In this, our sixth annual feature on authors whose first books arrived a little later on what we are often led to believe is the timeline for a debut author, we reaffirm our stance on the notion that youth is a bellwether of literary excellence: It is time to reset the clock. Better yet, let’s just throw the clock away. It is well past time to stop using “new and emerging” as a synonym for “young,” to stop considering age as some kind of helpful gauge of new literary talent. Instead, we should marvel at the countless different routes writers take on their way to publication, such as the ones traveled by this year’s 5 Over 50, including seventy-one-year-old debut author Vinod Busjeet, who reminds us that “you’re never too old to publish that debut novel.”

Here are excerpts from the debut books by this year’s 5 Over 50.

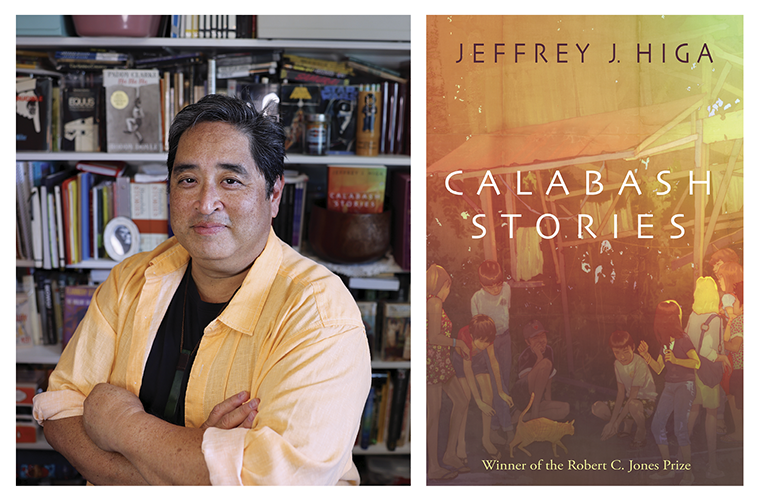

Calabash Stories (Pleiades Press, April 2021) by Jeffrey J. Higa

An Indian Among los Indígenas (Heyday Books, April 2021) by Ursula Pike

The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child's Memory Book (Mad Creek Books/Ohio State University Press, May 2021) by Megan Culhane Galbraith

Wordly Things (Milkweed Editions, June 2021) by Michael Kleber-Diggs

Silent Winds, Dry Seas (Doubleday, August 2021) by Vinod Busjeet

Jeffrey J. Higa, author of Calabash Stories published in April by Pleiades Press.

The Shadow Artist

The Shadow Artist knew himself to be a relic. A walking anachronism in the forgotten uniform of his profession: the black top hat, the formal doublet and waistcoat, the black bowtie. He knew the cartoonish figure he cut, a wandering aristocrat dragged from the previous century, traveling the red dirt roads from sugar plantation to sugar plantation in West Oahu. And yet, all of this—his clothing, his art, his manner—he assumed with a solemnity bordering on the sacred, as if his very existence were some kind of offering to a deity long discredited. This reverence silenced those who might ridicule him, and instead, they looked on in silent curiosity, stopped in the midst of their activities, waiting for him to pass before restarting the sweep of their lives.

He had once made his rounds in the cooling heights of Mānoa, received at front doors and ushered into homes with the fuss due a visiting regent. Girls would don their finest dresses, mothers would slick back the hair of their unruly sons, even fathers would venture down in their Sunday best for a session with the Shadow Artist. He had used the finest French papers then, blanc et noir, ordered from a distributor in Tahiti, and after hanging the white sheets behind his subject, he would create shadow profiles from whatever illumination was available: candle, gas lamp, and later, electricity. He would then sit with the subject and talk with him or her for nearly an hour as he cut constantly, reducing the white life-sized outlines smaller and smaller until the very last minute, when he slipped a black sheet under the white and cut the final portrait. In this way he had been different from his colleagues, competitors who boasted of their speed—“Portraits cut in under ten seconds! Families in under a minute!”—and relied on their flashing scissors and scraps of flying black paper for their drama. The Shadow Artist relied on the subtle drama of transformation, the movement from rough outlines to definitive portraits, from working white to final black. He allowed his subjects to talk about themselves, their words shaping changes to a line here, a minimizing of features there, until he revealed to them the silhouette that they themselves had always desired.

His colleagues had ridiculed him for it, for in their time, they could make more in fifteen minutes than he could make in a day, but here, now, it was this difference that made him the last. He watched them get squeezed out of the piers where the cruise ships docked, and replaced on the downtown street corners by dabblers in what would come to be known as photography. At first, the Shadow Artist believed that there would always be a place for his skills beside this new dirty science with its arcane processes, stinking chemicals, and exploding elements. But people seemed to clamor for these frozen moments of time, these portraits of merciless detail, so unlike his timeless silhouettes with details combed and edited over with an eye to eternity.

Now all he had left were his weekly appointments at the plantation death houses in the sugarcane fields of West Oahu. These sojourns, another relic from earlier times, were at the behest of the Japanese and Filipino labor unions who paid him a small remuneration for capturing the likenesses and personal histories of their valetudinary members. He mailed this information once a week to the unions, where, eventually, the information would be used in the obituary sections of the Filipino- and Japanese-language newspapers. The Shadow Artist did not know why he was still on the union payroll—even the newspapers would not print silhouettes anymore—but he figured that he was being tolerated out of pity, not unlike the pity shown to the residents of the death houses. These unmarried, family-less men who had worked themselves until they broke and had lost all of their money to whoring, gambling, and foolish investments had nowhere else to go and lived out the remainder of their lives in the communal charity of the death houses. As a younger man, the Shadow Artist had contemplated the death houses with a kind of superstitious dread, but now, nearly the same age as these residents, he approached them with almost an obscene comfort as the final witness to these men whispering out their lives without notice—a fitting metaphor, he felt, for how he and his art would go.

From Calabash Stories by Jeffrey J. Higa. Copyright © 2021 by Jeffrey J. Higa. Reprinted by permission of Pleiades Press.

Read Jeffrey J. Higa’s essay about writing Calabash Stories in the November/December 2021 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine.