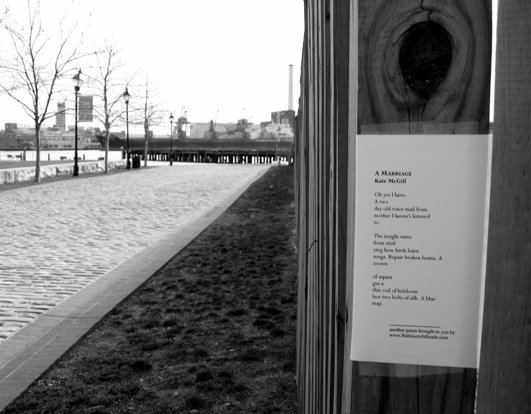

Bits of verse taped to lampposts and boarded-up buildings have become a common sight in Baltimore thanks to Adam Robinson, who founded the outdoor poetry journal Is Reads three years ago. "The concept is to put poems in places where people normally don't think about literature—or poetry, specifically—and would never encounter it," says Robinson, who twice a year prints about a dozen poems on high-quality white paper, cuts them to size, and posts them on telephone poles, brick walls, office bulletin boards—even the rotting plywood used to board up empty buildings, a leitmotif in some of Baltimore's economically depressed neighborhoods.

Robinson started Baltimore Is Reads in 2006, along with two other writers, to fulfill an assignment for a graduate seminar at the University of Baltimore that required him to expand the idea of what a book is. At the time, Robinson was inspired by the anonymous panel paintings that are often hung on abandoned buildings in some areas of the city, and by Baltimore's motto: "The city that reads." In fact, the city suffers from one of the highest illiteracy rates in the nation; according to the U.S. Census Bureau, fully one-quarter of its population hasn't finished high school.

Last year Robinson expanded Is Reads to public spaces in Nashville, having joined forces with Peter Cole, publisher and editor of Keyhole, an independent press and literary magazine based in the Tennessee capital. "It's editing in a way that I never thought was possible," says Cole, who contacted Robinson last August about starting Nashville Is Reads after he discovered the project online at www.isreads.com. "I found the Web site, and I just thought it was a cool idea. I wished I'd thought of it." The two have since made plans to launch Is Reads in other cities, including Minneapolis, Saint Paul, and Pittsburgh. Those who want to participate can contact the editors, who will send PDF files of the journal's contents along with instructions explaining what to do. [Editor's note: It's not a bad idea to make sure there isn’t a local ordinance prohibiting such posting.]

Robinson solicits work for Is Reads, but anyone can submit poems via e-mail for consideration. Typical contributions are experimental, sometimes playful fragments of quotidian existence. Randy Russell's poem "Sunday," for example, is a staccato ode to diners (with the opening lines: "TOM ATO KETCH UP / POUR ABLE MUS TARD / SUPE RIOR COF FEE") and Lauren Bender's "This Morning" is a sad reverie about "grandmom," "some kind of kind of taxidermied finch," and death. Baltimore poets like Bender feature prominently, but the eclectic list of contributors includes Towondo "Beyababa" Clayborn, founder of the experimental hip-hop group Occasional Detroit, who contributed a rhythmic ditty about snow; Kendra Grant Malone, a young filmmaker and blogger in Brooklyn, New York, whose frantic love letter was published in the third issue; and Bryanna Moran, whose inventive poem and drawing reveals her single-digit age.

The publishing-and-distribution process of Is Reads involves a printer, tape, and a couple of people willing to wander around town. It's a refreshing approach to putting out a journal, but it nonetheless recalls historic forms such as broadsheets and political posters. Justin Sirois, an Is Reads contributor and founder of the Baltimore-based experimental writing and publishing collective Narrow House, describes the journal as "a guerrilla-style public literature broadside initiative. It's an attempt to alter the urban environment with language that would never otherwise have a chance to engage the public. It's a little out of place, but that's the hook."

Cole and Robinson each have their own preferences for where to post poems that are as much a commentary on the cities in which they live as any overarching editorial principles. Robinson likes to tape up poems in high-traffic areas of Baltimore, while Cole prefers to post them—under the cover of darkness—at the end of long, lonely alleys in Nashville. It's not uncommon for the contents of Nashville Is Reads to hang alongside posters promoting musical acts. "Nashville is a music city. We have thirty bands playing every day. I don't think you can find a telephone pole in Nashville that's not pasted with band flyers," says Cole. Meanwhile, in Baltimore, Robinson uses Scotch tape to secure the poems "so they're totally impermanent," he says. "I like the idea of doing really valuable things and having it just thrown away."

Through the simple act of hanging poems, the outdoor poetry journal encourages a new outlook for those wandering through a sometimes-mundane urban existence. The Web site features the text of poems and a map pinpointing their location, as well as photos of the work in its new environment.

Contributor Mairéad Byrne says she considers Is Reads a vehicle for carrying on the long tradition of poets' directly addressing a city—for example, William Carlos Williams in Paterson, Walt Whitman in "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry," Hart Crane in The Bridge, and Federico García Lorca in A Poet in New York. "I think Langston Hughes's first poem was to his high school," Byrne says. "It makes sense to me. It's natural to write to a city—and post what you write in a public place. You can be sure it will be read."

Not everyone shares Byrne's optimism, however. In fact, no one involved in the making of Is Reads is able to weigh public response to the project at all; it's nearly impossible to identify who is reading the poems or what they might think of them. "I haven't seen a single person reading them," admits Cole. Sirois hasn't received any feedback either: "I'm not sure if the project means anything to the city; it's impossible to gauge. Maybe that's fine though."

"I don't expect that by doing this I'm going to change anybody's life," says Robinson. "But for the ten seconds people stand in front of it, I hope they just kind of wonder about poetry again."

Kiki Anderson is a poet, translator, and arts and culture writer. She writes about music at theheretohear.blogspot.com.

Comments

mairead replied on Permalink

Baltimore Is Reads as a Living Metaphor for Poetry Publication