This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kaitlyn Greenidge, whose second novel, Libertie, is out today from Algonquin Books. A sweeping historical novel, Libertie begins in the Reconstruction era in Brooklyn, New York. The eponymous protagonist is eleven years old, and in the opening scene she watches her mother, a local doctor, revive a man who has just been smuggled north to escape slavery. If at first Libertie is fascinated by her mother’s work, she increasingly chafes against the expectation that she, too, will become a doctor. Greenidge maps Libertie’s life as it unfolds, from New York to Ohio to Haiti, and her pursuit of a life in music. Through Libertie’s eyes, Greenidge records the subtle and overt violence of racism, colorism, and misogyny, while meditating on what freedom might look like. “This is one of the most thoughtful and amazingly beautiful books I’ve read all year,” writes Jacqueline Woodson. “Kaitlyn Greenidge is a master storyteller.” Kaitlyn Greenidge is the author of a previous novel, We Love You, Charlie Freeman, which was a finalist for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize. She is a contributing writer for the New York Times, and her work has also appeared in Vogue, Glamour, and the Wall Street Journal, among other publications. The recipient of fellowships from the Whiting Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, she lives in Brooklyn, New York.

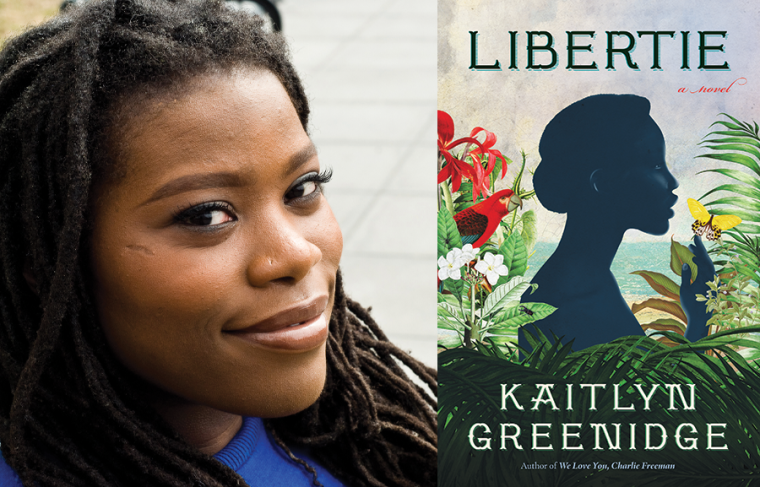

Kaitlyn Greenidge, author of Libertie. (Credit: Syreeta McFadden)

1. How long did it take you to write Libertie?

It took about three years in total. I came up with the idea for the book in the spring of 2016. I spent about a year just thinking about how it might work, reading and researching pretty slowly. I was overwhelmed with the technical challenge of setting part of the work in Haiti, a country I did not yet know well; in Kreyol, a language I did not speak; and during the 1870s, a time period in Haiti that is hard to find much information about in English. We have a lot of English books about the Haitian revolution at the start of the nineteenth century and U.S. intervention in Haiti in the twentieth century, but the time period I was looking at seemed more difficult to find. Luckily, I started e-mailing academics and writers and poets during that year and I found my way.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Probably figuring out how all the different elements would work cohesively. I knew what I wanted in the book, but convincing the reader that those things were in there for a reason was the challenge.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I don’t follow a set schedule. I write and rewrite constantly in my head, often e-mailing myself lines or images or ideas. In 2018 I was very lucky to receive a fellowship at the Radcliffe Institute, which meant for the first time in a very long time I could write fiction every day. That was great—I came to my office by about 10 AM, wrote till about 2 PM, and then did nonfiction work in the afternoons. But then I got pregnant and had to rethink my fellowship time, so that schedule only lasted for about four months.

4. What are you reading right now?

Sarah Schulman’s Let the Record Show, which is an absolute game changer. Both in revealing more information about the history of ACT UP and in demonstrating how to use oral histories and write about social movements and organizing. I love it a lot. I just finished Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters, which is just so satisfying and perfect. So many times in the last few years I’ve been told a novel is the novel of millennials, and I’ve been like, “Which millennials are you talking about? Not anyone I know.” Detransition, Baby feels like the last decade of my life. It’s so familiar.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Simone Schwarz-Bart. The Bridge of Beyond is, on the sentence level, an absolute masterpiece of a novel. I don’t know how she did it. I read it twice while writing Libertie.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Time. There’s never enough of it.

7. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

It’s a highly personal decision. It all depends on the program you get into and whether the particular mix of instructors and students fits your particular needs at a particular point in your artistic life. I don’t think it’s helpful to be prescriptive about it.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Libertie, what would you say?

Keep going and do the hard stuff first.

9. What, if anything, will you miss most about working on the book?

The research and the characters. I loved them all and I also loved figuring out how to fit all these weird, wonderful pieces of history into the book.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

There’s no perfect writing advice. It all depends on your particular artistic moment. But if you are in this for the long haul, it’s valuable to know that all you understand about yourself as an artist—your working habits, your interests, your needs—will shift as you grow and life changes. It’s helpful to expect that and roll with it rather than mourn a past perfect writing life or long for a future one that is never coming.