The stories in our seventh annual feature on debut authors over the age of fifty who published their first books in the past year are narratives of resilience, of persistence, of writing through rejection and loss and, in some cases, through trauma. They are stories of problem-solving, of hard-earned realizations both private and public; stories of small failures, sure, but also stories propelled forward by success. Together they compose a single story of time, of perseverance, of the simple truth that it is never too late to be a writer, to tell your own story, and to share it with the world.

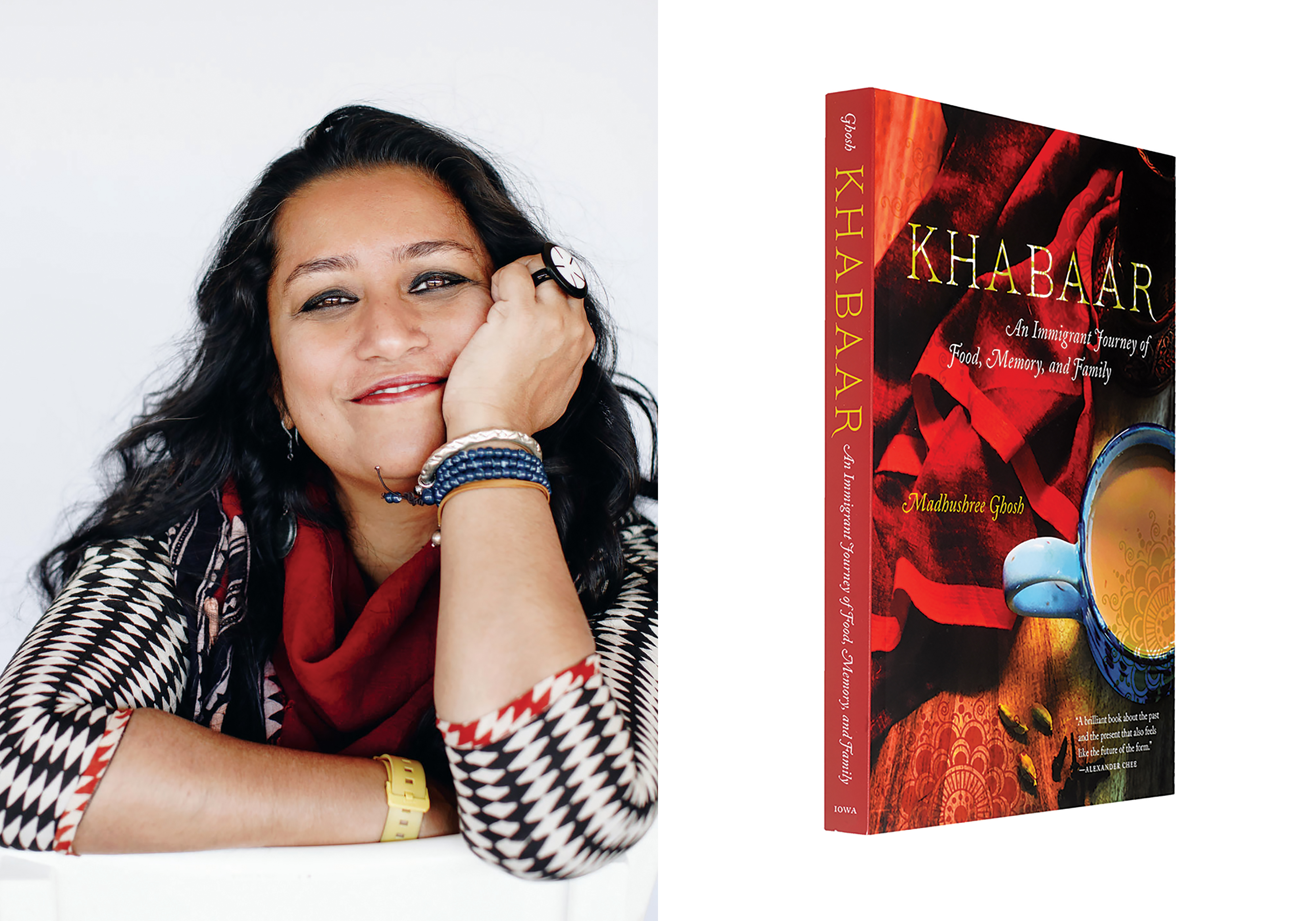

Madhushree Ghosh, author of Khabaar: An Immigrant Journey of Food, Memory, and Family (University of Iowa Press)

Sari Botton, author of And You May Find Yourself: Confessions of a Late-Blooming Gen-X Weirdo (Heliotrope Books)

David Santos Donaldson, author of Greenland (Amistad)

Shareen K. Murayama, author of Housebreak (Bad Betty Press)

Jane Campbell, author of Cat Brushing (Grove Atlantic)

![]()

Madhushree Ghosh

Age: 52. Residence: San Diego, California. Book: Khabaar: An Immigrant Journey of Food, Memory, and Family (University of Iowa Press, April 2022), a food memoir and personal narrative that addresses the question of what it means to belong to one’s country of birth as well as an adopted one, as seen through the lens of the author’s life as a woman of color in science as well as an immigrant daughter of refugees who left an abusive marriage, and braided with the lives of chefs, home cooks, and food-stall owners. Agent: Dana Newman. Editor: Susan Hill Newton.

