Maybe this will sound melodramatic,” James Frey says, “but since I was fifteen, I never expected to live past the age of twenty-five. I just didn’t think about the future.”

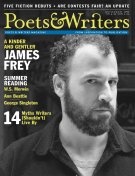

It is a beautiful day outside on Hudson Street, in lower Manhattan, but the thirty-six-year-old author is sitting in a windowless, fourth-floor conference room talking about My Friend Leonard, his second memoir, published in June by Riverhead Books. Relaxed, in camouflage-green pants, a dark cotton sweater, and black-and-white Adidas sandals, Frey crosses his legs and settles into his chair. He does not appear to be the Angry Man portrayed in his books.

As Frey speaks, his voice calm and confident, the fluorescent lights in the room hum. It’s an appropriate soundtrack, given that much of the action of his first memoir, the best-selling A Million Little Pieces (Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2003), takes place under the institutional lights of Hazelden, the renowned Minnesota rehab center where Eric Clapton and actor Matthew Perry have gone to dry out. Frey’s parents—nice, upper-middle-class people who sent him to a nice liberal arts college in his native Ohio—checked their troubled son into Hazelden when he was twenty-three, after more than a decade of drug and alcohol abuse and addiction.

My Friend Leonard takes up where A Million Little Pieces left off, and chronicles a friendship Frey forged while struggling to get clean. Both books are suffused with anger and regret, written by a man who has straddled the line between life and death and has taken his time figuring out which side he wants to jump to. He spares no gory details.

The opening chapter of A Million Little Pieces begins as Frey wakes up on a plane and realizes that four of his teeth are missing, his nose is broken, there is a hole in his cheek, and his eyes are swollen almost shut—the result of a two-week crack binge that ended when he fell face-first to the bottom of an elevator shaft. Written in a rapid-fire, stripped-down style that avoids punctuation and capitalizes “Unit” and “Program” the way Emily Dickinson capitalized “Death” and “Immortality,” Frey’s unflinching account of his physical and spiritual reconstruction—featuring almost every bodily fluid escaping out of almost every orifice—makes other addiction tell-alls seem milquetoast. Or, as Salon.com reviewer Louis Bayard put it, “pussy-ass.”

“The book wasn’t cathartic to write in any way at all,” he says. “It wasn’t meant to be. It wasn’t meant to make me feel better about anything. If anything, it did the opposite—it made me feel worse. I’ve never read it cover to cover, and I probably never will. I don’t have any desire to for a bunch of reasons. I don’t have a desire to relive those experiences. And I think there’s something strange about spending my time reading my own book. There’s something creepy about that.”

Judging by the number of letters Frey gets—immediately following the publication of A Million Little Pieces he received a thousand a week; now the number is down to a hundred, by his estimation—plenty of readers are interested in his experience and eager to meet him and talk about his unconventional recovery. Frey didn’t adopt AA’s twelve-step program, promoted at Hazelden, but instead, turned to a combination of self-reliance, the Tao Te Ching, and the controversial idea that addiction “isn’t a disease” but rather a “choice.” The story told in A Million Little Pieces “has definitely helped people, which has been a very cool part of it, probably the best part,” he says. “It’s always very satisfying and very humbling in a weird way, when somebody comes up to you and says you changed their life.”

A Million Little Pieces garnered critical praise across the board—the New Yorker called it “frenzied, electrifying”—and it received blurbs from film director Gus Van Sant and novelist Bret Easton Ellis. It was a New York Times best-seller and Amazon’s No. 1 title of 2003. There were nationwide book tours for the hardcover and paperback releases, and movie rights were sold. Frey wrote the screenplay. The movie is now in production, slated for a 2006 release.

The buzz is starting again with My Friend Leonard, which tells the story of a friendship Frey made while in rehab. Leonard, a gangster boss who kept him clean in Hazelden throughout A Million Little Pieces, remained a guardian angel in Frey’s post-rehab life, offering him lucrative (and illegal and slightly dangerous) employment. Their gangster-son relationship is the heart of the new book, which follows Frey as he moves from rehab to an Ohio county jail—where he served a brief sentence for hitting a police officer with his car and resisting arrest—to his parents’ birthplace, Chicago, and finally to his life as a Hollywood screenwriter.

The book, which received a starred review from Publishers Weekly, is being touted as even more effective than A Million Little Pieces, perhaps because the action takes place outside the confines of an institution, and explores the universal notions of friendship and love, rather than the addictions of one troubled young man. But My Friend Leonard is written in the same loose, yet crafted style. “It wasn’t hard to get back to writing in that style again,” says Frey, who finished My Friend Leonard in approximately seven months. “I can write the way I write very easily, it comes very naturally,” he says. “But it wasn’t always that way. It took a long time to figure that out.”