When he was chosen by President Obama to serve as the presidential inaugural poet in 2013, Richard Blanco was only the fifth poet in U.S. history to receive the distinction, following Elizabeth Alexander, Miller Williams, Maya Angelou, and Robert Frost. At age forty-five, he was also the youngest, and the first Latinx, immigrant, and openly gay poet to be given the title. By then he was already the author of three award-winning poetry collections: City of a Hundred Fires (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1998), winner of the Agnes Lynch Starrett Poetry Prize; Directions to the Beach of the Dead (University of Arizona Press, 2005), winner of the PEN/Beyond Margins Award; and Looking for the Gulf Motel (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012), winner of the Thom Gunn Award, the Maine Literary Award, and the Paterson Prize. His latest collection, How to Love a Country, published in March by Beacon Press, was inspired in part by his experiences as the inaugural poet. While the poem Blanco wrote for Obama’s second inauguration, ‘One Today,’ celebrated what unites us as Americans, the new book explores the idea of division—of politics, of a nation, of selfhood and identity and home. The new book revisits some of the more personal themes that have infused Blanco’s previous work, such as his experiences as a young gay Cuban American man growing up in the United States, but it also expands its reach to embrace larger cultural issues of immigration, homophobia, racism, gun violence, and the vast and varied forms of injustice that both divide and increasingly seem to define our country. On a broader canvas than ever before, and at a time of stark political division in the United States, Blanco’s new collection questions the very makeup of the American narrative, and ultimately asks what it means to be American.

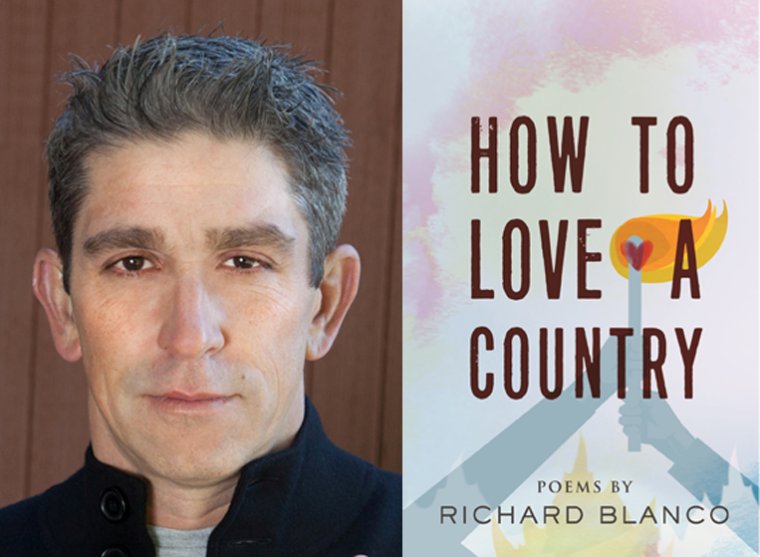

Richard Blanco, author of How to Love a Country. (Credit: Joyce Tenneson)

Richard Blanco was born in Madrid to a family of Cuban exiles and was raised in Miami. He earned a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering and an MFA in creative writing from Florida International University, and has been both a practicing engineer and a poet for much of his adult life. In addition to four full-length collections and several chapbooks, he has published a short book of nonfiction, For All of Us, One Today: An Inaugural Poet’s Journey (Beacon Press, 2013) and a memoir, The Prince of Los Cocuyos: A Miami Childhood (Ecco, 2014), which received a 2015 Maine Literary Award and the 2015 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Memoir. His poems and essays have appeared in numerous publications and anthologies, including Best American Poetry, Great American Prose Poems, the Nation, the New Republic, the Huffington Post, and Condé Nast Traveler, and he has been featured on PBS, CBS Sunday Morning, and NPR’s All Things Considered and Fresh Air. Blanco has been awarded a Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference Fellowship, two Florida Artist Fellowships, and a Woodrow Wilson Visiting Fellowship, and has taught at Georgetown University, American University, the Writer’s Center, Central Connecticut State University, and Wesleyan University. He is currently the education ambassador for the American Academy of Poets and a distinguished visiting professor at Florida International University. He lives in Bethel, Maine.

