When I read submissions, I try to say no as quickly as I can—because the most fun, and most time-consuming, part of my job is to say yes to a project I’m excited about. That could be because the writer has made something I didn’t know I cared about seem urgent or relevant, or demonstrated undeniable artistry, or shared some unique expertise on a subject of interest. Projects that I immediately connect with are rare, but they’re what editors live for.

Fishman: The hardest query to get is the average to just-above-average one, because you have to read the whole thing, thinking, “Well, maybe I can do something with this.” By the way, I think it’s okay to get rejected.

Ballard: Also, taste is incredibly subjective. We see things that we’ve passed on go on to sell all the time, but if you aren’t the person who believes in the book, you should not be selling it. And that’s the bottom line.

Flashman: The trick is, if you’re a writer, you don’t just want an agent who could sell it. You want an agent who must sell it. We all get query letters, and think, “Yeah, I could probably sell this.” But are you really the best agent for it?

Editors know the difference between the agents who represent whatever they think they can sell and the ones who are more selective.

Fishman: I think the easiest thing to do, in a lot of ways, is to sell a good book. Everything else is the hard part.

Ballard: I often take people on and then work with them for a very long time. The first novel I sold this year was something I had worked with the author on for four years. It wasn’t that I was editing every line. We just had to find out what the story was. I work very closely with my clients, and I bet everyone in this room does. The better you make the book, the better the sale.

Flashman: Your point is really important because sometimes writers think, “Oh, I’ve got an agent! We’re sending it out, it’s going to be a best-seller tomorrow!”

Habib: There’s a lot to be said for the long game. Look for an agent who’s in it for the long haul.

What has been most surprising to you since you became an agent?

Ballard: It’s surprising that the most beneficial thing for my long-term career was, in a funny way, to get promoted in 2008, right when the financial crash was happening. It felt like everything we knew about publishing was going to change dramatically. I remember some older agents bemoaning the fact that things used to sell more easily, that there was a guaranteed number of hardcover copies sold if you were paid a certain level advance. But all those guarantees went out the window. I don’t know if that’s a good thing or a bad thing. But I didn’t have any false expectations of what success would look like in the industry. I think that agents who came of age in the nineties experienced a very different business than what we’re experiencing right now.

Flashman: Another thing that’s surprising is the sales numbers. When you compare movie box office receipts to how many books you have to sell to hit the New York Times best-seller list—it’s pretty astonishing.

The best-selling books aren’t reporting millions of dollars of sales over a weekend like the top movies do.

Flashman: Right. And I’ve had books that end up in what I hear publishers call the “power backlist,” where they maybe hit the list once but then go on to sell and sell and sell just beneath that level. And sometimes the literary novel that you hear about everywhere and think will be a massive best-seller ends up selling four thousand copies.

Fishman: I think literary fiction in particular is a big echo chamber in New York. I represent a lot of literary fiction at different levels of success, and I love it. But when I send out a science fiction novel, I can send it to five, six people in a first round. I can send a literary novel to fifteen to twenty people. And you can pour your heart and soul into a literary novel and be shocked by how few sales there are. In other genres that have dedicated groups of followers, you may have less shelf space, but if you get on that shelf, you sell more copies at a minimum. Each genre has its own dynamic.

Flashman: Each industry is weighted to different sorts of backgrounds, too. One thing I realized pretty quickly when I got into publishing is that it’s heavily weighted to English majors. I love literary fiction, but I don’t ever worry that there aren’t going to be enough editors to buy literary fiction. I do worry about books about science and technology.

Fishman: I want to comment on what Claudia said a minute ago, because I came up in 2008 as well. A lot of people from my class—the people we were drinking with when we were starting—are all moving from publisher to publisher now. When you sell a book, you sell it to a house. The editor is the point person, but editors move quite a bit. That’s been a learning process for me. Now it’s not just “Are you the right editor for this book?” but also “Are you going to be around at this place when the book comes out?” In the last two years I’ve had eighteen orphaned books.

Habib: The last, like, five books I sold were orphaned.

Flashman: I’ve had books become best-sellers that were orphaned. Sometimes those books have even had three editors.

Ballard: You just want the house to carry on the enthusiasm of the original editor.

