Last summer, University of Oxford professor Matthew Reynolds, in collaboration with an international team of more than two dozen scholars, launched Prismatic Jane Eyre, a research project that explores the relationship between Charlotte Brontë’s classic 1847 novel and its many translated versions. In comparing the hundreds of translations that have been made across the globe in the more than 150 years since the book’s publication, Reynolds and his team hope to better understand the way a source text is read, absorbed, and transformed by translators, and the ways these translations reflect the culture in which they were created.

The project grew out of Reynolds’s wish to do a “collaborative, comparative close reading of several translations in different languages,” he says. This idea soon led to questions about the larger context of those translations and what other translations existed in the world. Reynolds says he decided to focus on Jane Eyre “because its internal conflicts seemed likely to play out differently in different cultures, because it is a popular as well as a literary text, and also because translation has a role within the book.”

In the project’s first phase, a team led by Oxford postdoctoral researcher Eleni Philippou spent the past two years tracking down every single translation of Jane Eyre since its initial publication. They unearthed a total of 594 different translations into fifty-seven languages, including Irinarkh Vvedenskiĭ’s colloquial Russian translation from 1849, Amır Mas‘ūd Barzīn’s 1950 Persian translation that he abridged by omitting subjects “not interesting to the Persian reader,” Yu Jonghos 유 종호’s 2004 revision of his 1970 Korean translation that substituted the former’s ornate Chinese vocabulary for more modern Korean language, and Amal Omar Baseem al-Rifayii’s translation from 2014, the only known Arabic version by a female translator.

A series of interactive world maps on the project’s website (prismaticjaneeyre.org) illustrate the scope and range of these many iterations, pinpointing each translation’s city of publication and noting its language, date, and translator. In this and other ways, the project emphasizes the individuality of translators, although, Reynolds says, “Usually all that is known of a translator is a name and often not even that—about 15 percent of the translators are anonymous, and an unknown number are pseudonymous.” The map’s color-coded display helps to illustrate where translations have proliferated. The website also features a time map through which users can trace the chronology of the translations, noting patterns or waves of popularity. For example, Jane Eyre was translated into Persian thirty times after 1950. “It was a surprise to discover how much those visualizations change one’s sense of where the book belongs,” Reynolds says.

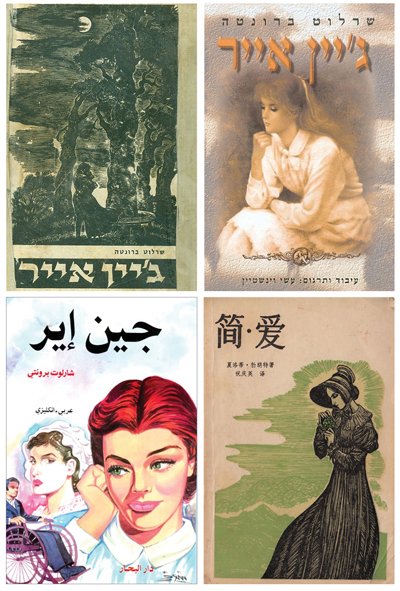

During the project’s second phase, to be rolled out this spring or early summer, the team will compare the language used in about twenty-five of the translation languages. For instance, different translations of the title—originally Jane Eyre: An Autobiography in English—highlight different interpretations of the book’s themes. Titles such as 简爱 Jianai [Jane Eyre/Simple Love] in Chinese, and Jane Eyre: Yıllar Sonra Gelen Mutluluk [Jane Eyre: Happiness Coming After Many Years] in Turkish emphasize the book as a love story, while titles such as Kapag bigo na ang lahat: hango sa Jane Eyre [When Everything Fails: A Novel of Jane Eyre] in Tagalog, and Yatim یتیم; subtitled ژن ئر [Orphan: Jane Eyre] in Farsi might point more toward social issues. The team will also explore patterns in the translation of the book’s key words and phrases. The words plain and passion, for example, are repeated throughout the original novel to describe the protagonist; both have been translated in endless ways, in accordance with the translator’s readings of Jane’s temperament, and exemplify the ways narrative style can reveal a culture’s values. In the third phase of the project, scholars will use digital tools, including one that measures the uniqueness of words in a passage of text, to analyze how style shifts and stretches across different languages—a glimpse of how technology may contribute to the future study of literary translation.

Reynolds and his collaborators hope the public will add to their understanding of the diversity of Jane Eyre’s translations. The team invites the public to alert them to missing translations, contribute personal translations of passages, and submit reflections, discoveries, observations, and theories. As the project proceeds, the Prismatic Jane Eyre website will be updated with findings, blog reports, and interactive features. In its fourth phase, in 2021, the project will publish a comprehensive volume of research, analysis, and essays, which will include a complete list of all the translations.

Prismatic Jane Eyre is part of a larger Prismatic Translation project, hosted by the Oxford Comparative Criticism and Translation Research Centre, whose scholarship revolves around a set of theoretical stances on translation: “Translation is creative, not mechanical; it is a matter of growth as much as, or more than, loss. Translators are writers. Languages are not separate boxes but are rather intermingled areas on the ever-shifting continuum of language variation.” This attitude departs from historically conventional perspectives of translators as secondary or unoriginal. It also rejects the notion that translation takes place between discretely bounded languages and suggests instead that those boundaries are fluid and permeable. Reynolds hopes Prismatic Jane Eyre will further advance these ideas. “One of the main ideas driving the project is that everyone reads differently, and uses language differently, and that those differences are interesting,” he says. “The key thing in thinking about translation is not to reify standardized national languages but rather to recognize the great variety of textures and structures that language is made up of and the variability of the terrain that translation works across.”

Bonnie Chau is the associate web editor of Poets & Writers, Inc.