How long were you at Goldman?

A little more than two years. It was a long two years. They were long days.

What were some moments when you were really excited to be there?

First of all, having the opportunity to work with people who are that smart about what they do is incredibly exciting. If investment banking had been my passion, I could not have picked a better firm than Goldman. As it turned out, it was not my life’s passion.

Look, at twenty-two you’re in the room with CEOs of major companies, talking at the highest level about corporate strategy or creating shareholder value. That’s a surreal and pretty interesting opportunity. I don’t even think I realized how lucky I was to be there and to be in those rooms and to have access to those minds, because I wasn’t passionate about it. In fact, I’m much more interested now in deploying the skill set I was building then than I was at the time.

I was so overwhelmed by how much there was to learn and how few hours there were in the day that I didn’t stop to think about the things that I have the perspective to tell you now. I also was frustrated by the fact that I knew immediately that I was on the wrong side of the business, so I spent a lot of my time there wishing I were somewhere else.

How did you make the decision to leave?

I went in thinking I would do two years, which was the typical contract when you join straight out of college as an analyst, and then go back to law school or go work for a client. A lot of people did eventually transition to work for companies that had been clients of the firm. I never thought I would be a career banker. The question was always, What do I use this for?

Having spent some time in New York, were you ready for the West Coast?

I was thinking about it. I had spent a lot of time in LA, and I love it, but I wasn’t convinced at the end of my time at Goldman that I wanted to move there. I was fortunate that a couple of the people that I’d worked with on the client side did offer me positions. I would have thought that greenlighting movies would have been a dream job, but none of it felt exactly right, and neither did law school. I took some time off and went home to think about what the next thing should be, and found that I was spending a lot of time reading books.

Had you had been making time to read while you were an analyst?

Almost never. It’s not that I wasn’t making time; there really wasn’t any time. I could probably count on one hand the number of books I read that were not for work in the time that I was there. But reading one of them was very helpful to me in realizing just how ill suited to working in investment banking I was.

I was sitting out on the plaza one day, which didn’t happen very often, eating my lunch. It was a beautiful summer day. This must have been eighteen months into my two years there. I was reading a novel, and one of the managing directors from my group walked by and asked what it was. I held the book up and I said, “The Count of Monte Cristo.” And he looked very perplexed and said, “Why?” And I said, “Because I haven’t read it before.” He looked even more perplexed and walked off, I think, wondering why I was wasting my time in the middle of a workday. It underscored that I was interested in different things from most people I was surrounded by.

So you’re back at home, reading during your time off. What then?

I had never considered publishing as a business prior to that. In part it was just from ignorance. On the banking side, we did a lot of work with newspapers, but at the time, book publishing was pretty stable. Pearson had bought Penguin, but that had happened prior to my tenure. We did a lot of work in music and television and film and online content, but I hadn’t done any with book publishing. And because I had spent most of my four years in college reading books published prior to 1950, I didn’t have a good sense of what the publishing business was now, with one exception. In my senior year, I had one requirement left, which was an American literature survey course. We read American Pastoral. It was the first contemporary literary novel I had read in some time. It made me think that publishing today was more than commercial best-sellers, that people were still writing real literature. I love that book. And I love Philip Roth.

When, two and a half years later, I found myself spending all my time on novels, I thought: Maybe publishing? A lot of the clients I worked with at Goldman had publishing divisions. I was lucky enough to know some people and to say, “I’m thinking of getting into publishing. Is there anybody you could introduce me to?” I was able to go in for informational interviews with very senior people, and every single person I met with told me I should be an agent.

Why do you think they said that?

Well, I was neither twenty-two nor fresh out of college, and I was probably a little bit more aggressive and entrepreneurial than a lot of the people who walk in to both agencies and publishing houses right after school. I think they thought that the pace for advancement at publishing houses might be frustrating to me, and that my entrepreneurial spirit might be better suited to an agency environment.

