This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Heather Lanier, whose debut poetry collection is out today from Monkfish Book Publishing. These contemplative lyrics interrogate the meaning of faith, attempting to square traditional Christian doctrine with the complex realities of contemporary life. At heart a quest for spiritual enlightenment, the collection blends reflection with wry humor and irony to unpack the contradictions of religious dogma and the speaker’s conflicted feelings. “Mary, did they wag their fingers no / at unpasteurized milk? Did you have to count / your protein for too little and your tuna / for too much, fretting mercury might metalize / the haloed brain of the divine?” the pregnant speaker wonders in “The Messiah Could Have Gotten Listeria.” Motherhood is a major theme of the book, which tracks the transformation of the female body and mind during gestation, childbirth, and the subsequent years of attempting to balance family, work, friendship, and life’s daily difficulties and rites of passage. Kirkus praises Psalms of Unknowing, calling it “a powerful poetic reckoning with motherhood and religion.” Heather Lanier’s essays and poems have appeared in the Atlantic, Salon, Time, and elsewhere. The author of the memoir Raising a Rare Girl (Penguin Press, July 2020), she is an assistant professor of creative writing at Rowan University in New Jersey.

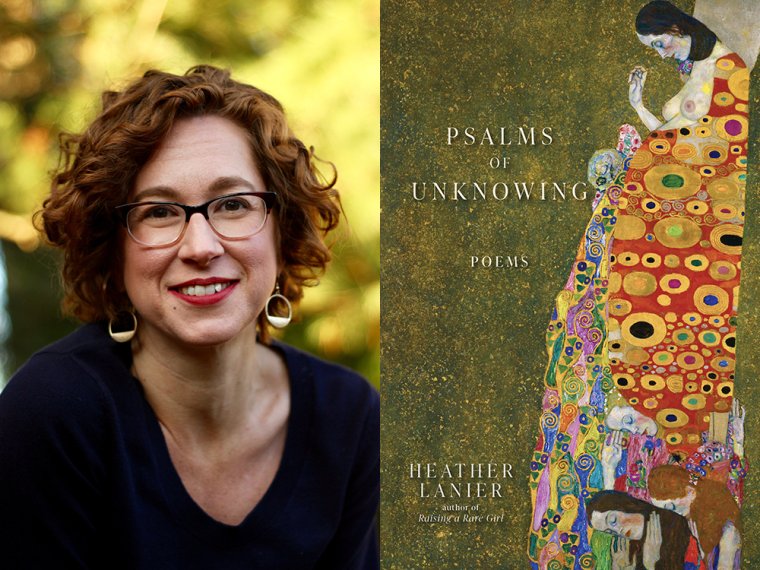

Heather Lanier, author of Psalms of Uknowing. (Credit: Justin Lanier)

1. How long did it take you to write Psalms of Unknowing?

In some ways, forever. I wrote the oldest poem in the book eighteen years ago. But most of the poems were written in the last decade, maybe even the last five years. (Meanwhile, I was also writing nonfiction.) I spent about a year thinking about how the poems would become a book.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Putting it all together. I had almost two decades’ worth of poetry. I’ve assembled chapbooks before, and the chapbook length holds a single theme well. But full-length books often need multiple thematic strands interwoven. You want a book of poetry to create surprise, but not discord. You want variation without jarring interruption. And you want a conversation. It’s tricky. I tried a lot of different groupings of poems. But once I found a central throughline, feminist spiritual seeking, everything fell into place. All the other themes—pregnancy, grief, motherhood, political rage, religious questioning, etcetera—were filtered through that lens.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

It depends on the season. I shift my goals based on what’s possible. My ideal is to write five days a week, two hours a day, in the morning after my husband and I get the kids to school. That’s possible during certain periods of the semester, and not at all during the summer. When the semester gets super busy, I aim to just open a Word document (or the writing app Scrivener) every weekday and sit with it for at least thirty minutes. The summer is chaos. I have to get creative. Regardless of the season, I almost always write at home—at my desk, on a couch, or at the dining table.

