Among the many new books published each season is a shelf full of notable anthologies, each one showcasing the work of writers united by genre, form, or theme. The Anthologist highlights a few recently released or forthcoming collections, including When the Smoke Cleared: Attica Prison Poems and Journals (Duke University Press, November 2022).

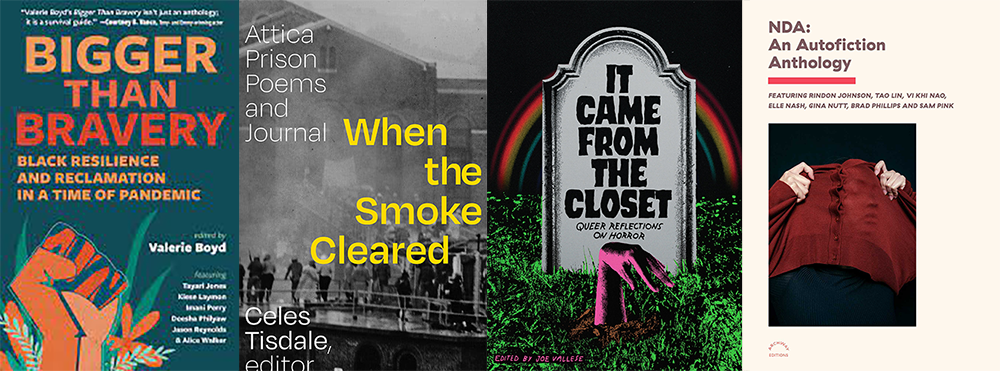

Before she died in February, writer and academic Valerie Boyd edited Bigger Than Bravery: Black Resilience and Reclamation in a Time of Pandemic (Lookout Books, November 2022). Crafted as an act of resistance to despair during the COVID-19 pandemic—which has disproportionately affected African Americans—Bigger Than Bravery gathers poetry and prose from thirty-one Black writers whose words offer “comfort as we reach toward the promise of brighter days ahead,” Boyd writes in her introduction. In “The Quarantine Album: Liner Notes,” Deesha Philyaw offers a playlist of sorts, tracing her movement through the pandemic according to “tracks” with names that have become all too familiar: “Who’s Zoomin’ Who” and “Computer Love,” which explore the ups and downs of digital relationships, and “All the Single Ladies,” which considers the pain of lockdown for the “touch-starved and weary.” In “False Dawn: A Zuihitsu,” poet Khadijah Queen charts the rising number of deaths across the globe: “Count every one. Keep counting,” she writes in one section, while enumerating brighter details in another: “Artichokes, asparagus, aspens, autumn. I list what I appreciate.” The life-giving force of food also permeates Destiny O. Birdsong’s “Build Back a Body,” in which she finds a new appreciation for meal preparation: “I’ve never been loved through the sharing of cooking in a way that empowers me to make food on my own until now, when it has become one of the many iterations of my relationship with Josh and Claire during shutdown,” she writes. In “Memorial Day 2021,” Opal Moore mourns the loss of George Floyd while exalting his life: “Dear invisible man / you are not buried / at Arlington though // some would call you war hero,” she writes. Taking its title from a phrase in Jericho Brown’s poem “Crossing,” Bigger Than Bravery is a last gift from Boyd to the reader: “a glimpse into your own bravery, your own greatness, your own transcendent freedom,” she writes.

In September 1971, people imprisoned at Attica Correctional Facility in Western New York State rebelled against inhumane living conditions in what would become the deadliest prison uprising in U.S. history. A year later, Celes Tisdale began a weekly poetry workshop for those incarcerated at Attica, which he led until 1975. When the Smoke Cleared: Attica Prison Poems and Journals (Duke University Press, November 2022) documents those workshops. The volume includes the entirety of Betcha Ain’t: Poems From Attica, edited by Tisdale and published in 1974 by Broadside Press, along with previously unpublished poems by the Attica poets, poetry by Tisdale himself, Tisdale’s journals, and a critical introduction by poet and activist Mark Nowak. When the Smoke Cleared offers a moving window into life inside the U.S. carceral state during the twentieth century, humanizing men whose incarceration in Attica led many to dismiss them as one-dimensional criminals. In “Attica Reflections,” Hersey Boyer captures the lachrymal sounds inside the prison after dark: “It isn’t strange to awake in the silence / Of midnights, // To hear MEN weeping, in harsh and gravelly voices / That turn away your lies.” In “Buffalo,” Jamail (Robert Sims) recalls Allen Ginsberg’s Howl in a depiction of a “drag town” gone mad: “I ran through it screaming. / I saw drugged drags nodding / into oblivion,—dying as painlessly as vile odors.” Other poems evince hopefulness, as in Theodore McCain Jr.’s ode to singer Mahalia Jackson: “Remember Mahalia. / Her voice echoed around the world, / Singing songs of days of triumph.” In his journals, Tisdale records workshop activities, often praising students’ progress: “The men have become quite sophisticated in their poetic tastes and versatility,” he writes in an entry from December 20, 1972. In his introduction Tisdale recalls how he “encouraged the men to know their worth and take pride in their work,” describing his motivation for editing the new anthology: “I wanted the world to know them as poets of pride and confidence in this offering.”