It was explained to me that you will do “editorial” work on either side. As an agent, you might spend more of it looking at the ten thousand foot editorial stuff: Does this ending work, does this character work? On the publishing side, it might be more a matter of refinement and on the line level. The first was more attractive. I also learned that on the publishing side, I would be doing editorial plus marketing, but on the agent side I'd be doing editorial plus sales. I didn't know anything about marketing and I knew a lot about sales.

I figured all those smart people couldn’t be wrong and that I should try my hand at agenting.

How did you start?

I applied with no real strategy to a bunch of agencies—though I elected to apply to smaller companies rather than the bigger agencies, thinking that there might be more room to move up more quickly.

I went to work for Nick Ellison at Sanford Greenburger. He said, “This business is not rocket science. I have a feeling that you’ll soon be worth more to me as an agent than as an assistant, and as soon as you and I agree that you understand how a book contract works and the basic rules of the game, you can start building your own list.” That was what I was looking for. I knew from the informational interviews I’d done that it takes two to four years to get promoted even to that first level, whether you’re at a publishing house or at an agency. What I wanted was somebody to say, “I will place no artificial constraints on your ability to advance. It’s entirely up to you.”

How did you develop those skills?

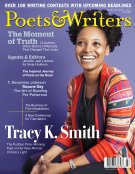

I educated myself as much as I could, reading Publishers Weekly and Poets & Writers Magazine and anything I could find that wrote about the inside perspective on publishing—which houses were which, who the editors were, how people bought books, what they were looking for. I read the slush pile voraciously, and I was very lucky that I knew a bunch of interesting people from different walks of life, many of whom wanted to write books. I took advantage of whatever information and connections I could get access to.

I sold my first book five months after I started, and then I sold another book, and another. Colin Harrison at Scribner bought the first book I ever sold. We had a lovely meeting over drinks, which was my first such meeting in publishing. He called me not too long after that and said that he and his wife, Kathryn, had had dinner with Binky Urban and Ken Auletta; Kathryn is represented by Binky, and Colin is represented here at ICM by my partner Kris Dahl.

Binky had indicated that ICM might be looking to hire a young agent and he put my name on her radar screen. I think I had sold two or three books by then, and not for any significant sum of money.

It didn’t take me long studying the publishing business to know that ICM was where I wanted to be, but I didn’t know how to get here. Colin said, “You’re now on her radar screen. Just keep doing good work and wait for the call.” Not too long after that, I sold a book for an appreciable sum of money and Binky invited me to lunch.

What was that first book you sold to Colin?

Young Men on Fire by Howard Hunt, a novel set in 2001 about a pair of brothers who have gone very different ways in life and are matching their skills against each other during this madcap evening on the town in New York. A lot of the characters worked in big business and really didn’t know what they were doing, but tried to make the most of these crazy opportunities that they had. I recognized that world immediately, intuitively. The book was in the slush pile and I brought it to my boss, Nick. He ultimately said, “It’s not for me, but I’ll support you in your submission if you want this to be your introduction to publishing. Knock yourself out.”

What gave you the idea to send to Colin, who was just then moving from Harper’s magazine to Scribner?

I read an article in Publishers Weekly about his move. I will confess that I hadn’t read a ton of Harper’s at the time, but I looked at the writers he had worked with, and because he is a novelist himself, I also looked at what he wrote and I thought it would be a good match.

Do you regularly do that kind of research?

I do. I’m an information whore. I love information. I read as much as I can, but I don’t remember it off the top of my head as well anymore, so I have to write everything down now. I still consume information about our business and the people in our business, what they like and what they want.

Do you think your approach is different than other agents?

I don’t know why anybody wouldn’t do that, but I think I do have more of an appetite for it than most others.

What was the book that got Binky Urban’s attention?

It was the book that eventually became The Rule of Four, by Ian Caldwell and Dustin Thomason, which at the time was called “The Best and Last.” It was almost two years from the time it was bought to the time it was published, and a lot transpired in that time.

