Leah Nieboer

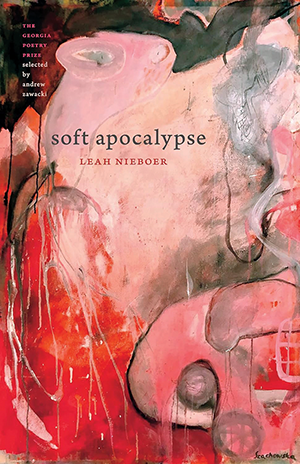

SOFT APOCALYPSE

University of Georgia Press

(Georgia Poetry Prize)

and summer was a slow idea barely

coming around sleepless someone

had called an ambulance

causing a sorrow to appear

on the pavement

—from “THIS WAS AFTER MIDNIGHT AT

THE CORNER STORE”

How it began: I’m a process-based poet, so this book began the way most projects begin for me: with an irritation at the ear, an ambulatory desire, a set of emerging questions, a line or two, and a text—this time Clarice Lispector’s The Passion According to G.H. (New Directions, 2012)—rattling around in my head. At the same time I was leaning into the latter half of 2020, in the high desert, the days stripped back, oversaturated, and full of fear, the news utterly insane, our shared precarity seeming only to increase, and the losses, too, increasing. I started writing through my own flare-up of chronic conditions as the public ones amped up, and I listened, both to the official orders, violations, isolations, and dire projections of that time, and to the friends who were dreaming of and demanding a different world.

“I was seeking an expanse,” Lispector writes in G.H. I was looking for what might exist “between the number one and the number two,” between “two notes of music,” “two facts,” or “two grains of sand”—those mystical-real calculations of matter that release previously unthinkable measures, arrangements, and relations from within the seemingly rigid confines of the present. That jived with what I was reading, via Lauren Berlant, Derek Jarman, and José Esteban Muñoz, on collective life, dreams, queer futurity, and worlds within worlds. I was thinking about the future, not as belonging to a temporal scale, but as something belonging to space and its rearrangements, something an erotic trace of the past or present can release, something we can perform through our rhythms of relationship.

I asked, “How will we live together?” and Muñoz insisted, “[W]e must dream and enact new and better pleasures, other ways of being in the world, and ultimately new worlds.” I attuned to the places where our boundaries or proscribed means of relationship dissolved. Paid attention to exchanges with the cashier at the corner store, beyond the cash, but that too. I watched every place hands touched, brushed by, or passed through each other. Listened to the human and nonhuman rhythms in my neighborhood, especially at night. I had increasingly vivid dreams and wrote them down. I watched the sleepers in the subway car in the film Sans Soleil (1983) with their dreams bumping together, a couple of nurses and a doctor working wires on and around me one long night in the ER, and figures in white linen circling Derek Jarman, dreaming on a bed in the shallows in The Garden (1990). I looked for all the unruled complexity in our minor moments of contact, those that escape measure but might offer a way of performing the future here.

Inspiration: The book is inflected with the dreamers, futurists, mystics, performers, and improvisers mentioned above, as well as Simone Weil, James Baldwin, Fred Moten and Stefano Harney, Gertrude Stein, Marina Abramović, Dionne Brand, André Lepecki, Hillary Gravendyk, Salomé Voegelin, John Coltrane, my friends, and a number of strangers. My grandmothers. Rilke’s angels, gods, and strange beloveds inform those in SOFT APOCALYPSE, though I saw those figures differently—for example, riding out of a dizzying heat on the back of a chrome motorcycle. My next-door neighbors who fought, or made up, all night long. A woman I met years ago in line at the pharmacy, who really did read the silent pain all over my face and slipped me a loose Vicodin, bless her. The days I spent at the public pool in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where I was in touch with others at a distance via the water, found fluid possibility there, and managed a little healing. And the nonhuman clatter, too—radio static, the slice of a skateboard, a bird cutting a vector through the air—that animate grammar that makes us up, entangles us with the whole sentient world, and speaks us around. I’m in love with all of it.

Influences: Emily Dickinson was one of the first poets I read and had access to (you can find her in a public library) and the longer I read her work, the stranger, riskier, and more inexhaustible I find it. I love her ear, her incredible economy, the atomic energy of her lines, and the dash, whose rigorously precise employment Heather McHugh calls “that undecidability, which is not an indecision.” I feel marked by that dash, in my being.