How do you conceive of a perfect match between author and editor?

Habib: A lot of us go to a lot of lunches with editors, and when I go out to lunch I want to get know the person. I hate talking about their list. I want to hear about the books they loved as a child. I want to hear about their dog. I want to hear about their quest to find the perfect preschool. Part of it is just matchmaking—some nebulous quality that helps give you a sense that an editor and an author will understand each other. That is, that the editor will understand the author—but also be able to crack the whip.

That’s important. I’ve been too close to a book before.

Ballard: I think that’s an interesting thing about our relationships with writers, both on the editorial and agenting sides. You have to feel close to the work, almost as close as the author, but never quite as close as they do. Because it’s not originating with you. It’s not your art. You’re art-adjacent. I come from this place of being a deeply sympathetic reader: Do I love reading this book? That, to me, is always the first indication of a match. And that registers in an editor’s first phone call to you, and that letter expressing their love for the book. The feeling in-house. It is this connection that has to really feel organic and real and based in a deep reading of the book.

Habib: Some writers think that an agent can somehow convince publishers to buy their book, just by their sheer charisma and personality and power. The real thing we do is find the most sympathetic reader for the book, the editor who will best help the writer. I’m not going to convince someone your book is good. That’s your job. I can convince them to read it, and I can help make it the best book possible, but my job is to find the best reader for you.

Fishman: We build lists over a long period of time, and people pay attention to your track record. There’s also another level that we mess around with, which is our experience. Every day we work with someone, we find out whether we want to work with them again.

So, do editors still edit?

Fishman: Yes!

Habib: Of course!

Ballard: Yes!

Flashman: And we know who edits more.

Do you mean there are editors who don’t give their all to a book?

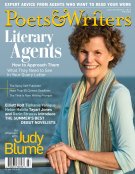

Flashman: Well, there are editors who buy books that don’t need very much editing. Sometimes that’s just a whole different business. They might be books that have outside editors or ghostwriters on them, so there’s a lot of editorial processes happening before it ever gets to the editor. And they’re in the business of making a certain kind of hit at a publishing house. But editors totally edit, Poets & Writers readers!

Fishman: There are some editors who are better cheerleaders than other editors in-house, which is totally different. They all edit, but in addition to good editorial vision, I’m looking for the editor who has the muscle and excitement to get something happening in house.

Habib: One of the things I was surprised by when I moved over to the agenting side was the skepticism a lot of first-time writers have about publishers. They’ve heard all these horror stories, so they think editors don’t edit. They think publicists don’t care. They have this hierarchy of who’s good: Publicists are the lowest, then editors, and then agents. The writer trusts the agent to find them a good home. I want to believe that all of us do that in good faith, knowing that editors do edit. Ideally, the publicity and marketing department will do their best job, and if they’re not, we try to help them, and to be there, and to be honest about when it’s not happening.

Flashman: If editors wanted to make a lot of money, they would have gone into another business. The people who work in publishing love books. They really want to make it happen. They love to edit. I think most editors wish they had more time in the office to edit because they’re doing a thousand other things.

What qualities do you try to bring into your own practice as an agent?

Ballard: I think that the people who’ve lasted in the business are the people who conduct themselves in an honorable way and are deeply passionate and incredibly knowledgeable about their field of interest. It’s meaningful to say that we all do what we love, and that you see agents who have achieved a lot of success in the industry who really love and care about it. When I first started out in the business, I thought for sure I was going to be an editor, just because I was an English major. I didn’t realize how much editing happens on the agenting side, or how much I valued the kind of personal relationship you have with your writers.

Flashman: I think we’re somewhere between a shrink and Karl Rove. Nothing about my politics, but there’s a lot of strategy and a lot of psychology.

Fishman: Yeah. I don’t know if writers realize how collaborative being an agent can be, especially within an agency, because we really do work together.

When do you feel competitive with other agents?

Flashman: When we’re competing for the same project! Which we often are.

Habib: I never ask who else is offering to represent a book.

Flashman: I don’t either, but some agents do. I don’t want to know.

Ballard: I tend not to ask until the very end, or right when I sign the person. I’m curious. We’re inherently competitive, and I think you want a competitive agent because she is going to be that way for you no matter what situation you face.

