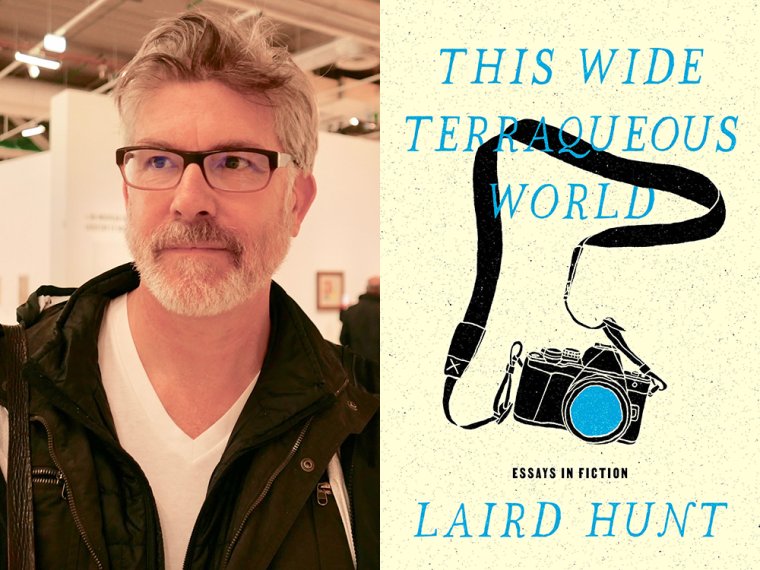

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Laird Hunt, whose essay collection, This Wide Terraqueous World: Essays in Fiction, is out today from Coffee House Press. Part autobiography, part meditation on the writing life, the novelist’s debut nonfiction collection takes readers along on a lifetime of travel, from an early childhood in Singapore, to a young adulthood working for the United Nations, to more recent adventures with his wife and daughter in North Africa, Europe, and stateside. Literature accompanies Hunt wherever he roams, as a literal volume carried with him or as a lens through with he views the scene: Jane Bowles in Palermo, Virginia Woolf in London, Jorge Luis Borges in Marrakech, and everywhere his own writing. One of the pleasures of the book is its window into the life of a contemporary literary family: Hunt is married to the poet Eleni Sikelianos, presumably the “Eleni” who appears throughout the collection. Readers witness the couple and their daughter, Eva, attend readings, visit museums, or savor life closer to home. A notes section at the back of the book offers photographs to accompany the essays. Kirkus calls This Wide Terraqueous World “a slim, elegant attempt to describe the curious alchemy of fiction writing,” praising Hunt’s “poetic sensibility.” Laird Hunt is the author of eight novels, including the 2021 National Book Award finalist Zorrie. He is the winner of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for Fiction, the Grand Prix de Littérature Américaine, and the Bridge Prize.

Laird Hunt, author of This Wide Terraqueous World. (Credit: Eva Sikelianos Hunt)

1. How long did it take you to write This Wide Terraqueous World?

The pieces in the book were written over a period of twenty years, with the most recent one completed a couple of years ago.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

This is my first-ever collection of essays, so it’s uncharted territory for me—novels being where I’ve spent the majority of my writing time—and just about everything was challenging. I gave myself the added hurdle of deliberately allowing fiction into the mix, so getting the balance between fiction and nonfiction was very important and not so easy.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

My green desk is on the second floor of our house and looks out onto a Callery pear tree and a sugar maple. I’m often to be found up there in the morning. No set schedule: just a tendency in recent years to be matinal.

4. What are you reading right now?

Antony Beevor’s Crete 1941: The Battle and the Resistance and Andrei Tarkovsky’s Sculpting in Time: The Great Russian Filmmaker Discusses His Art.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Michel de Montaigne’s genre-opening essays were one of my first great literary loves and are never too far from me. Clarice Lispector’s crônicas—recently available in their entirety in Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson’s translation from New Directions in Too Much of Life: The Complete Crônicas—have been hugely important. And more recently Selah Saterstrom’s marvelous Ideal Suggestions: Essays in Divinatory Poetics has been a touchstone.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of This Wide Terraqueous World?

I have been very surprised to discover that the project of writing these essays in fiction would continue to feel fresh even as quite a few years went by. The present selection represents a little under half the pieces in this vein that I’ve written and, curiously, I plan to write more.

7. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

Many years ago in Holland, I went out on a snowy evening with a small, green-handled hammer, which a neighbor boy and I took to flinging back and forth at each other. Not so much a game of catch as a game of dodge the hard flying object. It was dumb (because dangerous) and entrancing (because dangerous and outrageous) and has seemed, at different times, to serve as an apt metaphor for events in the world and in my life.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started This Wide Terraqueous World, what would you say?

Read more! Listen more! See more! Feel more! Take better notes!

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Two things. 1. Much of the observing and thinking that went into the book was done while I walked, for hours and hours at a time, in both urban and nonurban locales. 2. The majority of the pieces in the book were inspired by my long-term, though still totally amateur, practice of taking snapshots with an Olympus PEN micro-four-thirds camera, which I have deployed locally, around town, and wherever I have had the good fortune to travel.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

The late poet Robert Creeley once turned to me—in light of some self-deprecating remark I had made about my most recent book and projects—and told me, “Be serious!” In a world that seems to care very little about what writers get up to, I have done my best to take that to heart.