My first time? November 29, 1984. It was the third story I’d ever written and, like the other two, was brooding and mannered and obscure, the work of a young writer writing the way he thought writers wrote. I was confident about that story, though. At six pages, it was the longest one I’d ever written, capacious by my standards, the perfect story to send to the best magazine in the world. I had a pretty good feeling that the New Yorker was going to buy it, publish it, and I was going to be on my way. I was twenty-five years old.

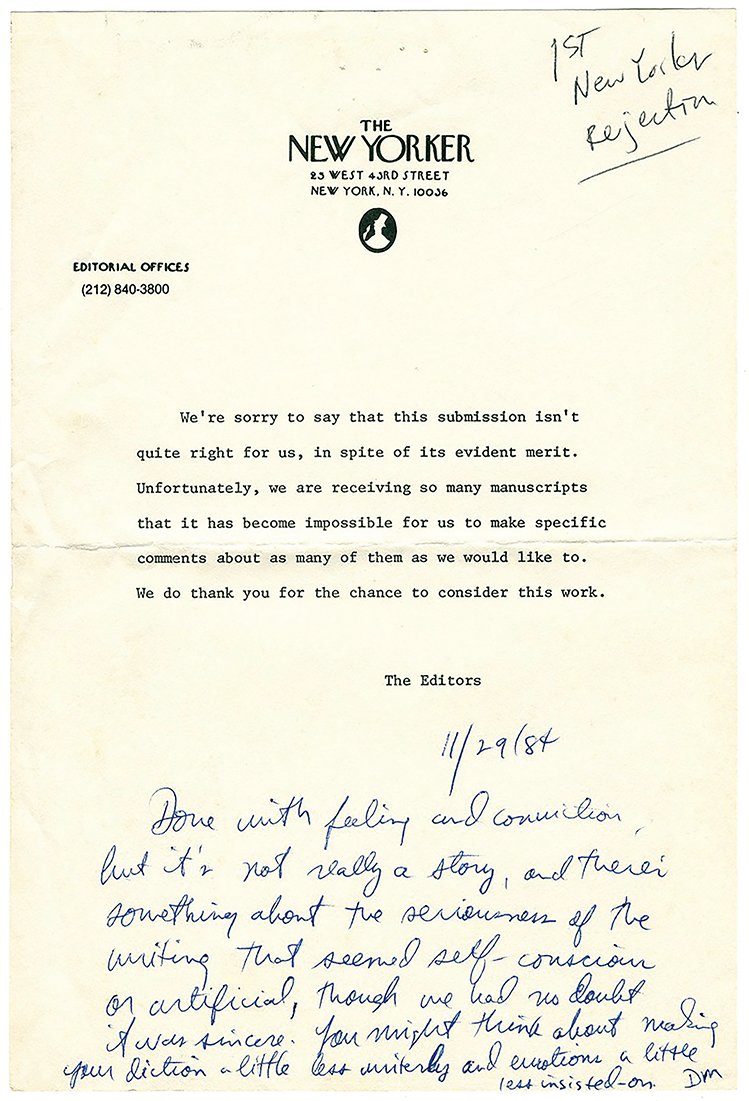

The author’s first rejection slip from the New Yorker’s Daniel Menaker.

Before I say what I’m about to say I need to say this: I’m a lucky writer. I’ve published six novels, most recently Extraordinary Adventures, which was released this past May. Big Fish, my first novel, was a New York Times best-seller and was adapted into a Tim Burton film and then a Broadway musical, and my other books have been published to “critical acclaim”—which means they didn’t sell as well as the first one. My books have taken me all over the world; I’ve had a wonderful time, and I hold not even the smallest grudge toward anybody.

However.

Of all the things I’ve wanted to happen in my writing life, the one I’ve wanted longer than any other is to have one of my short stories published in the New Yorker. I have been trying to do that, without success, for over thirty years.

For that first decade of my writing life, no single thing more closely corresponded to my idea of success than getting into the New Yorker. The writers who had influenced me the most—Salinger, Updike, Cheever, Nabokov, Welty—had been published there. It was more than a magazine to me: It was where the literature of the twentieth century actually happened. To be accepted by the New Yorker and edited by the great literary gatekeepers of this country—the heirs of William Shawn and William Maxwell—would be an honor and a validation that could not be equaled.

How many stories did I submit? I don’t really know. But I’d say that over the course of the last thirty-four years I’ve sent that magazine fifty stories. It may be more. I’m not sure because I kept only some of the rejection slips. The good ones, as writers call them, I kept some of those.

Somehow most of my early stories had the good fortune to land on the editorial desk of a guy named Daniel Menaker. I had no idea who this person was, and it didn’t really matter because at that time in my life, editors were all-powerful demigods whose approval would allow me entry into the world I hungrily watched from afar, typing in solitude in my tiny duplex in Carrboro, North Carolina. Daniel Menaker and I became pen pals: Year after year I wrote stories, sent them to him, and he slipped them into the self-addressed stamped envelope and sent them back to me.

But not just that. He would always take a moment to write a little something, and sign it “DM.”

