Throughout his long career, Philip Levine has established a reputation for poems honoring the working class, beginning with the people he encountered as a young man laboring in the factories of Detroit. Though he has taught in writing programs nationwide since the 1950s, his poetry has maintained a stronger identification with the autoworker than the academic. He has consistently addressed themes of alienation and oppression, yet his body of work shows a poetry changing with the man.

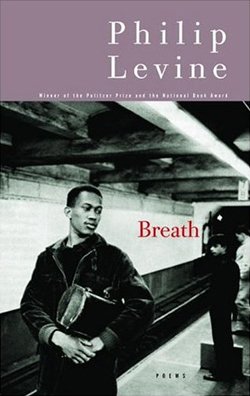

Levine has published seventeen collections of poems, most recently Breath (Knopf, 2004), as well as essays, interviews, and translations; a bilingual edition of Tarumba: The Selected Poems of Jaime Sabines (translated and edited with Ernesto Trejo) was released in paperback by Sarabande Books last year. He has earned numerous honors, including the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, and two Guggenheim Foundation fellowships, and is currently the Distinguished Poet-in-Residence at NYU.

Last November, at a public celebration that filled Cooper Union’s 900-seat Great Hall, a dozen poets read poems and told stories commemorating Levine’s contribution to American letters. In January, Levine turned eighty.

Poets & Writers Magazine asked him how his writing is going these days.

Philip Levine: Well, it’s not going the way it used to. I lack the pure energy that I once had. On the other hand, I have great patience. I think my greatest weakness as a young writer was impatience. Now I’m very patient, which is ironic because I don’t have all the time in the world. Last summer I wrote quite a bit, and at the age of fifty I would’ve kept going and kept going, but I knew at one point I wasn’t getting anything worth getting. It was time to stop.

P&W: How do you see your poetry as having evolved over time?

PL: Well, you know, at that eightieth-birthday thing, Eddie Hirsch made an interesting remark. He was reading a poem, “To Cipriano, in the Wind.” Eddie started talking about Spanish anarchism and how much it had meant to me, and then he realized if he were complete he’d be there forever, so he just said, “It took him from rage to elegy to celebration.” It’s a kind of simplification, but it’s not inaccurate when I look back at the work. What I see more than anything is a technical shifting: I began as a free-verse poet and in my early twenties began writing formal poems. My first book, which I published when I was thirty-five, is largely formal. Why? Because the poets I was reading were formal poets. And if somebody had said to me, “Who's the greatest lyric poet in the English language?” when I was twenty-five, I would have said William Blake. The funny thing is I would say the same thing today. I think he’s just phenomenal. Phenomenal—technically breathtaking, his insights are awesome. He just keeps giving you things you can live by.

P&W: You once joked, “We all know what a Levine poem is: ‘I go to work in the factory, I go home…’”

PL: Well, I don’t think there’s such a poem in my last book. I don’t think there’s one. But I still think people who read a lot of poetry would recognize my poems.

P&W: They’d recognize the voice?

PL: Yeah, that’s right.

P&W: What else?

PL: The characters themselves: who they are, what class they come from. I mean, you’re never going to pick up a poem of mine (unless it’s a comic poem) about wine mavens, right? Or real estate agents, you know, or CEOs. They’re going to be autoworkers, or they’re going to be guys working on a construction site or women complaining about how the grease eats into their hands because of the jobs they do. So there’s this whole social class I think that you would recognize, of the characters who move through my poems. As far as landscape goes, there’s New York now, there’s Detroit, there’s California, there’s Spain—the places that I’ve lived. There’s even North Carolina; I lived there for a while. I guess my poems have particular rhythmic structures. There used to be the notion that I wrote in a slender line. And I even have a poem in which I have fun with that.

P&W: The poem about your cat Nellie, “A Theory of Prosody.”

