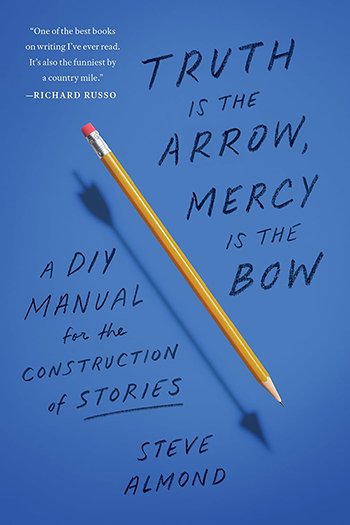

Three decades of writing and teaching culminate in Truth Is the Arrow, Mercy Is the Bow: A DIY Manual for the Construction of Stories (Zando), a new craft book by Steve Almond, the author of a dozen books of fiction and nonfiction, including All the Secrets of the World (Zando, 2022) and the New York Times best-seller Against Football: One Fan’s Reluctant Manifesto (Melville House, 2014). With chapters dedicated to the basics—plot, character, chronology—the book makes space to interrogate “the comic impulse” and “obsession” as well as the more personal, intangible aspects of writing. Which feeling is stronger: your urge to tell the truth or your fear of the consequences? How can you write “egoless prose”? To answer questions like these, Almond layers anecdotes from his childhood alongside his experiences with writer’s block and his observations of students. In his candid, nonmoralizing style, Almond examines writing from all angles, breathing new life into stereotypes about the writing process and the interior life of the storyteller. Below is the title essay from the book, “Truth Is the Arrow, Mercy Is the Bow: How to Write the Unbearable Story.”

Truth Is the Arrow: Mercy Is the Bow: A DIY Manual for the Construction of Stories (Zando, April 2024) by Steve Almond

![]()

When I was ten, my parents shipped me and my brothers off to stay with a babysitter for the weekend. They did this every few months, because we fought a lot. The babysitter’s name was Kay Brennan. She drove us south an hour, in her rumbling Barracuda, to Hollister, California, where she lived with a pack of unruly Belgian sheep dogs. Kay smoked menthols and listened to a lot of Stevie Nicks. There wasn’t much for us to do in Hollister. Our go-to activity was to whack clods of dirt with an aluminum baseball bat in the empty field behind Kay’s bungalow. We loved the impact, the ping of the pebbles in those clods.

One morning, it was my turn with the bat. My older brother Dave was standing behind me. I knew this. I had been warned. I reared back anyway. I’ve never forgotten the sensation of that bat striking my brother’s face, the spongy crack of it, the red geyser of his mouth.

I worshipped my older brother. I would have done anything for the least scrap of his praise. But he was often cruel toward me. That’s why I swung the bat. I carried this version of the story around for decades, composing a series of mawkish poems in commemoration, one of which, eventually, I sent along to Dave. I was hoping for absolution, obviously.

A week later, Dave called to tell me I had gotten the story all wrong. He had known I was swinging the bat and been told to back off repeatedly. Dave’s testimony is that he stepped into the path of my swing. Some part of him felt guilty for how mean he was to me. This was the punishment he chose.

Who can say, in the end, which version is the truth?

The truth is the blood.

The truth is the scar that still marks Dave’s upper lip, a pale crescent.

![]()

I often tell this story to writing students, in an effort to distinguish between fiction and creative nonfiction. The latter, I tell them, is a radically subjective version of events that objectively took place. You’re allowed to make things up, but we have a name for that. It’s called fiction. You have to be honest with the reader about the nature of your work.

But there’s another way to frame this story: as an act of seizure. What I’m doing, after all, is seizing the right to share with the world my version of this episode, in which Dave plays the guilt-ridden bully to my spurned younger sibling. My parents come off as negligent. And there’s Kay Brennan, puffing on a Kool, smelling of dog. By assuming the right to narrate, I become the boss, the final arbiter of our family history. If anyone else were doing the telling, it would be a different story.

It’s no surprise I assumed this role. I’m a white guy who grew up in a middle-class home with two loving parents who may have taken the odd weekend off but nurtured all their children and made them feel seen and heard. Beyond the confines of our home, I’ve moved through a world that has been sending me the message, every day and in a million different ways, that my story matters and that I have every right to tell it.