Soon after I began my MFA, my aunt died young, inexplicably, and, a few months later, a new onset of chronic conditions slowly then utterly irrupted my patterns of thought, motion, and articulation. My relationship to language changed. I felt an increasing affinity with writers and artists who worked with dissonance, rupture, and silence as necessary elements of making, who needed experimental forms to get by, or who simply played at those edges where logic drops into an astonished knowing and the word gives way to what escapes measure. A not-exhaustive list includes Elaine Scarry, Fred Moten, Susan Howe, Nathaniel Mackey, Andrew Zawacki, Gustaf Sobin, Gertrude Stein, Lyn Hejinian, Samuel Beckett, Ruth Asawa, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Roland Barthes, Jorge Luis Borges, C.D. Wright, Hélène Cixous, Bhanu Kapil, Rosmarie Waldrop, Clarice Lispector, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, and Paul Celan. This convocation of others helped me find a possible path in poetry, as did the teachers who shared many of these works with me: Brooks Haxton, Heather McHugh, Alan Shapiro, Dana Levin, and Sally Keith.

I came to my PhD program with these others in mind and the word “permission.” While I’ve (nearly) done the required literary work of the PhD and found real comrades on and off the page, my creative work has only gotten wilder and my scholarship more interdisciplinary. I’ll always be in poetry, but I’m leaning further into gesture, performance, sound studies, and embodied knowledges. As the work of the PhD is winding down, I’m making my relationship with listening more...official? I’m working toward a certification through the Center for Deep Listening at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, which focuses on an ethics, pedagogy, and practice developed by Pauline Oliveros, IONE, and Heloise Gold to expand our perception of what is audible, knowable, and sentient through sound improvisation, somatic movement, and dreamwork. This practice, daily and individually, has extended the capacity of my poetic ear, supported my embodiment, and given me a resonant through line for my ongoing questions; in community, it consistently offers possible gestures, economies, and ways of being together in diverse circles that are beautiful and sustaining.

Writer’s block remedy: Most of my writing comes out of impasse: I’m interested precisely in the impasses of the tangible and intangible architectures we inhabit. That’s the frustrating, dissonant place I press my ear to, listening for emergent forms, alternate time signatures, unexpected kinships, or just the aesthetic excess we make rubbing up against each other that somehow escapes the measure of the production machine. All that activity might fail to add up to something, but it might also generate openings.

That’s poetics, but on a practical note, living with chronic illness means contending with limits, arrhythmias, bills, pharmacies, and insurance companies, and what gets lost while you deal with all of it, and how you invent ways of being here when it seems impossible to be here. I let myself be. I keep my ears open and keep paying attention, and I let what I hear circulate through me on its own time. Pushing through burnout is antithetical to the above, and, anyway, it lands me in the hospital. My hope is that, collectively, we can dismantle the disabling, discriminatory labor standards that the academic, publishing, and creative worlds consciously and unconsciously perpetuate. Every body deserves rest.

Advice: Trust yourself and your timing. I imagine anybody reading this and trying to publish their first book might feel like, “Easy for you to say!” but I mean it, and I practice this without ceasing. Don’t let the market or social media make you frantic or alter your measures of yourself or your work. I got a lot of rejections; none of the poems in SOFT APOCALYPSE were accepted for publication until after the book won the Georgia Poetry Prize, and even then, only a few. I’m okay with that. I take care of my materials on and off the page, submerge myself in water whenever possible, try to shush my ego, and keep the work wild and moving. In the meantime, it also helps to celebrate the wins of people you like and admire. Poetry isn’t a zero-sum game—I’m in it because it offers a more imaginative calculus. And I’m a big believer in the way cultivating an abundant mindset leads to more capacious, generous, and creative living and being.

Finding time to write: I keep the ear open and the hand running. It happens in the margins of making life happen, so I’ll scribble a few lines in the morning before work, or jot down what came up in my dreams, record external sounds that catch my ear while I’m walking between destinations, make notes while I’m waiting in line at the pharmacy. Every few weeks I can usually block off a couple of hours on a weekend to sift through what I’ve accumulated and see what I can coax out of what’s there.