Looking at the first rejection letter I received from him brings back memories of the young me, the me who really knew nothing at all about what he was doing, the me who may as well have been panning for gold in the bathtub. I have many more notes like this in my collection, spanning over a decade. The last note Menaker sent, dated August 9, 1990, is actually a letter typed on New Yorker stationery, without the normal boilerplate. It says, among other things, that the story I submitted was “very good…as far as it goes.” Which apparently wasn’t very far, but he ends it by saying something truly lovely and that moved me when I read it. “I know we’ve been seeing your work for some time now,” he wrote, “but we’d be glad to see more.”

He remembered me, out of all the writers he read, and made note of my decade-long struggle. Recently I was showing my collection of rejections to a student who was going through a spate of his own, and I thought, “Twenty-five years have passed since Daniel Menaker wrote that note. I wonder if he remembers me still.” Impossible.

***

I am happy to meet with Daniel Wallace anytime,” Menaker wrote to my agent, who had contacted him on my behalf. “I do remember my exchanges with him, and I do remember thinking again and again that he had a lot of talent and hoping that we would end up using something of his.”

Since our epistolary relationship began in 1984, I’d learned a lot about Daniel Menaker. He was an editor at the New Yorker for twenty years, an award-winning writer who has published a half dozen books: novels, story collections, a memoir. His stories, many of them published in the magazine, had won O. Henry Awards. After leaving the New Yorker he became an executive editor at Random House and, later, editor in chief. Now he’s an associate professor at the Stony Brook MFA program and writing his novels. The list of great writers he worked with in his career as a magazine and book editor, from Isaac Bashevis Singer and Alice Munro to Elizabeth Strout and George Saunders, is unmatched. Take a look at his website. It’s astonishing.

We made a date to meet this past December at a café on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Other than a waitress, the café was empty when I got there. I took the table farthest from the door, and when he came in I waved, because even though I’d never seen him before this could not have been anybody else. He wore a herringbone jacket, slightly rumpled chinos, a dark blue V-neck sweater over a button-down shirt. His hair was snowy white, short but curly and thick, and his beardish goatee was an ashy gray. Eyes sharp and clear and playful.

We did not have long, only an hour, so I thought I should get right to talking about the New Yorker and, you know, me. But we didn’t. We talked about ants for a while. Are they really all that smart? Yes and no, we decided. We talked about dogs. Then we talked about our wives and whether we would die before they did (probably). We talked about TV and movies and Hollywood agents. He ordered waffles and they were small and delicate and he offered me one and I ate it.

Daniel Menaker shared his waffles with me.

Time passed like this. After a while he nodded toward my pen and my reporter’s notebook, woefully blank. “So did you want to ask me any questions?”

That was, after all, why I was there. But I didn’t want to ask him any questions because I was enjoying our conversation; he was too, I thought. It was as if we were old friends, as if we had known each other for years—and in a way I guess we had.

But I asked him a few questions, and he gave me a few answers. He told me he wrote personal notes on about one out of every forty stories he read; that he “looked” at almost a hundred stories every week and that he himself had been rejected by the New Yorker many times, even while he worked there. And he told me two or three inside stories that he made me promise not to write about, but believe me, they’re great stories and I wish I hadn’t promised.

Such a good, gentle, honest man, this Daniel Menaker. Did he realize just how much power he had to change a writer’s life? Did he think about it when he was reading a story by a writer (me, for instance) who had never been published there and what that would mean if he were?

He thought about my question. “Yes and no,” he said. (He equivocated like this a lot. Yes and no. Maybe, maybe not. It is and it isn’t.) But his first commitment was to the story and to nothing else. This is something he had learned at the elbow of William Maxwell, who had edited Cheever, Salinger, and Updike. He inherited Maxwell’s point of view: He wasn’t really working for the magazine; he was working for the writer.

At the same time, he was aware that a writer who publishes a story in the New Yorker is given unprecedented and unmatched validation. She might get a book contract, and that story—that one story—might open doors for her for years to come.

“So yes,” he said. “Yes and no.”

Then, waffles done, tea cooling, he asked me a question. “Do you still submit?” I nodded. There is someone at the magazine now doing for me exactly what Daniel Menaker did all those years ago, now via e-mail: You have an admirably clean, inviting prose style…it’s a very good story, but….

It’s the but I have lived with for thirty years.

So, no, the New Yorker did not change my life, but somehow the life I ended up with turned out to be pretty great. I mean, here I was eating Daniel Menaker’s waffles at a small café in New York City, talking about ants and dogs and death. He said we should go out to dinner the next time I was in the city, and though I haven’t been back yet, we’re still in touch. Do you see what just happened? After a lifetime of rejection, I had been accepted. I had made a friend.

A writer’s work is often produced in a room, alone, and when we think the work is as good as we can make it, we send it out into the world as a kind of emissary, even a facsimile of our actual selves. We send it to an editor. An editor isn’t really a human being, though, not to a young writer; he’s more like a judge, etheric, a gatekeeper with powers we can only dream about. This is the mistake we often make and why rejection can be so daunting. Maybe what we need is a revolutionary change in the submission process: If we could all just eat waffles with our would-be editors, the writer’s world would be a better place.

Daniel Wallace is the J. Ross MacDonald Distinguished Professor of English at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, where he directs the creative writing program. He is the author of six novels, including Big Fish (Algonquin Books, 1998) and, most recently, Extraordinary Adventures (St. Martin’s Press, 2017).