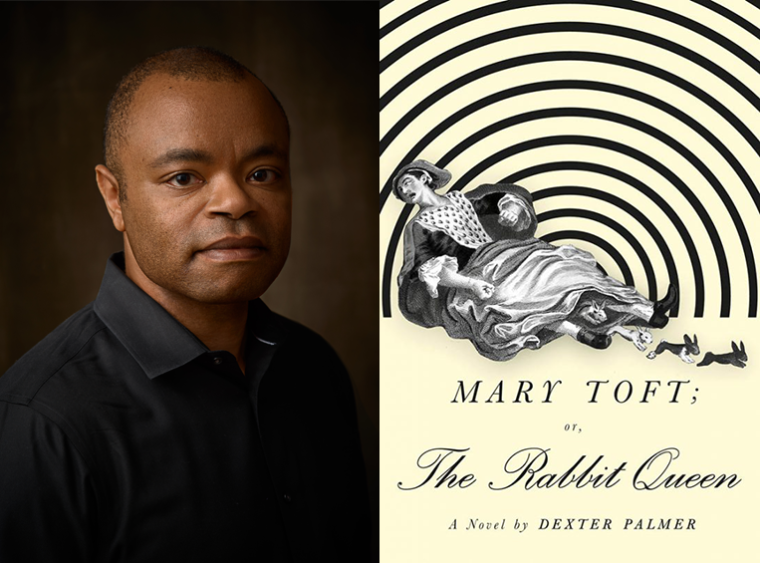

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Dexter Palmer, whose third novel, Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen, is out today from Pantheon. A work of historical fiction, Mary Toft reimagines the story of a woman from the English countryside who, in 1726, shocked the nation’s best doctors by giving birth to dead rabbits. In Palmer’s telling, the local surgeon John Howard and his assistant Zachary Walsh run from the room retching after witnessing the first delivery. A man who prizes his rationality, John is disturbed less by the matted fur and blood than by how such a miraculous birth might disrupt his entire belief system. As news of Mary’s case spreads, she and her growing company of doctors are summoned to London by King George, where onlookers crowd outside her window anticipating another birth. Tested in new environments and circumstances, the characters’ hearts are ever-changing; illusions are both lost and acquired. “It is vividly composed and audaciously imagined,” writes Kevin Brockmeier of Mary Toft. “Filled with characters who do battle against a world that perceives them as strange—or who, conversely, assume strangeness as a mask in order to induce the world to see them at all.” Dexter Palmer is the author of two previous novels, Version Control (Pantheon, 2016) and The Dream of Perpetual Motion (St. Martin’s, 2010). He lives in Princeton, New Jersey.

Dexter Palmer, author of Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen.

1. How long did it take you to write Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen?

Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen took me about three years to write, which is fast for me—my previous novel took about seven, and the one before that took fourteen. Part of the increased speed is perhaps because I have a better idea of what I’m doing now as a writer; part of that is because it’s my shortest novel at just over 100,000 words.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The most challenging thing about the novel was writing the first fifty or so pages, when I first realized just how much I needed to know about my chosen setting—England in the year 1726. Most of that first year of composition was taken up with teaching myself how to do the necessary research. I spent a lot of time in libraries trying to figure out what a house would look like, or what people would eat and how they’d cook it, or how surgeries were performed. Sometimes at the end of an eight-hour day I’d have a single paragraph to show for it.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

For this particular book I wrote whenever I had the time. There wasn’t much of a fixed pattern. Sometimes I’d knock out a few pages of dialogue in a single day; sometimes most of the work happened in my head rather than on the page. Usually, a day in which I get down 500 words that I don’t want to throw away is a successful one for me.

4. What are you reading right now?

Right now I’m reading Edoardo Albinati’s The Catholic School, which I’ve been working away at for the past couple of months—I’m on page 1,148 of 1,268. It’s interesting, even if the book jacket’s description of it as a “true-crime story” is possibly the most inaccurate claim I’ve ever seen in jacket copy. Sometimes Albinati’s thinking in it is original and surprising; sometimes he expresses familiar ideas in novel ways; sometimes I find myself persevering through the book only to bear witness to the heroic effort of the translation.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Molly Patterson’s novel, Rebellion, is probably the best debut novel I’ve read in the past five years or more. It’s so accomplished at a sentence-by-sentence level, and so elegantly structured, that it doesn’t even feel like a first novel most of the time. But it also has what I think of as good “first-novel energy”: It’s stuffed almost to bursting, as if the writer wasn’t quite sure she was going to get a crack at a second novel, so everything was going to have to go into this one. I wish that book had gotten more attention.

6. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I’d teleport one major New York City publishing house, buildings, personnel and their families, equipment and all, to a city in a Southern state, and another to somewhere in the southwestern United States, outside California. Say, Atlanta or Albuquerque. That’d do.

7. What trait do you most value in your editor or agent?

This is the second book for which Edward Kastenmeier was my editor, and I appreciate his holistic view of the work—my books have tended toward somewhat complicated structures, and he has a great eye for whether all the moving parts are meshing together correctly. Susan Golomb has been my agent for something like eleven years now, and she’s been tenacious no matter how odd the projects I’ve brought to her—she’s never asked me to dilute the content of a proposal to make it more accessible, and her eye when reading a manuscript is as good as any editor’s.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen, what would you say?

“As was the case with your other two books, when you reach the halfway point of the composition process you’ll wonder if this is working at all or whether you’ve wasted a lot of time. It’ll be fine.”

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I pick early readers for each book depending on the demands of the project, and I prefer to show works-in-progress to as few people as possible other than my editor and agent. For this one I went to a couple of old friends from England, Maria and Drew Purves, who I asked to make sure that I wasn’t introducing any inadvertent Americanisms and that I generally appeared to know what I was talking about; and to Brett Douville, a video game developer who was familiar with my earlier novels and who had some thoughtful observations.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

This is going to sound more nakedly capitalist than it is, but one of the things my editor said that helped with the writing of both my previous novel and this one was: “We want to be able to sell this book ten years from now.” Which is another way of saying that books that are rooted in the present moment can fade out of sight if they aren’t also able to speak to future readers. Some very good novels are ephemeral by design, meant by their authors to burn bright and quickly, but for the effort it takes me to write one, I prefer them to last longer.