But now imagine—perhaps you don’t have to—that you were born in a female body, a body of color, an immigrant body, a disabled body, a body reared in poverty, a gay body, a trans body, a neurodiverse body. Imagine moving through a world that regards your voice as marginal, defective, or even dangerous, a world indifferent to, or outright hostile toward, the story you might want to tell.

Imagine you were born into a family with only one parent, or no biological parents. Imagine coming of age in a family haunted by divorce, trauma, addiction, mental illness, incarceration. Imagine a home marked by emotional violence, or physical violence, or sexual abuse. Imagine the internalized sense of shame and secrecy.

Every family enforces its own codes of silence. And every writer is, in this sense, violating some kind of omertà. But the scale of these prohibitions operates on an inverse relationship. The greater the resistance to the telling of a particular story, the greater the value in its being told.

![]()

I’m thinking now of the student I met a few years ago, at a writing conference in Florida. She was a junior in college, majoring in business if I’m remembering right, a beautiful, nervous young woman who took a creative writing class as her elective and had thus been roped into a manuscript consultation with me.

She had written a comic essay about getting her hair styled as a girl at a cut-rate salon. This was a big deal to her parents, who didn’t have a lot of money and who recognized their daughter’s beauty as vital to her prospects. I won’t go into details here, because the story is ultimately hers to tell. But I will say that glints of despair kept showing through her antic descriptions, moments when this grooming ritual sounded more like torture.

I didn’t say any of this to her. Mostly, I stuck to line edits. But I did make one comment of a personal nature. “It seems like there was a lot of pressure on you to be perfect.”

At this, the young woman, whom I had met only a few minutes earlier, whose hair looked worthy of a shampoo commercial, began to weep in quiet convulsions.

This is what I’ve witnessed as a teacher, over and over. People come to writing as a way of going in search of themselves. They are trying to process volatile feelings that went unexpressed in their families of origin, to revisit unresolved traumas. They are writing about what they can’t get rid of by other means.

This is not to discount an ecstatic devotion to language, or the transformative powers of imagination. But I’m talking about motives.

Herein lies the question every writer faces, at some level: Is my compulsion to tell the truth stronger than my fear of the consequences?

![]()

What most writers do is disguise the truth. Some use the comic impulse to defang their pain, like the young woman I met in Florida. Others decide, rather abruptly, to convert their memoirs into novels, which they hope will grant them distance and plausible deniability. Fiction writers frisk the world for symbolic versions of their experience.

Years ago, for instance, I went to visit an old friend in Maine. I wanted to meet his newborn daughter, and to offer condolences for his mother, who had died a few months earlier. My friend greeted me at the door and introduced me to his father, who was hovering near the kitchen island. I expected to make a little small talk before proceeding to the baby, whom I could see in the next room, curled on her mother’s lap.

But when my friend’s father learned that I was an adjunct professor, he launched into an odd reminiscence. Years ago, when he was an adjunct, the president of his university had called him late one night to tell him that one of his students had been killed in a car accident. They needed to notify the next of kin. Would he be willing to identify the body?

I could understand why a widower’s thoughts would drift toward a death memory. But it struck me that he was also nervous, uncertain how to connect with his family in the absence of his wife. When I got home, I sat down at the keyboard. In a matter of hours, I had written my version of the episode, changing a few details but remaining faithful to its essence.

Some years later, this story found its way into in my debut collection. My father wrote me a kind letter about that book, graciously ignoring its pornographic content. He reserved special comment for the story about the widower, the one I’ve been telling you about. “I never realized I was so emotionally distant as a father,” he wrote.

I remember rearing back from the page in alarm. I wanted to call him immediately, to correct the record: Wait a sec, Dad, that story’s not about...

But of course it was. That’s why it had snagged in my mind, why the fictionalized version had come reeling out of me. I’d felt too guilty, and too loyal, to write about this version of my dad, so my unconscious had latched on to a story that did the dirty work for me.

That’s how it works with fiction: Our inventions are veiled confessions. Our job isn’t to figure out why we’re writing a particular story. It’s to trust our impulses and associations, to pay attention to our attention.

![]()

The reason you sit down to write any story—beyond your ego needs—is because you want to tell the truth about some part of your life that haunts you. If the story is any good, you’re going to reach places of distress and bewilderment. You’re going to name names, shatter silences, wake some ghosts. There’s a lot of exposure involved. And thus, a lot of ambivalence.

Writing is an attention racket. But it’s also a forgiveness racket. The best way to keep going when the anxiety of exposure strikes is to remember that your goal is to forgive everyone involved, yourself foremost. A great story, of whatever sort, is not a monument to sorrow or destruction. It is a precise accounting of the many ways in which our love gets distorted, a secular expression of spiritual forbearance.

Many years ago, I got invited to the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. It was my first big jamboree and I’m sure I strutted around making a fool of myself. But the only thing I really remember of that conference is Barry Hannah’s reading.

I was a devout fan. “My head’s burning off and I got a heart about to bust out of my ribs.” That was the first line of his I ever read, and I never looked back. I read his collection Airships chronically, and though his stories were loose and Southern and baroque (nothing like mine), they had helped me come out of the closet as an emotionalist.

Folks at Sewanee still loved to tell tales about Barry’s wild days. But he was into his sixties by then, slowed by cancer, soft-spoken, even shy, and leathery as a lizard, with a deep croaking voice that made all his words sound as if they came from the pulpit.

I can’t remember the story he read, only that it involved a friend of the narrator’s getting into some kind of fatal mayhem. What I do remember is how Barry paused, toward the end of the piece, and how we in the audience, after a few moments of confusion, recognized what was happening, that Barry Hannah was weeping, that the memory of his friend, and of his friend’s death, had overtaken him.

“I’m sorry,” he said quietly, touching at a tear on his cheek. “I didn’t realize all that would come up.”

It was a profound moment for me, because, like many of his readers, I hadn’t really grasped that there was an actual person behind the authorial persona (Barry the Drinker, the Madman, the Legend). He wasn’t just dreaming up escapades in some haze of whiskey and genius. He was writing about the people he had lost.

Barry himself was, I’m sure, quite embarrassed. But there was nothing he could have read, or taught us, that would have delivered the message more plainly: your job as a writer is to love and to mourn, to tell the unbearable story so that others might feel less alone in theirs.

![]()

All of which sounds excruciatingly noble. But it’s hard to hold on to when your story involves a violent partner, a sexual assault, a murderous impulse toward a child.

Or how about an abusive parent? To write truthfully about such a figure is to wrench open a portal of pain. Rather than healing a rift, the act of writing—regardless of genre—can reopen old wounds. And that’s what often happens, frankly, at least in initial drafts.

I recently read a memoir by a student whose adoptive mother was a genuinely destructive force, negligent and controlling, verbally mocking and physically menacing.

But there were aspects of this mother’s history—briefly noted—that struck me as vital. She had been raised in an aristocratic family, primarily by servants, with no real sense of maternal attachment. A violent revolution forced her family to move when she was young, and they lost their fortune. She married for love, against her family’s wishes, and her husband promptly moved her halfway across the world to a small town in the United States. She couldn’t speak English and had no support. So she sat alone in a dim apartment, while her husband pursued his career. Then she discovered that she couldn’t conceive children, a source of extreme shame in her culture. Long before she adopted children, she was battling profound mental health issues, which went untreated and thus drove her deeper into isolation.

None of this context excuses the cruelty inflicted on her daughter. But taken together—truly acknowledged, that is— these facts allow us to reckon with the author’s mother as someone whose cruelty arose from despair. Instead, the memoir was dominated by scenes of maternal tyranny.

Vengeance is a natural impulse when you relate the story of a damaging figure in your life. But the reader always sniffs it out. It’s the difference between an indictment and a trial, between a rant and a lamentation. When I’m telling stories of this kind, I always try to challenge my instincts, to adopt the perspective of my antagonists, to complicate my version. I try to figure out if my criticisms are a form of projection. That is, if I’m angry at someone else because I’m guilty of the same transgression.

Claiming the role of storyteller doesn’t give us a franchise on the truth. Indeed, it may trigger feelings of grandiosity that flatten out those around us. Most difficult of all, we have to tell the parts of the story that we are most apt to hide, even from ourselves: that our antagonist was sometimes kind and even tender to us, that we once clung to them with a fierce loyalty, that they proved too weak and damaged to protect us, that beneath all the swirling rancor is an ache that binds us together.

