In 1994 Joanne Gabbin, an English professor at James Madison University (JMU), organized a conference to celebrate Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks and African American poetics. Hundreds of people came out to hear Brooks and more than thirty writers and scholars, including Amiri Baraka, Toi Derricotte, E. Ethelbert Miller, and Sonia Sanchez, read and discuss poetry. It was a landmark event for the community, “the seeding place of what is happening today in Black poetry,” says poet Lauren K. Alleyne.

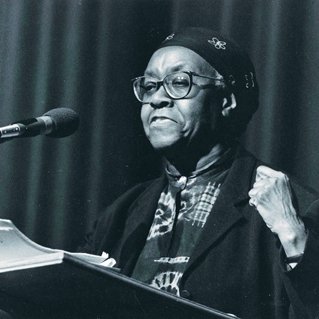

Gwendolyn Brooks at the first Furious Flower Poetry Conference in 1994. (Credit: C. B. Claiborne)

The seed of that conference grew into the Furious Flower Poetry Center, the first academic center in the United States devoted to Black poetry. Located at JMU in Harrisonburg, Virginia, and led by Gabbin and Alleyne, the center is dedicated to teaching, celebrating, and preserving Black poetry as an important part of the legacy of American literature. Furious Flower takes its name from the Brooks poem “The Second Sermon on the Warpland,” which features the lines: “The time / cracks into furious flower. Lifts its face / all unashamed. And sways in wicked grace.”

Since the first conference twenty-five years ago, Furious Flower has served as an example for other organizations and initiatives that have grown to support the community of Black poets—most notably Cave Canem, which hosted its first writing retreat in 1996, and more recently, the Center for African American Poetry and Poetics at the University of Pittsburgh. Furious Flower’s influence extends to the world of literary prizes as well, Gabbin says: “Before the conference there were very few Pulitzers or book awards for Black poetry. Now you can look around and see awards won by Natasha Trethewey, Tracy K. Smith, Gregory Pardlo. I’m really thrilled that Furious Flower had a small part in getting that ball rolling.”

The center will celebrate its twenty-fifth anniversary in Washington, D.C., with a benefit gala on September 27. The following day Furious Flower will host a full schedule of workshops, readings, and discussions at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. The day’s events include the launch of the center’s third print anthology; an interactive discussion on voice in African American poetry, led by Pardlo and Erica Hunt; a reading by poets from Eswatini (formerly Swaziland); and a chance to watch digitized archival footage from the first conference. The celebration will conclude with twenty-five Black poets taking the stage to read their work, a lineup that includes Jericho Brown, Mahogany L. Browne, Toi Derricotte, Camille T. Dungy, Cornelius Eady, Tyehimba Jess, Yusef Komunyakaa, and Danez Smith.

Furious Flower focuses on not only bringing poets together, but also preserving and recording their work. Gabbin had the foresight to record the 1994 conference, which extended the center’s reach by providing a video library of Black poets reading and discussing their work. This educational tool continues to be shared with libraries and students around the world. The center has a large collection of media related to Black poetry, including its own anthologies and a quarterly online journal, The Fight & the Fiddle, which highlights one contemporary poet in each issue.

In addition to its signature conference held every ten years, Furious Flower offers programming to poetry students of all ages: an annual children’s creative camp, a campus poetry reading series, and a summit for college creative writers with renowned poets; last year the organization hosted its first spoken-word academy for high school students. It continues to honor poetry elders with its Legacy Seminars, which bring distinguished Black poets to campus for in-depth explorations of their work to help professors and educators teach the next generation of poets and scholars. Seminars have been held with Lucille Clifton, Sonia Sanchez, Yusef Komunyakaa, and, most recently, Nikki Giovanni, in June.

In thinking about the center’s future, Alleyne says it is important to continue to ask and answer the question, What do Black poets need now? “When Joanne created the first conference, what was needed was to be seen, to be heard, to be recognized and validated,” Alleyne says. “Right now we need scholarly and digital work to make sure that Black poets are also considered in the landscape of American poetry—through digital archiving and preservation, we need to make sure we are in the future as well.”

LaToya Jordan is a writer from Brooklyn, New York. Follow her on Twitter, @latoyadjordan.