4. What are you reading right now?

A friend recommended Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength by Roy F. Baumeister and Denis O’Hare, so I’m reading that. Fascinating stuff. (I wrote a little bit about it here.) I just finished my friend James Crews’s lovely book, Kindness Will Save the World: Stories of Compassion and Connection, and on deck I’ve got Camille T. Dungy’s Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden and Carolyn Hays’s Letter to My Transgender Daughter: A Girlhood.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I mentioned that I used feminist spiritual seeking as a throughline. So the opening poem, “Pumping Milk,” sets that up, with the figure of a half-naked woman getting ready to pump milk at the office and asking questions about what it means to be human. After that the book is arranged in four sections. I didn’t want any of the sections to feel too monolithic (as in, And now the Pregnancy Poems!). Each section contains at least two threads that are a bit contradictory so that the contrasting notes speak to each other to create a third thing. For instance, the first section focuses on pregnancy and grief. By pairing poems about carrying life with poems about losing it, the first section creates a larger conversation about the risks we take in living and loving. Each of the book’s sections is subtitled with a feminist renaming of the parts of the Holy Trinity in the Christian prayer: “In the Name of the Mother...”, “And the Child...”, “And the Holy Unknowing...”, and “Amen.” So the entire book is structured around a (probably heretical) prayer that nudges female and nonbinary language into Christian tradition.

6. How did you arrive at the title Psalms of Unknowing for this collection?

The phrase “psalms of unknowing” appears in a poem called “Free Bible in Your Own Language.” I had been walking on a university mall when I spotted a booth with that phrase on a sign. And I was feeling snarky and amused by it. Like many people, I’ve felt plenty alienated by the language of the Bible, so I started riffing on what kind of language “my Bible” would contain. Curse words, 1980s pop music, and, ultimately, an ease with unknowing. That phrase, “psalms of unknowing,” pushes back against fundamentalism and makes space for a spirituality that emerges from doubt, uncertainty, and openness.

The title also echoes a book called The Cloud of Unknowing, an anonymously written text that is foundational to the contemplative Christian movement, which emphasizes receptivity to the divine. While my book is filled with lots of things—rage and silliness and sorrow—it’s guided by the spiritual practice of receptivity.

7. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I would! Especially if you want concentrated time to study your craft. But I’m not a fan of going into debt for one. I encourage people to aim for fully funded programs, or low-residency programs where you can keep your job. I had an amazing time at Ohio State University writing for three years, teaching college students, and living on my $1,200-a-month stipend. But that was when you could rent an apartment in Columbus, Ohio, for $400 a month. (Also, my apartment had raccoons in the pantry—so, you know, tradeoffs.) With the expensive housing market, I know it’s harder to avoid loans for living expenses. But universities should be supporting their grad students with tuition waivers and fair stipends.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Psalms of Unknowing, what would you say?

I’d say, “Just keep going.” I guess what I mean by that is: Just keep listening to the work, one poem at a time. I’d also say, “Don’t fear motherhood. It will be the best thing for your writing.”

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I took a class on how to assemble a poetry collection, with Nancy Reddy at Blue Stoop. My graduate degree did a great job of helping me write individual poems, but we didn’t spend much time in courses learning how to shape a collection. I needed help. Nancy was great.

I also had to deconstruct my fundamentalist upbringing, spend a decade rejecting Christianity, relearn it through a Buddhist lens, and spend another decade practicing contemplative meditation. And there was that whole getting-pregnant-with-two-children-and-giving-birth-to-them thing. But more specifically, I spent a week at a monastery on a silent retreat, meditating with a group of people. That’s where the final poems in the book come from.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Isak Dinison’s quote—as passed down by my mentor, Lee Martin—the last word of which I technically misremembered. Here is my version: “Write a little every day, without hope or fear.”