It is, of course, unrealistic to expect a traumatized child to summon forgiveness toward an abusive parent. But the writer’s task as an adult, looking back on those wounding events, is to tell the whole truth, and that pursuit is doomed without forgiveness. The more mercy you can summon, the deeper you will travel into truth.

![]()

For many years I was reluctant to tell my girlfriends I was in love with them. I viewed love as a code word for certain emotional promises I had little hope of keeping, and therefore made the typically scuzzy masculine argument that “love” was an arbitrary threshold, who really knew what it meant, and what mattered was how I behaved, not the terms affixed to those behaviors. This was the part of the story just before I got dumped.

I still think of love as a fuzzy word. But as a storyteller, I’ve come to see love in more precise terms, as an act of sustained attention implying eventual mercy. There is nothing more disheartening to me than a story in which the writer expresses contempt for his characters. It’s the one posture I can’t abide, because it amounts to a conscious rejection of art, whose first and final mission is the transmission of love.

That’s what’s happening when you read any great piece of writing: the love transmitted from the author to her characters is being transmitted to you, the reader. This is why I exhort students to love their characters at all times.

I don’t mean by this that you should coddle them. On the contrary, it is your sworn duty, as a fiction writer, to send your characters barreling into danger. And, as a nonfiction writer, to witness and interrogate their darkest deeds. Nor do I mean to endorse some bland form of moral absolution. I mean something more much like what the authors of the New Testament ascribe to Jesus Christ. That you love people not for their strength and nobility but, on the contrary, for their weakness and iniquity. Your job is not to burnish the saint but to redeem the sinner.

I want to emphasize this because certain agents and editors stress that characters should be likable, which, along with its ditzy cousin relatable, is one of those marketing words that has infiltrated publishing. (Thanks, capitalism!)

I implore you not to think of your characters in this way. Your job is to reveal them as they are, not to charm the audience. It is both fraudulent and deeply condescending to assume that readers will turn away at the first disturbing utterance or action from your heroine.

To me, the appearance of a “likable” character triggers the same exhausted skepticism with which I greet certain social media posts, the ones where everyone is smiling and the food is backlit. Such airbrushed displays offer me nothing to participate in, other than envy.

![]()

Back in 2014, Claire Messud published The Woman Upstairs. The heroine, a forty-year-old teacher named Nora Eldridge, has retreated from her creative ambitions into a life of stifled duty. The novel is an epic rant, delivered by a woman angry enough to “set the world on fire.”

While promoting the book, Messud was interviewed by a young female critic, who asked her a rather loaded question: “I wouldn’t want to be friends with Nora, would you? Her outlook is almost unbearably grim.”

“For heaven’s sake, what kind of question is that?” Messud responded. She went on to catalogue the many despicable leading men in our canon, before adding: “If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble. We read to find life, in all its possibilities. The relevant question isn’t ‘Is this a potential friend for me?’ but ‘Is this character alive?’”

Characters such as Nora refuse to be stuffed in an attic or kept silent any longer. (I’m thinking, too, of Antoinette from Wide Sargasso Sea, and her final declaration, before she burns Thornfield to the ground: “Then I turned round and saw the sky. It was red and all my life was in it.”)

For the record, Nora’s outlook isn’t unbearably grim. It’s unbearably honest. She’s furious at the lost promise of feminism, but also at her own acquiescence. “I always thought I’d get farther,” she confesses. “I’d like to blame the world for what I’ve failed to do, but the failure—the failure that sometimes washes over me as anger, makes me so angry I could spit—is all mine, in the end.” She goes on, “Isn’t that always the way, that at the heart of the fire is a frozen kernel of sorrow that the fire is trying—valiantly, fruitlessly—to eradicate.”

The Woman Upstairs is a stark example of the work literature is meant to do, which is to implicate the reader, to bring them into contact with the damaged precincts of their inner life, to help them feel less isolated with those parts of themselves. Big emotions are disruptive to our lives off the page, which is why we expend so much energy hiding our sadness, suppressing our rage, dodging conflict, striving to be likable.

As writers, we have to accept a different code of conduct. Our mission is to aim for the painful events and unresolved feelings, to spend time amid desperate characters, to push past our inhibitions. It takes work for us to find a voice capable of such courage.

