John Biguenet was born in New Orleans, where he is the Robert Hunter Distinguished University Professor at Loyola University. The winner of an O. Henry Award for short fiction, he is the author of the novel Oyster (Ecco, 2002) and The Torturer’s Apprentice: Stories (Ecco, 2001) among other books, as well as such prizewinning plays as Night Train (2011), Shotgun (2009), Rising Water (2007), and The Vulgar Soul (2005). Named its first guest columnist by the New York Times, Biguenet chronicled in both columns and videos his return to New Orleans after its catastrophic flooding and the efforts to rebuild the city.

![]()

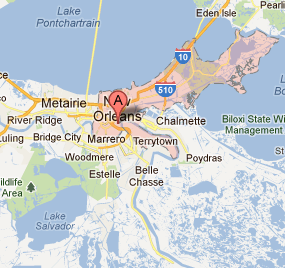

The night before defective levees designed and built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began to collapse all across New Orleans, killing over 1,000 American citizens and destroying one of the world’s great cities, nearly 500,000 New Orleanians lived here. According to the latest census, not quite 350,000 people now populate the city. But over half of the faculty at Loyola University, where I work, have moved to the city since 2005, a percentage that probably holds true for the entire current population. So perhaps as few as 175,000 preflood New Orleanians still live here. Ours is a culture that remains in crisis and is yielding, little by little, to a much more Americanized way of life.

The influx of newcomers makes sense; they are finding great opportunities here. Gutted homes can still be had for $60,000. Young teachers from around the country have filled the classrooms of the many charter schools that replaced most of the existing Orleans Parish public schools after more than six thousand veteran local teachers were fired in a single day, a few months after the levee collapse. And considering the quality, the food and the music of the city remain a bargain. So, perhaps unsurprisingly, New Orleans is a somewhat younger, richer, and whiter place than it used to be.

To a careful eye, though, postflood New Orleans is a palimpsest; here and there, the past bleeds through the fresh culture now being inscribed over the submerged text, centuries old. Still, for writers new to town—even those attentive to the occasional glimpse of its traditional life—it is a difficult place to comprehend and depict with any hope of authenticity. Like much of Europe, the city maintains a division between public and private life. The face it offers a stranger is almost always a mask.

Last spring, for example, I attended a friend’s funeral at a small, predominantly African American church across the river, followed by the congregation’s “repast” in the afternoon. The morning’s service was nearly three hours long as thunderous preaching alternated with gospel music that lasted twenty minutes a song. After an hour or so, the border between speaking and singing began to muddy, and the missionary sisters in their black-and-white dresses and elaborate hats would fall into song even as they offered eulogies of our friend.

Over here on this side of the river, the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival was in its final weekend with a whole tent dedicated to gospel choirs. How different it was for the tourists and the new New Orleanians in that tent, swaying to what for them could be only a show, compared to all of us in that church, where the music was not a performance but a prayer meant to comfort our grief. And how different was the poetry of the pulpit, as the rolling rhythms of the preacher returned after flights as improvisational as a jazz riff to the scripture his sermon meant to elucidate, phrase by phrase, to buttress the faith of the family weeping beside the open coffin.

Spent after the daylong funeral and feasting, my wife and I attended an art opening that night by an artist with whom I became friends after he had read my novel, Oyster. As I do in that book, he has been recording the passing way of life in Plaquemines Parish—oyster boats half-sunk on their reefs, shrimp boats returning to moorage at dawn with their nets spread like huge lace wings to dry after a night of trawling, egrets wading along mudflats, oil rigs rising over the dying wetlands. Afterward, he threw a party at a raggedy bar on the edge of the Lower Ninth Ward. (You have to ring a bell to be admitted so the place won’t get robbed.) It’s got the best jukebox in the city, mostly local brass bands and musicians who refuse to go north and get rich. You wouldn’t guess it from the street, but it is a very New Orleans spot to drink, with a five-year-old sitting on a stool at the bar drawing pictures of his mother that night, two dogs wandering from table to table, a pot of jambalaya somebody made warming next to a basket of sliced French bread, and two old women arguing about a cousin who wouldn’t pay rent. Then Etta James started singing “At Last” and all the couples—twenty-year-olds, eighty-year-olds—found room to dance.

