueled freedom from and mockery of all conventional proprieties that began in the 1960s. In that enterprise Hunter was something entirely new, something unique in our literary history. When I included an excerpt from Hell’s Angels in a 1973 anthology called The New Journalism, he said he wasn’t part of anybody’s group. He wrote ‘gonzo.’ He was sui generis. And that he was.”

Even with big names vouching for Thompson’s enormous talent, perhaps even his “genius,” his legacy is not yet fixed. But many memorials offered by practicing writers and journalists paid homage to his deep influence. He was a man of certain bravery and bravado whose work will likely remain on our minds for decades to come.

Joe Woodward is the author of Small Matters: A Year in Writing.