Vivian Gornick writes about the process as a form of liberation. For years, she sought a narrator who could tell the truth as she alone could not. “I longed each day to meet again with her. It was not only that I admired her style, her generosity, her detachment (such a respite from the me that was me); she had become the instrument of my illumination.”

It is my own sentimental belief that writers justify what we do by exhibiting superhuman compassion in the face of persistent misbehavior. Our books are the written record of that compassion, but they shouldn’t be confused with our lives. Off the page, I am often a shithead: insecure, controlling, tiresome. Just ask my wife.

That’s the ultimate dividend of writing: You get to be a better person on the page than you are the rest of the time. More merciful and therefore more honest.

![]()

Writers find a lot of excuses to avoid exposure, especially early in our careers, especially if we’ve been told to remain quiet. One way is by leaping ahead to the part of the story where we’re already published and everyone is mad at us. But exposure is something that’s incremental, something we get to control.

Setting down an unbearable story in a private draft isn’t the same as submitting it to a workshop, or publishing it, or showing it to a beloved. Those acts are further downstream. Self-assertion comes first.

I experienced this for four years, as the cohost of the Dear Sugars podcast. My friend Cheryl Strayed and I received thousands of letters from people in crisis, as many as a dozen a day. Very few of our correspondents were writers. But Cheryl and I were struck by the sheer, unflinching beauty of the prose.

We could see the precise spots where the stories faltered, where the author descended into self-pity or contempt or fraudulence, where a deficit of mercy kept them from reaching some agonizing final truth. That was where we came in, I guess.

Most of what we told our listeners they knew already. They knew they needed to set a boundary. They knew love was supposed to feel safe. They knew it was time to leave. What they needed, most of the time, wasn’t wisdom, but permission. We might have helped around the margins, but Cheryl and I weren’t even the crucial part of the equation. It was the very act of composing and sending those letters—of granting themselves the right to tell their own story—that was healing.

What we’re really afraid of is facing the truth, living in the pain and confusion of it. But grace arrives only when you’re standing in the truth.

![]()

I’ve written this essay so many times. I keep finding reasons to cut the story I told you at the beginning, the one about hitting my brother Dave in the face with a baseball bat. It makes my childhood—which was one of extraordinary privilege and relative safety—sound dangerous, and therefore sensational. It’s not even something that happened to me.

So out it went.

Then I put it back again.

Why?

Because, I think, some part of me is still ten years old, in that dirt field in Hollister, still in love with my big brother, still angry at him for not loving me back. Maybe by telling the story I get to smash Dave all over again, this time for a bunch of strangers.

Or maybe the truth is even worse, because I know what comes next, all the ways in which Dave struggles later on, succumbs to the bad chemistry coursing through him, calls me with his brain on fire, from somewhere beyond the reach of my good fortune, muttering strange theories, quoting the haunted movies of our youth, repeating himself, falling short of the God I still need him to be. Maybe I’m still trying to take the blame for those struggles.

I haven’t figured it out.

I only know that Dave and I have managed, after many years of estrangement, to find a path back to one another. We’re both the worse for wear, often exhausted, but also properly humbled, able to be kind in a way that once felt impossible. It has been one of the great honors of my life to help reinvent our brotherhood, to call him a friend.

Once upon a time there were two brothers who could be intimate only through an act of violence. I don’t want to go back there. But I still remember how it felt the old way: the weight of that bat, the spongy crack. It’s fine to be scared, maybe even necessary. The path to the truth runs through shame but ends in mercy. We’ve all got work to do.

From Truth Is the Arrow: Mercy Is the Bow: A DIY Manual for the Construction of Stories by Steve Almond. Copyright © 2024 by Steve Almond. Used by permission of Zando. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Steve Almond is the author of twelve books of fiction and nonfiction, including the New York Times best-sellers Candyfreak and Against Football. His recent books include the novel All the Secrets of the World, which has been optioned for television by 20th Century Fox, and William Stoner and the Battle for the Inner Life. For four years, Steve hosted the New York Times Dear Sugars podcast with Cheryl Strayed. He is the recipient of a 2022 NEA grant in fiction, and his short stories have been anthologized in the Best American Short Stories, the Pushcart Prize, Best American Erotica, and Best American Mysteries series.