You’ve said in the past that you consider yourself apolitical, and yet How to Love a Country—which opens with the poem “Declaration of Inter-Dependence”—feels both deeply personal and specifically political. Can you talk about that identification as apolitical as it relates to your work, and how it might have been shaped by your personal experiences and upbringing?

I would first need to acknowledge that the mere act of creating something that questions the world and one’s life in it, that exercises one’s imagination, or that even pens something simply for the sake of beauty, is a kind of politics because it is determined to create awareness of some kind in some context. Art refuses to accept the status quo and that impulse makes it political, whether expressed in a grand and public way, or a more intimate and subtle way. I rejected the former mode because of my experiences growing up in Miami during the 1970s and 1980s, a time when the city was highly politicized by the Cuban exile community. Early on I became painfully aware of polarizing effects of politics and learned that the truth often lies in the grey area. And so, in my first book, City of a Hundred Fires, I made a conscious choice to avoid the politics of polarization and instead focus on my role as an emotional historian; that is, to explore, record, and honor the pain and joys, the losses and triumphs, the sorrows and hopes of all those affected by politics, but without being overtly political. In that regard, I considered myself apolitical, and went on to write two more books in that same vein. Though as I think about it now, even the choice to be apolitical is, in a way, a political choice, right?

It seems as though your inaugural poem, ‘One Today,’ was filled with hope, even as it dealt with the tragic Sandy Hook school shooting. It seems to suggest that, even amidst tragedy, the American Dream is not only alive but also more within reach than ever. How to Love a Country, meanwhile, seems to take a more complex look at a complex place. It feels not only more political, but also more urgent. What inspired that shift?

A lot changed once I was tapped to serve as presidential inaugural poet, which is arguably one of the most political and public moments a poet can experience. Since then I began to more deeply contemplate and explore the civic role poetry can and ought to play in questioning and contributing to the American narrative—the very narrative that I had been left out of as a Lantix, immigrant, and gay man. What’s more, I realized that I had an artistic duty and an emotional right to speak to, for, and about millions like myself from all walks of life who felt as marginalized as I did, given the various sociopolitical issues that historically and presently haunt America. All this unearthing culminated in the new collection, How to Love a Country, which indeed focuses on the intersectionality between the private and public self, the personal and political posture, and the individual and the collective identity of nationhood. The election and presidency of Donald Trump made the book even more urgent. So I guess I could now say that I am a political poet, something I never thought I would call myself outright. However, I still maintain that the truth is found mostly in the grey. As such, I intended the poems in this book to do more than protest the obvious or simply speak to the choir. I wanted the poems to foster a new, unpolarized “third” conversation, to stimulate new dialogue about the nuances and truths we’ve perpetually failed to acknowledge, and to essentially promote compassion and love as radical political acts.

Speaking of acknowledging truths and promoting compassion, one of the most moving poems in your new collection, ‘El Americano in the Mirror,’ looks unflinchingly at what it means to be a child starting to understand and struggle with his sexuality, as well as the violence, ambiguity, and uncertainty associated with belonging to a nonwhite immigrant community. It’s only now that we are even beginning to look at intersectionality and acknowledging the ways in which culture and gender, for example, may intersect with one another. Could you take us briefly through your journey, beginning with that confused early sense of belonging, to the place where you are now—an openly gay poet who can, with incisiveness, honesty, and comfort, explore issues of culture and sexuality?

For years I didn’t come out in my poetry; though I was leading an openly gay life my work never really addressed my sexuality directly. All the while, I felt guilty for not doing so, wondering if I harbored some kind of internalized homophobia that kept me from broaching the subject. At the same time, I also felt that I needed to fully explore issues of my cultural identity before I could explore my identity as a gay man, thinking I had to “resolve” the former before I could move on to the latter. I saw the two as separate matters until my third poetry book, in which I explored how they were indeed related. How my yearning for home in the cultural context as a Cuban American intersected with my gay-child self who yearned for home in the context of a safe space, a haven, a community where someday I hoped to live without fear or shame, and be fully accepted. What’s more, I discovered the more complex story that I wanted to tell, which wasn’t solely about my culture, nor solely about my sexuality, but about the intersection of these—my cultural sexuality, as I like to put it—and how they inform and affect each other. I had mistakenly siloed these two identities, when actually, the way they merge and collide—along with many other identities—is what gives rise to our most unique and compelling work.

