This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Danez Smith, whose third poetry collection, Homie, is out today from Graywolf Press. Homie is a tribute to friendships of many forms. There are two young Black boys on bikes who swerve, “friend-drunk, making their little loops, sun-lotioned // faces screwed up with that first & cleanest love / we forget to name as such.” There is kinship across generations—the lineage extended from Smith to their mother, grandmother, and on. There is love for the dead. And even here, in the face of the most gut-wrenching loss and violence, Smith takes heart: A friend becomes the dust in the room, on the fan, in the ear. “The wind is tangled / with the dust of dead homies,” Smith writes. With Homie, they model a vulnerability and tenderness that allows for a full self to emerge, allowing and inviting others to join it. “The world doesn’t deserve this book—this fierce abundance, this indomitable tender—but we need it, desperately,” writes Franny Choi. “Their virtuosic abilities are matched by the ambitousness of the heart.” Danez Smith is the author of two previous collections, Don’t Call Us Dead (Graywolf Press, 2017), a National Book Award finalist and winner of the Forward Prize for Best Collection, and [insert] boy (YesYes Books, 2014), winner of the Kate Tufts Discovery Award and the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Poetry. They are the recipient of fellowships from Poetry Foundation, Cave Canem, and the National Endowment for the Arts. They are also a member of the Dark Noise Collective and co-host VS, a podcast sponsored by the Poetry Foundation and Postloudness.

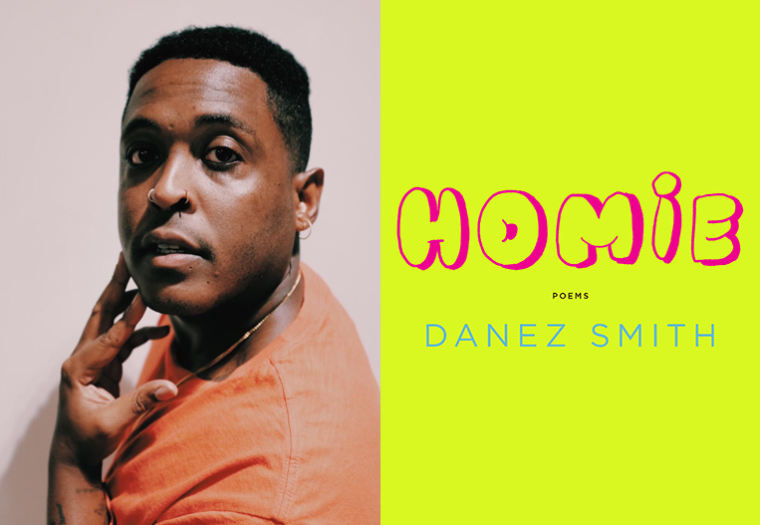

Danez Smith, author of Homie. (Credit: Tabia Yapp)

1. How long did it take you to write Homie?

The earliest version of the oldest poem in Homie/My Nig was written in 2014, but I didn’t know I was writing this book then. The book didn’t announce itself to me until 2017, when I went looking for it. I scanned over the poems I had been writing, scanning to see what my brain had been up to without me noticing and there was a thicc thread of friendship and intimacy I had been quietly thinking into. From there, the book began to be a book and not just poems written out of urgency and curiosity.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Allowing myself to gush and love and stomp joy while avoiding corniness. Allowing myself to be corny. Embracing sentimentality—who doesn’t want abundant tenderness? Allowing myself to revel in a different voice than my previous collections. Allowing myself to hate the book sometimes and make that frustration useful instead of hindering.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Wherever I have to: I like my dining room table and airplanes a lot. Whenever I have to: lately I enjoy the haze of late nights or the loopy brain-state post-workout. However it gets done: I try to do first drafts or quick notes either by hand or in the Notes app, I edit better once I’ve transferred it to a Word document.

4. What are you reading right now?

How to Break Up With Your Phone by Catherine Price. LOVED Rick Barot’s forthcoming The Galleons; it was invigorating to see a master poet push further and further into the strange unknown of their relationship with language, all the while the poems being full of intelligence and heart. Sitting next to Tomi Adeyemi’s Children of Blood and Bone right now and can’t wait to crack it open cause ya girl is LATE to that party.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I am utterly confused that Harmony Holiday doesn’t have a Pulitzer and a MacArthur by now. Her work in and out of poetry dives deeply and sharply into the massive archive of Black American history and somehow emerges from all that familiar, lived history with something that feels completely new, completely original.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

My own ways and doubts. America. The rent. Being a Leo. Time. Depression. Long naps.

7. What trait do you most value in your editor (or agent)?

Jeff Shotts is like a good doula. He provides all the advice and encouragement and can be a brilliant guide, but he knows to leave the pushing and the decisions to you. His editing style makes me feel not like my work is being “edited,” but investigated, interrogated, and uplifted.

8. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

You know what would be a brilliant and vital fellowship? The “Pay My Insurance Premium” fellowship. I think money is great, but if there were structures around supporting the life and health of writers, I would weep for us, for the good done to the world of words. Some places have institutions focused on this work. In Minnesota, places like Springboard for the Arts are doing amazing work, but I would love if there were more large programs taking up the challenge of assisting folks make a life with room to write.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

My poet friends. The lot of them. Folks in the Dark Noise Collective and folks like Sam Sax and Hieu Minh Nguyen. They know when to praise and when to call me on my BS in perfect measure. At this point, I feel like I write with them over my shoulder. I trust my own eye more because I have spent so much time seeing myself through their keen lenses.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

“Stop writing what you know you already know in the ways you know you can write. Write towards what you want to know in ways you’re not sure you can.”