New Orleans is a city that’s almost always on the other side—of a river, a locked door, a mask—from where you are. One of our most famous French Quarter restaurants boasts an ornate entrance of cut glass, but before the flood, only tourists entered there. Down the block was an unmarked door where New Orleanians knocked when they had reservations. It’s that kind of city—or at least it used to be.

Writers have sought to peek behind the city’s veil for many years, and for good reason. As author Lafcadio Hearn (whose home at 1565 Cleveland Avenue is preserved as a literary landmark) explained in an 1879 letter to a friend in California, “Times are not good here. The city is crumbling into ashes. It has been buried under a lava flood of taxes and frauds and maladministrations so that it has become only a study for archaeologists. Its condition is so bad that when I write about it, as I intend to do soon, nobody will believe I am telling the truth. But it is better to be here in sackcloth and ashes than to own the whole state of Ohio.”

Bookstores

Bookstores

One of those visiting authors was, of course, William Faulkner, and the first place a writer new to town should visit is Faulkner House Books (624 Pirate’s Alley), which faces the rear garden of Saint Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter. Faulkner wrote his first novel, Soldiers' Pay, in the ground-floor rooms that Joe DeSalvo and Rosemary James converted in 1990 into a new- and used-book store as well as a venue for readings and other literary events. The shop offers an especially fine collection of rare books by Southern authors.

Another favorite of New Orleans writers is Garden District Book Shop (2727 Prytania Street), whose readings and signings attract large crowds beneath the exposed rafters of the former nineteenth-century roller-skating rink and mortuary. Readers depend upon recommendations from owner Britton Trice and longtime staffers Ted O’Brien and Amy Loewy when it comes to keeping up with the best new books.

When Tom Lowenburg and Judith Lafitte built Octavia Books (513 Octavia Street) in Uptown New Orleans, they wanted it to be a very cozy setting for author signings, talks, and book-club meetings. They certainly succeeded; something’s always happening there. I have walked in on an Octavia book club discussing my fiction, and I heard David Simon and Eric Overmyer outline the plans for their new HBO series, Treme, in front of a large crowd one night.

Maple Street Book Shop (7529 Maple Street for new books and 7523 Maple Street for used books), founded in 1964 by sisters Mary Kellogg and Rhoda Norman, counted Walker Percy as one of its regulars. In walking distance for Loyola and Tulane students, the converted pink cottage devotes its old kitchen to cookbooks, its parlor to fiction and poetry, and one bedroom to history, another to religion, and a third to children’s literature. A neighboring green cottage is dedicated to used books.

As with all things from the past, New Orleans values its used books. A free list of “The Antiquarian & Second-Hand Bookshops of New Orleans” (with locations, phone numbers, and hours) is available at the sixteen used-book stores listed. Perhaps in keeping with its subject matter, no one has bothered to create an online version of the printed flyer.

Theaters

Theater has flourished in New Orleans since the flood, as discussed in some detail in Christopher Wallenberg’s American Theatre article “In Katrina’s Wake.” But even as exciting new theater companies have appeared, three major facilities have faced crises. Le Petit Théâtre du Vieux Carré (616 Saint Peter Street), the oldest continuously operating community theater in the country, was forced by financial need to sell much of its French Quarter complex to a local restaurant; it hopes to reopen its remaining main stage in the next year. This past summer, Le Chat Noir in the Warehouse District closed its cabaret stage after eleven years, and just last month, Southern Rep lost its lease after over twenty years in Canal Place, on the edge of the French Quarter.

Southern Rep mounted the premiere of my play Rising Water in the spring of 2007, only eighteen months after the flooding of the city. Canal Place had been looted and burned in the chaos that descended upon the city in the aftermath of the levee collapse, and the theater still smelled of smoke on opening night. In the play, a couple is awakened the night after Hurricane Katrina by water as deep as their mattress. Clambering into their attic as the first act opens, they are forced onto the roof at the beginning of the second act when the water continues to rise. The play became the best-selling show in the theater’s history, attracting audiences that stayed in their seats after every performance to tell their own stories about survival and death as they waited for help that didn’t arrive for four sweltering days.

Southern Rep also produced the second play in my trilogy, Shotgun, set a few months after the flood, and it is scheduled to produce the concluding play in 2013, though we have no idea on what stage that production will be mounted.