What about the intersection, if I may call it that, between languages in your work? In some poems you explore how Spanish and English “inform and affect each other”: “Like memory, at times I wish I could erase / the music of my name in Spanish, at times / I cherish it, and despise my other syllables….” How does being bilingual enrich your writing life and linguistic sensibility?

I didn’t have a “first” language; as far back as I can recall, I’ve always known Spanish and English. By the time I was three or four years old, I was translating words and phrases for my parents, helping them navigate their new lives in the United States. Those early childhood experiences instilled in me a hyper-awareness of the importance, mystery, and power of language. That’s probably why I was eventually drawn to writing poetry. The linguistic and cultural contrast of living bilingually shaped my sense of language, not merely as a strict mode of communication, but as a fluid way of thinking, feeling, and being. Sometimes I’m the Spanish, Ricardo; sometimes the English, Richard; but mostly I exist as a blend of both, which is reflected in my poetry in several ways. My mentor, Campbell McGrath, often described my work as lush, rich, and textured, which I’ve come to see as a kind of emotional translation of the very lushness, richness, and texture of how I feel and live in Spanish, but expressed in English. However, at times I refuse to translate certain words—like names of foods and terms of endearment—because there are no equivalents in English. These Spanish “word bites” add another dimension of sound to the poem. I’m also fascinated by the pleasure of rhyming sounds across languages—like soul and sol (sun)—and how such pairings evoke meaning in a fresh way, not otherwise possible in a monolingual poem. Then there are the poems that I like to cocreate in both languages simultaneously. I’ll begin with a line in Spanish, translate it into English and play with the syntax and images; then reverse translate it the back into Spanish—toy with the line again, then translate it a second time into English—and so on and so forth—until I’m satisfied with the line in both languages, and move on to the next one. Typographically, I’ll lay out the finished poem as a single, inter-mingled text—not as a poem and its translation—to reflect how the bilingual, bicultural mind code-switches back and forth between languages. Through the writing of these kinds of poems l dive deeper into each language. I’m able to more closely examine the linguistic intricacies and English by contrasting it to Spanish, and vice versa.

Deep-diving is part of revision, I assume. How do you revise a single poem, and how do you envision a book-length collection?

Revise, revise, revise—a poem is never done. That’s the mantra ingrained in most of us. While, of course, I do believe revision is key, I also believe there are other notions to consider. I’ve found that revision for the sole sake of revision is usually a waste of time. I don’t revise unless I am inspired to revise with some direction. And I usually find that direction, not by staring at the computer screen for two hours, but by getting back into my body, into the world of the senses. Usually a take a walk, or do some breathing exercises, or simply pause and look out the window to notice and wonder. As for arranging poems in a collection, the most successful strategy I’ve found—as a starting point—is to lay out the poems chronologically in the order they were written. When I do that, I begin to notice what my subconscious mind had been trying to work through, and how. Usually, that reveals the major movements of the book and emotional arc it will take.

Emotional as your poetry is, it’s often funny, too—as in poems like “Let’s Remake America Great.” What role does humor play in your writing, and how can it help or shape a poem?

I incorporate humor or irony in some of my poems, not merely for the sake of getting a laugh, but to reflect the tragicomedia—the “tragicomedic” character and idiosyncrasies of my Cuban culture—of living in Cuba. We can be so dramatic that we become melodramatic and comical. One minute we’re crying, and the next we are laughing. Or laughing and crying at the same time! However, whether I’m writing about my culture or not, humor is part of my sense of life and language, and that’s why it appears in my poetry. Perhaps analogous to catching more flies with honey than vinegar, I use humor to catch readers and invite them into the poem in an unassuming, unpretentious way that reveals and imparts certain truths more subtly, and yet more powerfully. But humor is tricky. When it’s overused or misused, I find a poem can begin to sound like a stand-up comic routine. The “funny” poem at some point has to turn to reveal a certain gravitas that pushes back against the humor and confess what is emotionally at stake. It’s sort of a limitation of poetry as a genre; it can hold only a so much humor, in contrast to prose that can hold a whole lot more. In part, that’s why I wrote my first memoir—to squeeze in all that extra humor and backstory that never found a place into my poems.

