It is raining in Palo Alto, California. A shift in the Gulf Stream has pulled a cold front down from the Pacific Northwest. Students and teachers on the campus of Stanford University, where Tobias Wolff has taught creative writing since 1997, are decked out in crimson school sweatshirts and brightly colored rain slickers. Leaves tumble across the wet sidewalk behind Margaret Jacks Hall as I enter the building on my way to Wolff’s book-lined, paper-piled office.

Given the psychological terror of his best work—stories like “Hunters in the Snow” and “Bullet in the Brain,” for example, both of which are included in his new book, Our Story Begins: New and Selected Stories, published this month by Knopf—I half expect to meet a brooding, troubled man; a match for the dark imagination on display in much of his work.

I do not.

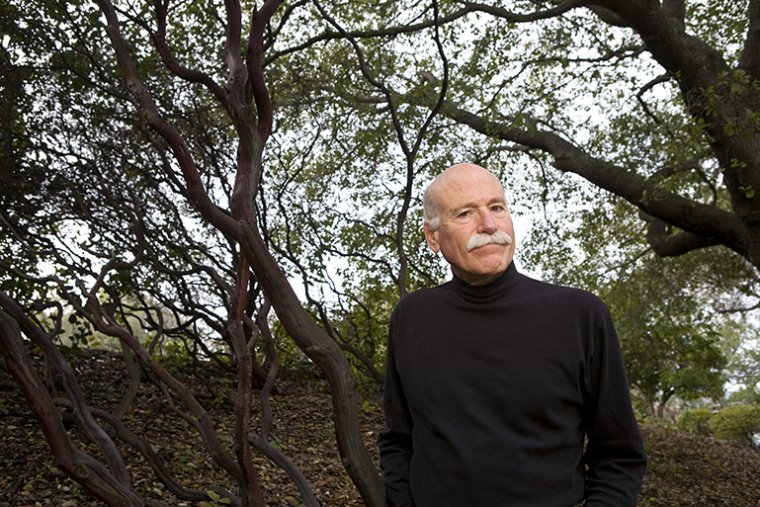

The sixty-two-year-old author is aging gently. His hair is clipped close to the head, his mustache thick and bushy. Today he’s dressed in a tenured professor’s standard-issue uniform—thin, wire-framed glasses, blue jeans, and a soft, open-necked polo shirt. It’s exactly how he appears in nearly every photo of him I’ve been able to uncover.

His office looks like a true writer’s den, an orchard of piles: Books and papers and manuscripts stretch toward the ceiling. An overstuffed bookshelf runs the length of an entire wall. Against another wall is Wolff’s desk. Sitting there he faces a bulletin board of family photos, and at the farthest end of the office, next to the door, is what he describes as his “little shrine,” dedicated to his friendships with Raymond Carver and Richard Ford. The triptych leads off with a single 8 x 10 black-and-white photo of “Ray”; below it are similarly sized black and whites of Carver, Wolff, and Ford together in what he says is England, 1985. He smiles broadly as he points them out to me.

“He was a dear friend of mine,” he says, referring to Carver, and like any fan of the late minimalist writer—the poet of American suburban despair, he’s been called—Wolff holds strong opinions about the quest by his widow, Tess Gallagher, to publish the unedited manuscript of his groundbreaking 1981 collection What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, which was edited heavily by Gordon Lish, Carver’s editor at Knopf. Lish cut the stories almost by half, and rewrote the majority of their endings. Gallagher’s plan is to publish the original versions of the stories under a title Carver initially gave to one of the stories: “Beginners.”

Wolff is plainspoken about the topic. “Ray had a chance in Where I’m Calling From to use whatever version of his stories he preferred,” he says, referring to Carver’s volume of selected stories, which was published in 1988, the same year he married Gallagher, a few months before he died of lung cancer. “These were, to him, the final versions of his stories. He was no longer under the hand of Lish; he was in fact working with Gary Fisketjon at the time. He had the chance to present the final version of each story, and he did. Some of those stories had greatly changed under Lish’s editing and in some cases he preserved Lish’s edits because he decided that those edits strengthened the work. Ray made these decisions freely, without pressure from anyone. Lish had effected radical changes in tone and voice in many of the stories in What We Talk About When We Talk About Love, and in certain instances—‘A Small, Good Thing,’ for example—Ray chose to return to something closer to his original version, but in others he favored the later form. He had his chance to go back to the originals and he didn’t do it.”

