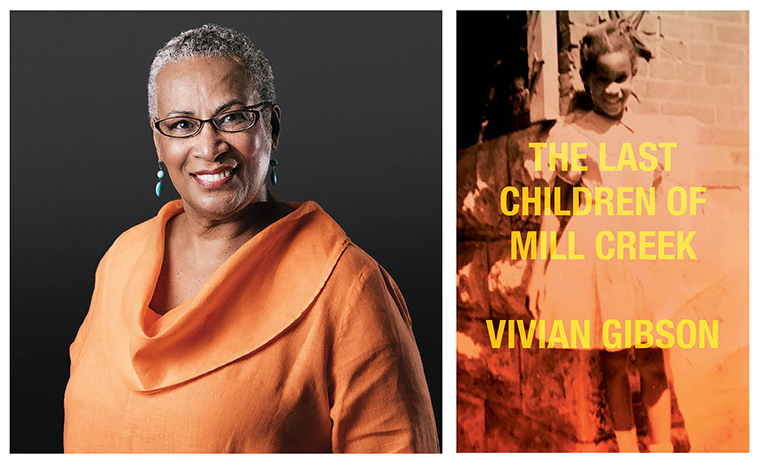

Vivian Gibson, author of The Last Children of Mill Creek, published in April by Belt Publishing. (Credit: Iris Schmidt)

We lived in 800 square feet: three rooms on the first floor of my grandmother’s house, filled mostly with beds. My grandmother, my father’s mother, lived in the rooms above us. There were few words wasted between my mother and her mother-in-law even though we all lived in the same house for years. They were skilled at avoiding each other. It was easy—Mama just had to be in her bedroom at 5:00 a.m. when Grandmama came downstairs to leave for work, and in the kitchen at 5:00 p.m when Grandmama trudged up the stairs after work. I never heard a harsh word or a raised voice between them, but I never saw a smile either. We children were the go-betweens and messengers. Grandmama was referred to by my mother as Miss Hodges—tell Miss Hodges this, take Miss Hodges that. Daddy was the fulcrum on which both women rested—central to their coexistence and function in our household. My grandmother did my father’s laundry weekly and made his lunch every day. I’m sure my mother gladly acquiesced; she had plenty of washing and cooking to do already.

My grandmother joined many of the women on Bernard Street who left home before daylight to catch as many as threestreetcars that transported them to manicured communities just west of the city limits. They arrived early to homes where they cooked and served scrambled eggs for breakfast and readied white children for school. The rest of their day was spent cooking, cleaning, and doing laundry until boarding streetcars in the evening that returned them home just in time to go to bed. Grandmama said that there were sundown laws that mandated people of color to be off the streets in the county by sunset. If she had to work late, her “white folks” (that’s how she referred to her employers) would drive her to the Wellston Loop to catch an eastbound streetcar back into the city.

My grandmother was in bed for the night by 7:30, which was our time to be quiet. A slammed front door, a burst of laughter, or the rhythmic thumps of Sam Cooke singing “Another Saturday night and I ain’t got nobody” on the radio would elicit familiar rapping on her bedroom floor. There was a broomstick leaning against the wall—an arm’s length from her bed—just for the purpose of pounding a signal for silence. Sometimes, out of frustration, she would shuffle in her well-worn slippers to the top of the stairs and call down to my mother, in a commanding tone made no less threatening by her shaky, weary voice: “Frances, make those children be quiet.” It usually worked for the rest of the evening.

Halfway up the stairs that led to Grandmama’s rooms was my favorite retreat from the constant hum made by the ten people inhabiting the three small rooms below. The worn wooden risers and treads of the steps created a perfect work desk for cutting out Betsy McCall paper dolls. The eagerly anticipated monthly issue of McCall’s magazine provided me with hours of cutting out brightly colored paper dresses, coats, and hats that I carefully crimped onto Betsy’s posed body. More hours were spent drawing new outfits of my own design. Using the smooth white cardboard that formed Daddy’s freshly laundered Sunday shirts into a starched folded rectangle, I cut and crafted small easels that held my paper dolls erect for miniature fashion shows.

That space that divided Grandmama’s quiet from our constant hum held another appeal for me—it was an opportunity to eavesdrop on my grandmother’s cloistered existence just feet away. There was always a low murmur from the brown molded-plastic Zenith radio that sat on the crowded table just inside her bedroom door. The black rotary telephone that took up most of the remaining space on the small table rarely rang in the evening. But when it did, I leaned in and pressed the side of my face against the upright wooden balusters and positioned an ear to hear what was said. Sometimes I could tell it was one of the sisters from the church, usually Mother Vine. Mother Vine was a feisty and friendly old lady who always smiled and stroked my face on Sunday mornings when we arrived at the church. She tilted my chin upward and looked me in my eyes in a way that my grandmother never did. She would always ask, “How’s yo’ mama?” as if to distract me while she magically presented a peppermint candy from her purse. I couldn’t see Grandmama’s face, but I could hear a slight smile in her voice after she said, “Hey, Vine.” Their phone conversations never lasted long and ended with a wry, knowing chuckle followed by, “You get some rest now, bye.”

Other times when the phone rang, I would hear a voice and words that I hardly recognized. Her side of the phone conversation started with the usual questioning “Hello?” Then changed to an unfamiliar subservient “Yes, ma’am.” After a pause her voice changed again to a soothing maternal tone that I only heard during these exchanges, “I know,” she’d say reassuringly. “You be a good boy now. Go to bed, and I’ll be there when you wake up in the morning.”

Excerpted from Vivian Gibson’s The Last Children of Mill Creek. Copyright © 2020 by Vivian Gibson. Appears with permission of Belt Publishing.