Fishman: I don’t want a book to go to Claudia when I competed against her for it. Heartbreaking stuff.

Ballard: But also, if Seth wins something over me, it’s a sign that it was a good book.

Flashman: You’re like, “I was right!”

Ballard: “I cared about this, but at least I lost it to someone whose taste I really respect and feels similar to mine.”

Flashman: And if you lose it to someone who you don’t respect, you’re like, “Oh, that writer is just making bad choices.”

Fishman: That’s true!

Ballard: Look, I would rather be in the mix and lose than not be in the mix at all.

Fishman: Every once in a while there’s an author who leaves his or her agent for some reason, and I didn’t even know, because I don’t want to poach. I don’t want to be an aggressive person.

Ballard: And sometimes you’re going to lose something just because it just goes more quickly than you can read it. That’s because we’re busy human beings. We’re not reading machines. We have, hopefully, rich lives outside of work where we have families and friends and hobbies and pastimes.

That’s not so different from competing for a book as an editor.

Ballard: The problem is that the decision isn’t based on money, so when we do lose, it’s all personal.

True—but as an editor, if you lose to an underbidder, it’s even worse!

Ballard: Then you can take it personally!

Fishman: I’ve done that twice.

Flashman: I’ve had someone take a lower advance…maybe never?

Habib: Oh, I’ve had that happen a couple times.

Comments

davgam007 replied on Permalink

Interview with four literary agents

Thank you, Michael Szczerban, for that very informative interview. I have seen and experienced all that you have described based on the interviews you had with the four litereary agents, and am greatful for the opportunity to have had Poets and Writers send me their monthly E-newsletter. I always read them. I am a self-published author and am constantly working on improving my writings. It is not an easy thing, but I love it. I participate in the Poets and Writers yearly "Round Table" meetings at the Riverside, Ca. Library each year for the past four years. I have also been a member of the California Writers Club, Inland Empire Branch, for the past ten years. And although I am not, yet, a well known writer, I did, however, recently give a talk at Valley College San Bernardino, a community college in my area, on self-publishing and what to expect after having written that book. I am glad to say that I covered most of what the agents had to say about the writing world today. Things certainly have changed. I'm hoping that more writers have that knowlegde and share it with those wanting to know. Thank You Once Again. Dave Gamboa.

thebestdigger@a... replied on Permalink

Amazing Interviiew

When I began the read, I thought, Ohhh, they are so young looking. By page 2 I said, Wow! They work so hard, care so much, know their craft, their trade! I'm not sure you can really know how great a peek into the working life of these dedicated people can be. Thank you so very much, Michael Szczerban, for this necessary information so few writers ever experience.

My anxiety re the writer/agent experience is greatly reduced, my fear of messing up a query better managed, less terrifying, and my confidence pushed higher to trust an agent to truly care about what matters so much to me.

Writing from my own experience with orphanage and post WWII, allows me to impart authentic story, and I thank you, Habib, for framing that value for me. The four of you did a fine job of articulating what is such deep mystery to so many writers, sort of lifting the veil and showing us that agents, editors, publishers are real people with real jobs and real interest in constituting really good stories well told.

Having just finished my memoir...Mama Was a Boom-Boom Girl in WWII...I am about to embark on all that you have talked about. The four of you are true assets to the literary world. Poets and Writers has done us all a great service.

Having just finished my memoir... Mama Was a Boom-Boom Girl In WWII...I am about to embark on all that you've talked about, necessary knowledge writers need. Timely, indeed. I can't thank you enough for your thoughtful responses. The four of you are true assets to the literary world. Poets and Writers have done us all a great service.

inframan replied on Permalink

Where have the grown-ups gone?

Not sure I'd have a whole lot of confidence in agents who hold the correct spelling of their name (or gender assigment) among the major criteria for assessing an ms. If Fitzgerald or Hemingway (or Carver or Cheever) had been sloppy spellers where would the (American) literary world be today. Also don't get a sense of much wisdom or a lived-in life being present in the group. Where are the Mitchells & Maxwell of today. Has publishing become a social media-based lemonade stand?