In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 147.

I want to talk about the quotidian and the code. These are what the novel is made of: the ephemera, the details, the everyday, and also the ancient narratives, the inherited structures, the myths.

The novel is made of days spent walking around the city of Dublin, and it is made of the voyage of Odysseus.

When the novel emphasizes the quotidian—when it’s steeped in the random details of daily life, when its myths are subordinated or occluded—it’s a realist narrative. When the novel emphasizes the code—when its details build purposefully toward the romance, the battle, the crime—it’s genre fiction.

The code is structure; the quotidian is fragment. The code is system; the quotidian is glitch. The code is theme; the quotidian is variation. The code is night, the dreamtime; the quotidian is day. The code is pattern; the quotidian is chaos. The code is tradition; the quotidian is modernity.

In his last lecture course, Roland Barthes explored the preparation of the novel. He wanted to know how one passes from what he called “Notation”—or “the Note”—to the novel itself. How does the writer get from the discontinuous to the flowing? He explained that the present is distinct from the topical: “The present is alive (I’m in the process of creating it myself) whereas the topical can only be a noise.”

Barthes’s notion of the topical resembles what he calls “studium” in his discussion of photography: the functional aspect of art, involving discipline, education, and the photographer’s intent. When he says present, he might be speaking of what he calls photography’s “punctum”: “the accident which pricks, bruises me.”

The quotidian pricks because it has no point. It’s beside the point. It might not be accidental, but it feels that way. It’s gratuitous, a surplus. In the realist novel, writes James Wood, “the margin of surplus itself feels like life, feels in some curious way like being alive.”

The novel is a narrative that is also made of this “margin of surplus,” or what Franco Moretti calls “fillers”: those everyday details that are “the opposite of narrative.” The novel consists of narrative and its opposite.

Narrative is told, passed on; its opposite is forgotten. The code is long-term memory. The quotidian is short-term memory. Short-term memory is ruptured and multiple. Long-term memory is continuous. It is family, society, civilization. Perhaps it is also planet.

Perhaps only the code has a memory long enough to approach the geologic, while the modern so-called realist novel, as Amitav Ghosh has argued, with its glut of quotidian detail, its obsession with the inner lives of its protagonists, amounts to “a concealment of the real.”

Ghosh is concerned that the modern novel cannot address climate change because it depends on probability. Developed in the era of statistics, under a regime of regular time, the realist novel banishes happenings considered unlikely, such as freak weather events, to the disdained genres of fantasy and science fiction. This suggests that the realist novel is not simply made of the quotidian and the code, but functions to separate those things: that this type of novel creates an opposite for narrative, an opposite that is privileged because it defines realism against older forms such as fairy tale and myth, as well as the contemporary rivals of genre fiction. So what Wood calls margin and Moretti calls filler, what’s described as peripheral and extraneous, is not merely characteristic of the realist novel; it constitutes its purpose.

This emphasis on the regular, ordinary, and everyday defines this quotidian literature not only against other forms of narrative, but also against life, which is stranger than fiction. This is why Ghosh, who experienced the first recorded tornado in Delhi, finds it impossible to describe the event in a novel.

“I buried my head in my arms and lay still,” he writes in a work of nonfiction. “Moments later,” he goes on, “the noise died down and was replaced by an eerie silence. When at last I climbed out of the balcony, I was confronted by a scene of devastation such as I had never before beheld.”

In a response to Ghosh, McKenzie Wark declares the obsolescence of the bourgeois novel in the Anthropocene. “Science fiction,” writes Wark, “is more, not less, ‘realist’ than literary fiction. It does not produce the fiction of a severed part of a world, as if the rest was predictable from the part. It produces a fiction of a whole different world as real.” But the problem Ghosh describes cannot be solved by science fiction or fantasy as we know them. He is not looking for a fiction of a whole different world; he wants a novel for this one. He desires an uncanny novel: one that evokes not the supernatural but the unthinkable—the narratively intolerable—reality of nature. He wants a novel that breaks its own rules, that understands the numbers and dodges them, that slips out from under the domination of probability. He wants a literature that creates a new reading experience, transforming the relationship between the quotidian and the code.

My terms are beginning to fail. I see that the quotidian, if it’s truly the experience of the everyday, has to include disaster. I see that the code, if it’s preserved in long-term memory, if it is in fact a code, is on the side of probability. So write me a novel there, where the terms fail. Write me a novel of this planet that isn’t topical, a novel that’s more than noise. The bourgeois novel may be obsolete; the quotidian is not. Rescue the everyday from the clutches of the plausible.

Rescue the code. Work the space between gradual and catastrophic time. Write me a fantasy that doesn’t produce the fiction of a totality. Write me the uncanny kitchen, the porch volcanic. Write me a science-fiction novel of short-term memory and of the flesh. Write me space-time in scattered notes. Make room for the transformed Delhi street of Amitav Ghosh: “In the dim glow that was shining down from above, I saw an extraordinary panoply of objects flying past—bicycles, scooters, lampposts, sheets of corrugated iron, even entire tea stalls.” Write me that dim glow: the weather, the wind, the change, the historical fracture, the glitch that revises all the probabilities. Don’t write me a novel about mutation, but write me a mutated, monstrous novel, the ghost story of your DNA, a book that a plant could read.

Be my accident. Prick me, bruise me a novel.

Sofia Samatar is the author of five books, most recently the memoir The White Mosque, published in October by Catapult. Her works include the World Fantasy Award-winning A Stranger in Olondria (Small Beer Press, 2013) and Monster Portraits (Rose Metal Press, 2018) a collaboration with her brother, the artist Del Samatar. She lives in Virginia and teaches at James Madison University.

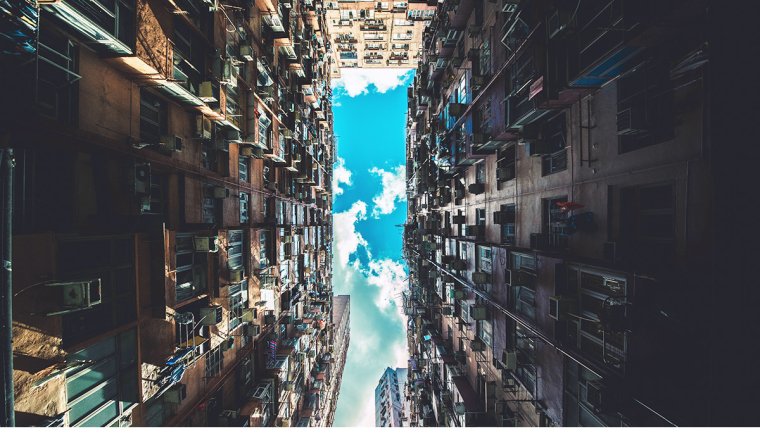

Art: Rikki Chan