PL: Yeah. “A Theory of Prosody” was about the cat line, that narrow line. And people would say, “Why do you write in that line?” And I would say, “Well, The New Yorker pays by the line!” But that had nothing to do with it. What it had to do with was my total entrancement with Yeats’s trimeter line and an effort to convert some of that energy that he could get in long passages into free verse. I wanted to write something that moved with the beauty and force of “Easter 1916”: I thought, “You can’t write a form more beautiful than this. This is so gorgeous.” And when you want it to be epigrammatic, you can hold the lines up and make the rhymes consistent, when you want it narrative you can let it overflow—it’s just such a supple, wonderful form. I had tried to do it in rhyme, in metrical poems, earlier, but now I was trying to do it in free verse. I just loved doing it, when I could do it right. You know, which certainly wasn’t always.

P&W: When you look at other poets’ bodies of work, do you admire steady, recognizable poets or somebody like Roethke, who you could say reinvented himself with each book?

PL: Oh, I’m much more taken with someone like Roethke, with the willingness to voyage out into a new voice, to voyage out into a new structure, to voyage out into even new material, to write those beautifully formed metrical poems and then go to the free-verse poems, the greenhouse poems, then go to those mad poems like “The Lost Son” and then go back to a Yeatsian structure, and then finally wind up with a kind of Whitmanian poem—this to me is breathtaking. The poet I see of late who’s doing something like this is Louise Glück. I’m full of admiration for her willingness to leave a style she’s mastered—a voice and style so many young poets admire and imitate—for this new thing, and I take my hat off to her. These new poems of hers are wonderful.

P&W: By the way, do you still feel that Whitman’s the greatest American poet?

PL: Oh, yeah. I don’t think anybody else comes close. He has a vision of not only what America might be but what a human being—a man or a woman—might be. And our relationship to the earth and our relationship to each other and our relationship to other creatures—I think it’s all there in Whitman. I mean, Emily Dickinson’s a fabulous poet, but you don’t find that kind of vision there. The vision that I do find I often don’t like. Sometimes she sounds so persecuted by her own notion of what God is. Whereas the creator in Whitman is this incredible force that gave us all the gift of our bodies and our spirits—yeah, I’ll take Whitman any day.

P&W: Whitman revised and republished Leaves of Grass for decades. Your friend and colleague Galway Kinnell has revised many previously collected poems for later collections. I wonder if you’ve ever had the impulse.

PL: Yes, but by and large I resisted. I did revise the poem “1933,” which appeared in the book 1933, when my Selected Poems came; I had never been satisfied with the poem, and I thought, I’ll rewrite it, and everyone will admire the new version. No one noticed! But that isn’t the reason that I don’t revise much after a poem appears in a collection. I think the reason came earlier: I knew a man who was writing accomplished but not very good poems when we were both about twenty-five or -six, and he published a book when he was in his early thirties, and then some years later he published the same book again, rewritten. He was now like forty-something. These are the same poems he was working on at twenty-five, and I thought, “There’s a lesson for you. Just keep fucking with the same poems and making them better or worse or who knows what.” He didn’t make them better. Meanwhile, of course, there was nothing new coming. Then finally I did see a new book by him, and it was so wretched I thought, “Well maybe he was right: go back and rewrite those old poems!”

P&W: What’s a Levine poem now?

PL: I have no idea. I certainly don’t have any idea what the next one will be. I’ve been writing a lot of prose poems. And I probably have a dozen I can live with. Many of them are comic; there are several that are serious. The first one I ever wrote was in Amsterdam. It was a long time ago, I would say thirty years ago. My wife had gone off with a friend, and my kids had gone off to get stoned, and I had time. There was a park named Vondelpark, named after a poet, and I went there. I’m a guy who writes a lot. I enjoy writing; I feel I should be writing, keep my hand in it. So I started writing something, and I wrote a little piece about a Dutch doctor that I knew and loved. And it was the first good prose poem I ever wrote. And then I wrote a couple more, and they weren’t any good (I published them, but they stunk). And then about six or seven years ago, I wrote a bunch, and I didn’t do anything with them. And then one day a friend asked me if I had any prose poems—he wanted to publish them—and I went back and looked at those poems, and I could see that each one had a kind of germ in it, and so I began rewriting them, and then I got the idea for more, still more… And they were great fun to write, but I’m going go back to verse now.