You sold it when you were at Sanford Greenburger, but by the time it came out you were at ICM.

Exactly.

The authors of that novel have an interesting story—weren’t they childhood friends?

They were. They were best friends who were both really interested in writing and storytelling. They were both doing completely different things with their lives but got together at the end of their senior year in college and said, “Why don’t we try to write a novel this summer?” And that’s how it started.

How did you come to be involved?

I went to college with Dustin Thomason and was involved from the first conversations with him and Ian Caldwell. The three of us had a chat at some point about which school the novel should be set in. We decided on Princeton because it was less represented in film and literature and therefore we might have been new things to say.

I knew that they had what it took. They’re both special guys; they’re both incredibly creative and talented and ambitious and diligent and passionate and they were going to figure it out. I went along for the ride, at first in a completely informal capacity. I figured the worst-case scenario was that I’d learn something, and in fact when they first submitted their novel I was still an investment banker.

But it didn’t sell the first time out.

No, it didn't sell originally. Susan Kamil, who eventually bought and published the novel, had seen a lot of potential in it. A lot of people had seen potential in it, and nobody had bought it. But Susan had taken a meeting with them and given them some good perspective and thoughts on how they might make it more commercial. And they did.

When did you get back in touch with them?

We’d been in touch the whole time. I knew their previous agent had left the business and I suggested, “How about me?” They said okay.

What was that first meeting with Binky like?

It was a great lunch. I got to hear her story and I told her a little bit about myself. It turns out we grew up twenty minutes from each other and went to rival high schools. At the end of lunch she said, “You seem great and like you have a great career ahead of you. If I hadn’t thought that you would be a good fit at ICM, I would have still been happy to have met you, and we’d have lunch again in a couple of years. But I do think you’d fit in nicely at ICM. I’d like you to come and meet my partner Esther Newberg.” And then I did.

You arrived as a full agent, but what was it like learning the ropes from them?

Nothing could be better. I’m always hungry for information, and on the first day that I came here I walked into Binky’s office and asked if there was an ICM way of doing things. I don’t think that anybody had asked her that question before. She thought about it for a minute, and what she came up with was, essentially, “Don’t lie.” It’s an easy rule to follow, but I actually think it’s exceptional. There is a lot of presumption—not of lying but of manipulating information. I could not have asked for better teachers and mentors than the two of them. There are certainly no two better agents in the business. But to watch them just be complete straight shooters all the time? It takes any perceived gamesmanship out of the equation.

Comments

eamelino@gmail.com replied on Permalink

Writing to be read...

Ms. Joel hit the nail on the head: the point of writing is to be read. Publishing, in whatever form, and there are many, is a means to that end. I would add that it is the writer's responsibility to find his/her readers. I don't mean that writers must become publicists, but we are wise if we understand that supporting our publicists', publishers' and agents' promotional efforts helps us find our readers. And we poets often must take matters into our own hands through readings, social media, self-publishing, writers collectives and teaching. Nor do I mean that we must pander to popular tastes. As Ms. Joel points out, even the most complex literary work can have a potential readership numbering in the tens of thousands if not millions. She goes on to add that the publishing industry as a business is not great at finding readers. I know that every contemporary literary writer I've read -- from Ben Lerner to Roberto Bolaño to Eleanor Lerman, etc. -- I've learned about from other writers and readers, not through the promotional efforts of their publishers. Also, the independent bookstores play an increasingly important role in connecting writers and readers. Through author reading events, staff recommendations, book tables and shelf positioning, they are providing a much needed service to both readers and authors.

gloriAP replied on Permalink

indie bookstores

So true about the independent bookstores... I am fortunate to have one in my neighborhood and the owners do a lot of promotion of the sort mentioned. I'm not a good "out-loud" reader but the drawing together of writers and community is so encouraging and pleasurable. Every bookstore needs to have a loyal community as well. Rebound Bookstore in San Rafael, CA. Look 'em up! gpotter