Fortunately, other facilities are available to New Orleans theater companies. The Anthony Bean Community Theater (1333 South Carrollton Avenue) has served the city’s African American theater community since 2000 through both outstanding productions and a wide-ranging educational program for adults and children, and the Contemporary Arts Center (900 Camp Street) has a frequently used theater space among its galleries.

Saint Claude Avenue has become the center of much of the new theatrical action in New Orleans at such venues as the AllWays Lounge and Theatre (2240 Saint Claude Avenue). And the new Mid-City Theatre (3540 Toulouse Street), in a former warehouse near City Park, is introducing contemporary drama to a new part of town.

Literary Festivals and Reading Series

Each season has its own literary festival in New Orleans. The Tennessee Williams/New Orleans Literary Festival, held March 21 to March 25 this year, will celebrate its twenty-sixth anniversary. Sponsoring poetry, fiction, and one-act play competitions and offering five days of readings, panels, and theatrical presentations, the festival attracts hundreds of book lovers. The Tennessee Williams fest always concludes with a Stanley and Stella Shouting Contest at Jackson Square in which contestants offer their interpretations of Stanley Kowalski’s shout for “STELLAAAAA!” in A Streetcar Named Desire.

Saints and Sinners Literary Festival, founded as an “initiative designed as an innovative way to reach the community with information about HIV/AIDS” and to “bring the GLBT literary community together to celebrate the literary arts,” follows in May with panels, speakers, custom manuscript review sessions, and writing workshops as well as an annual short fiction contest. This year’s festival, to be held May 18 to May 20, will feature a town hall meeting to discuss planning for the 2013 festival, which will mark the organization’s tenth anniversary.

The New Orleans Bookfair celebrated its tenth anniversary this past fall with readings by many local writers, Bill Loehfelm and Mark Yakich among them, and participation by New Orleans publishers such as Baleen Press, Chin Music Press, Lavender Ink, NOLAFugees, Press Street, Garret County, and Trembling Pillow.

Closing the year is Words and Music, a writers conference sponsored by the Pirate’s Alley Faulkner Society, a national arts nonprofit based in New Orleans. With a special focus on international literature, the conference brings together writers, agents, and editors for panels, interviews, and master classes. Established in 1993, its William Faulkner–William Wisdom Creative Writing Competition, with cash awards for the best novel-in-progress, novella, short story, poem, essay, and short story by a high school student, has contributed to the launching of a number of careers—including those of Stewart O’Nan, whose first novel, Snow Angels (Doubleday, 1994), was a competition winner; Julia Glass, who won the National Book Award (NBA) for Three Junes (Pantheon Books, 2002); and Lynn Stegner, who was nominated for the NBA for two novels, Undertow (Baskerville, 1996) and Fata Morgana (Baskerville, 1995).

Throughout the year, various reading series offer a forum for both local writers and visiting authors. One of the most popular is overseen by students from Loyola, Tulane, and the University of New Orleans; 1718: A New Orleans Reading Series, which has featured readers such as novelist and Fairy Tale Review founder Kate Bernheimer and poet Matthea Harvey, is held in the elegant ballroom of the historic Columns Hotel (3811 Saint Charles Avenue), conveniently located on the Saint Charles Avenue streetcar line, usually on the first Tuesday of the month. (Louis Malle shot much of his 1978 film Pretty Baby in the Columns.)

And, of course, local universities such as Loyola, Tulane, Xavier, Dillard, and the University of New Orleans offer readings throughout the year that are free and open to the public.

Media Coverage

Among the casualties of the levee collapse was the book section of the Times-Picayune, the city’s daily newspaper. Susan Larson, the former book editor, now focuses on both writers and readers on The Reading Life, heard weekly on WWNO-FM. Long-time radio anchor Fred Kasten hosts another weekly WWNO program on local writers, The Sound of Books. And WRBH, Reading Radio for the Blind and Print Handicapped, produces the Writers’ Forum with Sherry Lee Alexander and David Benedetto interviewing local and touring writers each week.

The Picayune continues to offer some coverage of books under the direction of Suzanne Stouse, who can be reached at books@timespicayune.com.

