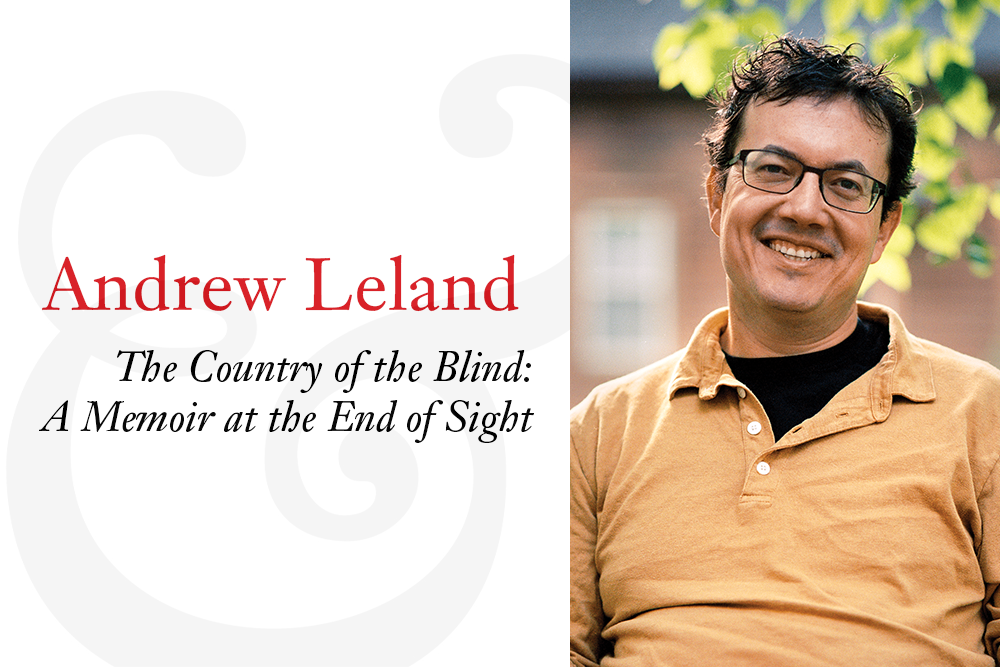

The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight (Penguin Press, July), a debut book of nonfiction that combines personal narrative and historical and cultural investigation to explore the experience of the gradual transition from full vision to blindness in a moving portrait of not only the physical experience of blindness, but also its language, politics, and customs. Agent: Claudia Ballard of William Morris Endeavor. Editor: Emily Cunningham. First Lines: “I’m going blind as I write this. It feels less dramatic than it sounds. The words aren’t disappearing as I type. I’m sitting comfortably in the sunroom. The sun is rising like it’s supposed to. I can plainly see Lily sitting next to me, reading in her striped pajamas. The visible world is disappearing, but it’s not in a hurry. It feels at once catastrophic and commonplace—like reading an article about civilization’s imminent collapse from the climate crisis, then setting the article down and going for a pleasant bike ride through a mild spring morning.” (Credit: Gregory Halpern)

![]()

I have known I’ve been going blind for a long time. But for decades, blindness felt distant and abstract. The degenerative retinal disease I have, retinitis pigmentosa, causes one to lose vision gradually, from the outside in. It’s only in the past five years or so that blindness has become an immediate condition that touches the most intimate parts of my life. At the same moment that my need to learn blindness skills became more urgent, so did my desire to write about it. I knew I didn’t want the book to be pure memoir. There were a few reasons for this: There are already so many excellent blindness memoirs in the world, and I felt far from the place most of their authors begin from, having already gone blind and reflecting on the experience. I was—and am—still in the slow thick of it.

I also felt a strong urge to write about the world of blindness beyond my own experience. To my surprise, in addition to the traditional negative emotions—fear, grief, anger—vision loss generated a powerful and persistent curiosity about the world of blindness and disability. I wanted to understand how my experience diverged from—or was beginning to resemble—other blind people’s lives throughout history. I wanted to explore larger and increasingly existential questions I found myself obsessing over: how understanding the world through four senses changed one’s relationship with art and literature, images and information, strangers and intimates, political action, and one’s own identity. That was the book I hadn’t quite encountered before: one that used the experience of vision loss to get at material that strayed energetically from the memoiristic into journalistic, critical, and philosophical territories.

The biggest challenge in writing and revising the book was weaving together these two strands. My first draft suffered from what my editor, Emily Cunningham, described in her first memo to me as an imbalance between “personal narrative and what I’ll inelegantly call ‘everything else’—more detached reported material and history.” The text resembled a collage: long, personal, colorful scenes of emotional reckoning, slammed up against short Wikipedian historical narratives. How to integrate these two modes? In my second draft I swung too far in the other direction—Emily now informed me in her unfailingly polite but persistent way that large swaths of the new draft felt eye-glazingly dutiful and narrow. Which indeed they were—I was trying to satisfy her request for all that cultural and political history of blindness I’d promised in my book proposal. She disarmed me with a compliment: When you’re interested in a subject, she told me, you can make anything feel engaging. But if you’re not into it, it makes for tough reading.

This compliment was the soundtrack playing in the background of my last major revision: I cheerfully slashed all those dutiful passages of my warmed-over glosses on European Enlightenment philosophers’ speculations on blindness and instead wrote what felt urgent, fun, fascinating, relevant. Emily’s note also freed me to write cultural and political history that seemed connected to my personal narrative, since I was writing from my own experience, my own interest, rather than trying to cover the waterfront in the imaginary college-level disability-studies curriculum I thought I’d needed to follow. This third draft put the pieces in place, mostly, and left Emily and me to home in on the remaining, more isolated sections that had retained the stench of the dutiful, which felt at once terrifying and exhilarating to cut and rewrite up until the final deadline.