In addition to writing memoir and poetry, you’ve performed poems for organizations such as Freedom to Marry, the Tech Awards, and the Fragrance Awards. You wrote and performed your long poem “Boston Strong,” and released it a chapbook, the proceeds of which went to survivors of the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. You also wrote and read “Matters of the Sea/Cosas del mar” to commemorate the historic reopening of the United States Embassy in Cuba. What are your thoughts on performing poetry?

I had always listened to the rhythms and cadences of language as I “heard” them in my mind and transferred them onto the page. But, to be honest, I didn’t know how to speak my poems; or rather, I wasn’t cognizant of the difference between the page and the stage. Then one day at a reading—I forget where; it was about eight years ago—I remember feeling bored as I read my own poem aloud, and I thought, Wow, if I’m bored, I can only imagine how bored the audience must be! That was the turning point, when I realized that the performance or recitation of a poem is part of the craft of poetry—part of its very DNA dating back to its birth as music and oral tradition. I now read my poems out loud as I work on them, paying close attention to how they echo in my ears and breath in my body, and then I revise based on those sensations. That process also serves as a kind of rehearsal through which I teach myself how to preform the finished poem; or rather, the poem teaches me how it wants to be spoken. I think of the process in musical terms—I am the lyricist, the musician, and the singer all at once. In graduate school, we never discussed the performative component of poetry—we’d just mumble our poems sitting down at our desks. And I’m not sure that’s changed all that much. I think the craft of performance should to be part of our education. We’ve all probably attended a reading where the poet rambles through every poem—whether about roadkill or roses—with the same exact cadences and detached tone, disembodied from the poem as if reading someone else’s work, not their own. I feel cheated when that happens; it turns people off and gives poetry a bad name. The way I see it, if people make the effort to come to one of my readings, I owe them a performance that adds to their understanding of the work—something they wouldn’t otherwise get from simply reading the work on their own. Thinking in musical terms again, a poetry reading should be like going to a musical concert, which is intended to offer audiences a more profound and multisensory experience beyond sitting at home listening to a recording.

Let me be clear: I don’t mean to imply that all poets need to be performance poets—that’s another thing altogether. But I do think it’s important for poets to perform their poems, not just read them. And by “perform” I don’t mean over-acting or over-the-top hijinks; rather, simply embodying the poems. However, I would also point out that it’s not fair to judge a poem solely by its performance: a good performance is no excuse for a poorly written poem, and conversely, a poor performance of a great poem doesn’t make the poem any lesser. The ideal is a great performance of a great poem.

Finally, given the political rhetoric regarding faith in our nation today, may I ask about religion and its influence on your work?

I was raised Roman Catholic but have been pretty much a secular being for most of my life. I’ve found it very difficult to follow any kind of formal theology or religious practice. But I do think of myself as a “cultural” Catholic, meaning that I do retain some of the values and a sense of faith and community that my Catholic upbringing instilled in me. I haven’t entirely thrown out the baby Jesus with the bathwater. I don’t consider myself an atheist or agnostic, exactly. Poetry has become my religion, I suppose. When I sit down to write, I light a candle and call on the spirits of my family ancestors, my literary ancestors, and my inner child to guide me. Poetry has become a kind prayer and meditation that lets me commune with the divine universe and connect to my higher self. The act of creating is an act of faith in one’s self and in the mystery of life itself.

Padma Venkatraman is an oceanographer and the author of four critically acclaimed and award-winning novels for young adults, including The Bridge Home and A Time to Dance, both published in the United States by Nancy Paulsen Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House. She lives in Rhode Island. Visit her at www.padmavenkatraman.com.