Places to Write

Coffee is central to the life of New Orleans. So when a Union blockade prevented the importation of coffee beans into the city during the Civil War, New Orleanians turned to chicory as an expedient. But by the end of hostilities, the taste for chicory had matured into a habit, which persists even a hundred fifty years after the naval blockade that introduced it. The bitter tang of chicory continues to distinguish our coffee from weaker American brews, and coffee shops remain the public reading and writing rooms of the city.

Though the Café du Monde (800 Decatur Street), founded in 1862 just across from Jackson Square in the French Quarter and famed for its beignets and café au laits, is the best-known coffee shop in New Orleans, the bustle of tourists rushing to secure a table makes it too hectic a place to compose literature.

More suitable for serious work is Fair Grinds Coffee House (3133 Ponce de Leon Street). A former bookie joint, Fair Grinds takes its name from the nearby Fair Grounds Race Course & Slots, whose finish line can be seen with binoculars if one stands on a kitchen chair in its backyard. For two years after the levee collapse as the former owners fought with insurers to rebuild the business, regulars brought their Times-Picayunes and thermoses of coffee to gather each Sunday in front of the ruined shop. Community organizer and ACORN founder Wade Rathke purchased the coffeehouse last year. Reopened with free Wi-Fi, a library lamp on each table, and a large covered patio, it is a favorite hangout of writers and musicians.

Nearby, the distinctively triangular CC’s Community Coffee House (2800 Esplanade Avenue) is one of more than thirty locations throughout Louisiana owned by a local coffee importer. With other shops Uptown and in the French Quarter, CC’s is another popular place to read and write.

PJ’s Coffee of New Orleans, also a local chain, is located throughout the region and especially favored by students.

The bars of the city are too numerous to list, but Sherwood Anderson’s brother was a waiter for many years at the Napoleon House (500 Chartres Street). In 1821 the mayor of New Orleans, Nicholas Girod, offered the French Quarter building as a home to the exiled Napoleon, who died before the plot could be executed, but the bar continues to memorialize the French emperor while serving as a congenial meeting place for writers. A wall of doors open on a view of the Louisiana State Supreme Court as well as the former slave exchange across the street. Its interior patio and small dining room offer both food and a quiet spot for conversation.

And just a few blocks away is the recently refurbished Carousel Bar of the luxurious Hotel Monteleone (214 Royal Street), which has been honored as one of only three hotels in the United States designated a literary landmark. Truman Capote insisted that he was born at the Monteleone, and it was home to Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, William Faulkner, and many other writers during their visits to the city. Books by authors who were guests of the French Quarter hotel are displayed in its lobby.

If one can work without coffee or liquor, the Sydney and Walda Besthoff Sculpture Garden at the New Orleans Museum of Art (One Collins C. Diboll Circle, City Park) is a lovely public garden with free admission and a number of shaded nooks where one can read or write. Landscaped with indigenous plants, it boasts over sixty sculptures by artists such as Henry Moore, Louise Bourgeois, Rene Magritte, Fernando Botero, and Isamu Noguchi.

The public libraries of New Orleans offer another quiet place to work. Though my neighborhood branch is still just a trailer nearly seven years after the flood, the Milton H. Latter Memorial Library (5120 Saint Charles Avenue), housed in the beautifully restored 1907 mansion of silent film star Marguerite Clark, is located in the “sliver by the river” that escaped the floodwaters. Rebuilt branch libraries continue to reopen around town; unfortunately, all branches are closed on Fridays because the city can’t afford to keep them open.

***

In 1885, toward the end of his stay in New Orleans, Lafcadio Hearn published Gombo Zhèbes: Little Dictionary of Creole Proverbs. He had gathered those proverbs from six Creole dialects in Louisiana and elsewhere and then translated them into French and English. One is especially resonant today: “Ça ou pédi nen fè ou va trouvé nen sann.” His translation of it reads, “What you lose in the fire, you will find in the ashes.”

Though it was water rather than fire that ravaged the city, there remains much to discover in the ruins we inhabit here. But don’t expect much help from the natives, as hospitable as we may seem, when it comes to unraveling our mysteries. “Divant tranzés faut boutonné canneçon,” explains another Creole proverb. “Before strangers, one must keep one’s drawers buttoned.”