Popular horror cinema is often overlooked by those for whom the kitschy, campy, and titillating tropes of the genre register as signs of schlock. Yet by tapping into a culture’s collective fears and taboos, horror can prove as revelatory as any supposedly “high” art form. For LGBTQ people, horror offers a poignant lens through which to “consider and reflect upon queer identity,” writes Joe Vallese, editor of It Came From the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror (Feminist Press, October 2022). In this wide-ranging collection, more than two dozen writers offer personal takes on horror and its intersection with not only queerness but also race, religion, disability, and other identity markers. Each essay interrogates a particular movie, mining it for insights into the writer’s lived experience and the larger sociopolitical sphere. In “A Demon-Girl’s Guide to Life,” for example, S. Trimble considers their evolving understanding of The Exorcist. Labeled “Manwoman” by their seventh-grade classmates in the 1990s, Trimble first identified with the film’s adolescent protagonist Regan, whose demonic possession may be interpreted as nonnormative gender expression as seen through cisgender, heteronormative eyes: “girlhood gone awry,” as Trimble puts it. Later Trimble comes to see The Exorcist as a mirror for rightwing Christian panic about the breakdown of the white nuclear family and, later still, as a commentary on closeted suffering through the character Father Karras. Carmen Maria Machado offers an ode to Jennifer’s Body, arguing that it deserves more credit for its complex depiction of bisexuality than the widely panned 2009 film has been given, even among queer viewers. Other contributors include Jen Corrigan on Jaws, Viet Dinh on Sleepaway Camp, Zefyr Lisowski on The Ring and Pet Sematary, and Prince Shakur on Good Manners, or As Boas Maneiras, a Brazilian werewolf flick. “Like the best horror films, these essays will both satisfy and subvert expectations,” Vallese writes. “Consider yourself warned.”

Narratives that collapse the distance between writer and protagonist have become a hallmark of twenty-first century fiction. This nebulous boundary troubles some readers, prompting “moral, academic, and critical scrutiny,” writes editor Caitlin Forst in a concise note at the start of NDA: An Autofiction Anthology (Archway Editions, November 2022). Tongue planted firmly in cheek, Forst assures the reader that the volume in hand reflects no such scrutiny: “I am not moral, academic, or a critic.” Forst’s ironic tone characterizes much of the work in NDA. Take Vi Khi Nao’s “Field Notes on Suicide or the Inability to Commit Suicide or It’s Hard to Follow a Pomeranian Around,” in which the depressed narrator gets kicked out of Starbucks in Las Vegas and wonders bemusedly about various ways to die: “Is it sinful to be trampled by a mini-van, by two adults on their way to the Bellagio to see the fountain dance the night away?” Later the United States’ post-9/11 wars in the Middle East are summarized in a surreal non sequitur: “And then in 2001, the US got involved in a very romantic relationship with a fake nuclear psychoanalyst called Afghanistan.” The banality of violence is a running theme throughout the collection, as in Sam Pink’s “3:40 PM,” which opens in medias res at a nameless bar: “And then, like it always does, the conversation turns to horrific injury and tragedy.” Patrons discuss being impaled while on television “a man catches a football in spectacular fashion.” In Tao Lin’s “Canadian Gay Porn Site,” the novelist narrator considers working as a pornographic actor as part of his ongoing project to simultaneously court and avoid mainstream success: “I...wish, even, to make myself even more ‘unavailable’ to larger publishers,” he writes. Wry, deadpan, and laced with cynicism, the selections in NDA offer a crash course—by turns maddening and delightful—in a literary milieu for which the word milieu would only provoke eye rolls among its denizens.