To Wolff, Carver was not just a personal friend, though he was certainly that. His connection to the author stretches back more than thirty years. Both received Wallace E. Stegner Fellowships at Stanford University—Carver in 1972, Wolff in 1975. In 1980, they both joined the faculty of the creative writing program at Syracuse University (where Wolff went on to nurture the talents of such writers as Jay McInerney, George Saunders, and Alice Sebold). But perhaps the strongest link between Wolff and Carver was forged in the summer of 1983, when the British literary magazine Granta labeled their work—along with that of Ford, Jayne Anne Phillips, Frederick Barthelme, Bobbie Ann Mason, and others—“dirty realism.” The designation stuck. Dirty realism as a style was revisited by the magazine three years later with the release of Granta 19: More Dirt, which featured, among others, Joy Williams, Richard Russo, Ellen Gilchrist, and Louise Erdrich—even John Updike made the cut.

While diverse in both style and choice of content, these writers share a devotion to clarity, brevity, and finding heroic stories (and antiheroes) in the lives of the “average” or “below average” American—less educated, sometimes poor, nearly always desperate. Certainly Wolff’s work is exemplary. He writes with the exacting precision of a bombmaker. With steady hands and sinister ambitions, he crafts his best fictions in miniature, detonating his characters’ lives in the time it takes to read a paragraph, crafting tales that turn on a single diabolical sentence. Wolff is widely acknowledged as a master of the short story, more specifically of the short short story form, but he has also written novels and memoirs in a signature style that explodes from the page, brilliantly illuminating the submerged and the sequestered, the things ordinary men and women try to hide from the world.

While he is not extraordinarily prolific, the consistency of Wolff’s output over the past thirty years is difficult to match. He has published four celebrated collections of short stories; the novella The Barracks Thief (Ecco, 1984), which won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction in 1985; the memoirs In Pharoah’s Army: Memories of the Lost War (Knopf, 1994) and This Boy’s Life (Grove, 1989); and the novels Ugly Rumours (Allen and Unwin, 1975) and Old School (Knopf, 2003), which was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, PEN/Faulkner Award, and National Book Critics Circle Award. Among his other honors are the PEN/Malamud Award and the Rea Award, both given for a body of work that has demonstrated excellence in the short story form.

The publication of Our Story Begins will likely further cement his stature as an American master of the story, as well as introduce him to a new, younger readership. The book gathers the best from his three earlier collections: In the Garden of the North American Martyrs (Ecco, 1981), Back in the World (Houghton Mifflin, 1985), and The Night in Question (Random House, 1996). A number of these stories, including “In the Garden of the North American Martyrs” (1981), “Next Door” (1982), and “Sister” (1985), were bestowed the genre’s highest honor, the O. Henry Award.

Stylistically, only Carver and perhaps Joy Williams write sparer prose, and only Carver has as many classic short short stories still read today—one of the reasons Wolff disagrees with the idea of revising history and publishing “original” versions of Carver’s work. “I would not consider it an act of friendship if this were to happen to me. I have stacks of drafts over there on the floor,” Wolff says, pointing, “or drafts I have submitted to magazines and later revised for my books, and then again for later editions. I would not consider it a favor if someone were to publish those first drafts. I would not. This is being touted as a restoration and it’s putting transitional work in competition with his own vision of what is best in his fiction. I don’t like it. I think it seriously muddies the water.”

In a preface to Our Story Begins, Wolff considers the question of whether to present his own earlier stories in their original form or to revise them. “There appears to be a good argument for the first approach,” he writes. “It could be said that I am no longer the man who wrote a story published twenty-five, or ten, or even two years ago, and that I should be a respectful executor and do the actual, now-vanished writer the honor of keeping my mitts off his work.”

Although Wolff says he didn’t substantially rewrite any of the stories in the new collection, he did find a few words, a few sentences, that just didn’t need to be there. “Those little housekeeping things,” he calls them. “I certainly notice them when I’m reading other people’s work, and I didn’t want to put anything out myself that I would wince at in another’s story.”

When rewriting new work, on the other hand, Wolff regularly changes endings or characters, names or histories. Indeed, Wolff calls rewriting his favorite activity as a writer. “It is the one time you don’t have the anxiety of whether you’re going to be able to finish the damn story at all, which is always there to some extent. I love rewriting and I probably spend altogether too much time doing it.”

For the most part, however, this rewriting is done long before one of Wolff’s books lands in the hands of his editor at Knopf—one more thing Wolff and Carver have in common. Fisketjon, who helped the late author make selections for Where I’m Calling From, is Wolff’s longtime editor, and it’s clear they have a professional relationship based on respect. “The editors that I’ve worked with always felt free to make suggestions,” he says. “But I’ve never had an editor tell me I must do something. Gary put it very beautifully to me once; he said, ‘I propose, you dispose.’”

Wolff says he weighs all of Fisketjon’s suggestions carefully, but in the end—whether he finally agrees with them or not—his editor never revisits those marks again. “I dread it, the editing,” says Wolff, “but I’m always glad when it’s done. To see your own work through someone else’s eyes for a moment is helpful. Some writers are very jealous of their writer’s prerogative—this sense of the solitary genius cranking out work too sacred for a second thought, I don’t know. My own experience is you can learn something from others. I certainly have.”