This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Aurora Mattia, whose debut novel, The Fifth Wound, is out now from Nightboat Books. In this surreal autofictional tale, readers encounter multiple narratives: a fraught romantic friendship between Aurora and Ezekiel, a harrowing recollection of transphobic abuse and trauma, and a wild interior landscape of dreams and fantasies. The book also offers a critique of the literary industry, as narrator Aurora struggles to gain acceptance for her thematically and stylistically radical writing. Text-message conversations, photographs, and quotations are interspersed with prose that swerves between diaristic confession and more traditional narrative embedded with footnote-like asides. “This is a book of doors. This is a book of tunnels. This is a switchboard. It is for passing through. For conjuring dimensions,” Mattia writes. Publishers Weekly calls The Fifth Wound “a fierce debut.... Lovers of experimental fiction will find what they’re looking for.” Aurora Mattia was born in Hong Kong and lives in Brooklyn. Her writing has appeared in Zoetrope: All-Story, the Renaissance Society’s exhibition Nine Lives, and in RISD Museum’s exhibition any distance between us, on view last year.

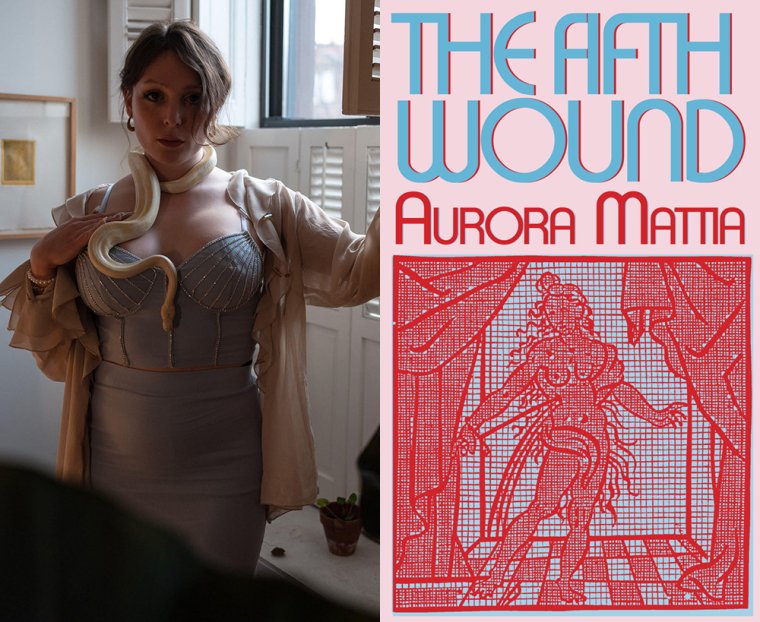

Aurora Mattia, author of The Fifth Wound. (Credit: Elle Pérez)

1. How long did it take you to write The Fifth Wound?

I wrote it as I lived it. So I wrote for a month then didn’t write for two months, then again for three months and then not for eight months, then again for four more months, and then it was done. I wrote and lived, wrote and lived, like inhaling and exhaling.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Realizing that the book was, in its first draft—insofar as my romance with Ezekiel was concerned—recapitulating the form of the victim and the criminal, of which form I was writing the book, on a structural scale, as a refusal. A refusal that was the elaboration of my refusal of the police report the cops attempted to extract from me, minutes after I was knifed in the face on the subway. I wanted the book to be the elaboration of that refusal.

What began as a personal howl became an interpersonal prayer. I realized, as I kept writing, as I chased after whatever felt most intense—whatever made me feel embodied, or at least whatever could replace embodiment—I mean as the consequences of my recklessness, my impulsiveness, my implosive impulse to live “for the story of it,” began to emerge and recontextualize the past, how my premises, the rules by which I lived, were harming the people who loved me and cared for me most, I mean how I was harming those people by living my life as an open door. Dreams passed through that door, and also the traumas I was refusing to face, turning my head aside as they passed through me, reaching for the people I loved.

As I began to live not for an abstracted ideal of paradisal relation, but to take responsibility for the immense responsibility of love, which is a lifelong labor but a labor always for the present, I began to write with more awareness of the holiness of the people in my life, how much I was taking for granted the constancy of Noel and Velvet’s exertions of love, and the entangled and painful spirals—moments of intense nearness, arcs and curves of distance—of the double helix by which Ezekiel and I expressed our relationship, not as victim and villain, but as two fairies grasping in the dark, through time, two fairies enclosed in the terrible envelopes of our own reverberating halos, sacred and burning. The only ways we knew how to love one another were also ways of hurting each other. Realizing that I was capable of hurting Ezekiel destabilized my understanding of the story of my life—and destabilized the story of the book. Comprehending the ways I had hurt Noel and Velvet and Ezekiel—in addition to all the implications that had in my personal life, how I live my everyday, how I love, I also had to integrate that reality into my fantasies, the fantasies by which I try to create something other than the world as it is.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

When a phrase comes to me, I text it to myself. Otherwise I write when the world is quiet, usually early in the morning. Sometimes by hand in a big, flat notebook, my soulstorm on the left and my sentences on the right; other times I write on a laptop, bent over like a nun with her prayer book. I write when I want to say something to someone in particular—but can’t. So I spill across the pages, like pearls falling in a field of snow.

4. What are you reading right now?

Joan Didion, Play It as It Lays and Democracy. Fanny Howe, Holy Smoke and Night Philosophy. Camonghne Felix, Dyscalculia: A Love Story of Epic Miscalculation. Judith Schalansky, An Inventory of Losses. Magda Cârneci, FEM.

5. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of The Fifth Wound?

As I rewrote older passages, the primordial layer of lamentation was, like a sand castle, softened by waves of reflection, from which the ruin of an interpersonal epoch emerged, in nearer resemblance to nature: more formless and somehow more vulnerable; but more mysterious, too, like accidentally seeing the soul of something; and reaching, as ruins do, for the wings of angels.

6. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

After two years of silence, Ezekiel followed me on Instagram. I messaged him asking why. We exchanged a few more messages and agreed to have a phone call. He called three months later. In the time between the message and the call, I began writing. Because I was thinking about him again, in my bed, recovering from the knifing and from having my tits done. The first line I wrote:

“I worry who will read these pages, because I am no longer the author of private letters for one man...”

The first epigraphs I collected:

“Come on baby, come on darling—

Let me steal this moment from you now:

Come on angel,

come on come on darling—

Let’s exchange the experience.”

—Kate Bush, “Running Up That Hill”

“The wolf howled under the leaves

And spit out the prettiest feathers

Of his meal of fowl:

Like him I consume myself.”

—Arthur Rimbaud, A Season in Hell

“...for she sits in a green field

and warbles you to death with the sweetness of her song.”

—Homer, The Odyssey

And in the middle of the text:

“The woman wondered, absorbed, whether there might not be a thousand other things that had happened to her, and which she had simply not learned about yet. She wondered, with the gravity of a discovery, whether she had not really chosen to live off a few past facts, when she could live off others ... Here was the past revealing itself to be as full of possibilities as the future. Because the past has the richness of what has already happened.” —Clarice Lispector, The Apple in the Dark

None of these became epigraphs in the end, but they give glimpses, like a dense seed of topaz, of the “pre-existence” of the book.

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Fifth Wound, what would you say?

Live for the people you love, and for your and their own inviolable mysteries. Forget the story, find the instant. Avoid psych wards at all costs.

8. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Make and sell porn, study Middle English, translate Classical Chinese, fall in and out of love.

9. Which artists have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Clarice Lispector was first and foremost. I read Água Viva on my nineteenth birthday in Shanghai, realizing, again, with a repercussive shock, that I was a woman and a writer, and that, for me, those two facts were inseparable. I would write myself into womanhood. I would perfume the pages. I read every one of her novels and stories.

But, thinking chronologically, my mother, my older sibling CJ, Avril Lavigne, Hank Williams, Townes Van Zandt, Leonard Cohen, Joanna Newsom, Kate Bush, Emmylou Harris, Santigold, Beach House, Hole, Lucinda Williams, FKA Twigs, Gillian Welch, Bong Joon Ho (The Host and Okja), Charlie Kaufman (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Adaptation), Chen Kaige (Farewell My Concubine), Wong Kar-wai (Chungking Express, Fallen Angels, and Happy Together), Brit Marling & Zal Batmanglij (The OA), The Cave, Final Destination, The Matrix, Buddha Mountain, Sunshine, Y Tu Mamá También, Amores Perros, Interstellar, Arrival, Point Break, Vanilla Sky, It Follows, Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), Jennifer’s Body, The Thing, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Antichrist, Contact, Cy Twombly, Antoni Gaudí (La Sagrada Familia), Hugh Steers, Toni Morrison (Sula), the Gospel of John, Liu Xiyi (代悲白头翁), Jorge Luis Borges (Collected Fictions), Fernando Pessoa (The Book of Disquiet), Virginia Woolf (The Waves, Mrs. Dalloway, Jacob’s Room, and To The Lighthouse), Donald Barthelme (Forty Stories), Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (Dictée and Temps Morts), Laszlo Krasznahorkai (War & War), Hilda Hilst (The Obscene Madame D), Evelyn Waugh (A Handful of Dust), Susan Howe (Souls of the Labadie Tract), Machado De Assis (The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas), Nikolai Gogol (“Diary of a Madman”), Thomas Bernhard (Concrete and The Loser), Fyodor Dostoevsky (Notes from Underground, Crime & Punishment), Leo Tolstoy (Anna Karenina), Gabriel García Márquez (One Hundred Years of Solitude), Cao Xueqin (Dream of the Red Chamber, Vol. 1), William Faulkner (Absalom, Absalom! and The Sound and the Fury), Italo Calvino (If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler), Sei Shōnagon (The Pillow Book), José Donoso (The Obscene Bird of Night and Hell Has No Limits), Severo Sarduy (Cobra and From Cuba With a Song), certain passages in the first two volumes of Proust, Manuel Puig (Kiss of the Spider Woman), the first hundred pages of Ulysses, (which is as much as I’ve read at this point), John Keene (Counternarratives), Édouard Glissant (Poetics of Relation), Rachel Rabbit White (Porn Carnival), Emily Dickinson (Collected Poems), James Baldwin (Another Country), Chelsey Minnis (Bad Bad), Maurice Blanchot (The Gaze of Orpheus and Other Literary Essays), Juliana Huxtable (Mucus in My Pineal Gland), and Fanny Howe (Dump Gull).

When I was thirteen, after reading The Giver, I wrote an email to Lois Lowry, telling her I was gay and lonely and loved her book. And she wrote me back.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

“I write on the line between truth and bad taste. And it is a thin line.” That’s from one of Clarice Lispector’s crônicas.