Dear writer, I wrote a food narrative memoir. I call it this-is-what-you-write-when-you-write-about-things-that-matter. My first physical book is my eighth manuscript. Multiple drafts sit in my Google Drive. But you have those on your own hard drives too, don’t you?

Writing in America for a white readership has been interesting. I started out writing fiction and willingly adapted my natural style of show-and-tell to only show, don’t tell, thereby erasing the folklore and desi storytelling I grew up on. I did it willingly because I wanted to belong; it’s what I felt I needed to do to be seen and heard. Erasure would let the readers know my land and me—this is what I thought was needed.

Writing fiction was a deliberate choice, much like watching the fantastical song-and-dance routines of Bollywood movies. In my writing I wanted to escape my high-stress world of biotech diagnostics. I wanted to create worlds different from mine, but I ended up writing a fictional version of my own. I transferred an unhappy marriage, a weird sense of humor, and immigrant life to my fictional characters. For two decades my practice included writing two hours before my biotech job started and three hours after dinner—a habit I cling to dearly. In 2003 my then-agent took my spectacularly awful first novel to big publishing houses looking for the next great Indian author. “I’d hold on to that job if I were you,” she concluded.

Two decades later I still work in oncology diagnostics. Publishing houses continue to look for the next great South Asian author.

A decade ago my marriage fell apart. My writing stalled. My brain became silent. I switched to nonfiction to make sense of what life was handing to me. I returned to folklore, show and tell—back to my desi roots. I wrote about the marital abuse I experienced. The story of an immigrant daughter of refugees, a woman of color in science—a life of privilege, mixed with discrimination and trauma. Of Ma and Baba’s displaced lives from the British partition of India. Of food as language.

Don’t get me wrong; it’s not like I abandoned fiction for nonfiction—both have a place in my life as a writer. It’s just that to work through life, especially trauma, in my case, I could only explore it and make sense of what was happening through nonfiction/memoir. However, my science brain also guided me to look for connections outside of the personal, in the universal. And what could be more universal than food? The type of cuisine, the availability of certain produce, how and why we cook, what it says when we make a dish a certain way—it all leads to the question of what is comfort, what is home? In corporate/biotech worlds, to place a plate of food in between negotiators is a message that both parties are not only sharing a meal, but also engaging in a discussion to see where they have common ground. In a “foreign” country, eating food that one didn’t grow up with, one navigates to find a similar common ground—what is comforting in that taste, texture, sweetness, or saltiness? Why are we drawn to it, or not?

The lack of, removal of, or access to food is also a story. I realized that when I wrote memoir I naturally gravitated toward what Ma made, what Baba brought home, and how I re-created that in America, knowing the spices, flavors, and ingredients weren’t the same. In doing so I tried to answer the age-old global question: What is home?

Years before the University of Iowa Press asked for Khabaar, fantastic literary magazine editors guided my essays onto their pages. It took two decades to collect the essays that make up Khabaar, and yet it feels like it happened overnight. I focused on writing a good book.

Once I had the manuscript ready, I was connected to my agent, Dana Newman, through another writer friend. Dana did what she does best: She passionately negotiated for me. I focused on writing a book she could sell and didn’t try to do her job or second-guess her. It’s a win-win situation because we are a team. Influenced by Dana’s calming presence in the lead-up to publication, my recommendation to you is that you leave the drama on the page; don’t bring it to your publishing life. The rest is noise.

The obsession with writers’ age seems very Western to me. The need for elastic skin, unwrinkled brows, laugh line–less smiles, especially for women and woman-identifying authors, is perplexing and infuriating. The twenty-five-year-old me would have written a different Khabaar than what a fifty-one-year-old me wrote. Don’t compare oranges with tandoori shrimp. Sometimes a circuitous writing journey happens, and sometimes a standard MFA route is followed. And look, what joy! We create worlds, how lucky are we! Why complicate it with lists, “expiry” dates, and the pressure to look a certain way? Fill yourself with joy that you get to write magic.

I can’t wait to read your work. Go, write it, will you?