Putting the book together: I listen to full albums on repeat for compositional intelligence—in 2020-21 it was an eclectic mix of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme and Blue World, Bach’s Cello Suites, Moses Sumney’s græ, a lot of Mitski, a little Jonny Greenwood, Metallica, Brittany Howard, Sons of Kemet, Cat Power, and others I don’t remember. I study patterns and transitions across genres and media, but especially in films (Yasujirō Ozu, Chris Marker, Apichatpong Weerasethakul).

I printed off the poems I had, left them on my floor for about a week, and looked at them late at night or first thing after I woke up. I cut poems that seemed to be doing the same work as other poems with no real revelations. I cut anything that stalled the book. As I was tinkering with the final, long poem, I realized the book needed to begin and end in the dissolve of night, where it could stay open in the neon lights, and keep performing its gestures, possibilities, and questions, while keeping its secrets and strangenesses too.

What’s next: I’m deepening my listening practice. I’m wrestling with the medical-industrial complex. I’m celebrating all of my two young nephews’ wobbly steps and little wins, which are big to me. I’m thinking about precarity as a site of emergence and a central condition of our being here, and I’m trying to locate my ear at the edge of sound and sense, where what escapes measure is nonetheless sentient, speaking, and emergent.

From those attentions, I’m working out a second collection of poetry that feels truer to chronically ill bodies, both human and nonhuman, in an era of rapid planetary change, global pandemics, persistent inequities, and ongoing capitalist devastation. Rather than focusing on narratives of healing or restoration, my book asks how we live together now, with/in our losses, by desiring, taking care of, and taking cues from our most precarious bodies. I’m also finishing my dissertation, which is similarly attuned; part of it is a speculative novel, set in a fascist, surveillance state, that, overall, explores queer, disabled, and multispecies futures through its protagonist, a kind of reluctant agent of extrasensory perception.

Age: 36.

Residence: Denver.

Job: I’m currently a PhD Candidate in English and literary arts at the University of Denver (and on the job market), so I do a mix of teaching, curriculum design, and other totally nonliterary jobs to support that project.

Time spent writing the book: About sixteen months. I wrote the early poems on the roof outside my window, at night, in the summer of 2020, in Denver, and finished it in Albuquerque, New Mexico (where I wrote the majority of this book), in November 2021.

Time spent finding a home for it: I sent out some chapbooks (all rejected) in the spring and summer of 2021 but only sent out the full manuscript when I knew it was finished that fall. I hustled to get it there; I saw Andrew Zawacki was reading for the Georgia Poetry Prize, knew I loved his work, and hoped he’d be a good reader for mine. I sent it to very few places after that, as I only had so much cash for submission fees, kept on with the PhD and rent-paying work, then I received the unbelievable news in January 2022. I feel very lucky.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: I was struck by the ease and precision of Tommy Archuleta’s Susto (Center for Literary Publishing), its lyrics and rituals, its deft means of keeping what’s soft and brutal, or simply irresolvable, together in mind. It’s ensouling. While rigorously particular to Archuleta’s memory, beloveds, cultural wealth, and the landscape of northern New Mexico, Susto seems to offer instructions and postures for survival any reader would be wise to heed in our time (and I will). I read Olivia Muenz’s I Feel Fine (Switchback Books) during my own clinically saturated summer, its punctuated prose aptly overlapping personal and impersonal intimacies, forced performances, disclosures, monetary scarcity, bodily excess, bare needs, and digressive desires to get at the insoluble plurality of disabled embodiment. The plain hard work of being in the body is checked by necessary levity so that lines like “Let’s blow this popsicle stand” land with a kind of glittering gravity. I’ve just gotten my copy of Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola’s the Telaraña Circuit (Tender Buttons Press) and look forward to being with its forms of tracing sounds, patterns, and bare pulses via multiple modes of listening across material and immaterial archives.

2023 was also an abundant year for debut releases among my extended cohort of writers from the Warren Wilson MFA program, which made my own a thousand times sweeter: Sarah Audsley’s Landlock X (Texas Review Press), Jennifer Funk’s Fantasy of Loving the Fantasy (Bull City Press), Sebastian Merrill’s GHOST :: SEEDS (Texas Review Press), Margaret Ray’s Good Grief, the Ground (BOA Editions), and Cynthia J. Sylvester’s The Half-White Album (University of New Mexico Press). We’re all wildly different writers, but their shared, tenacious dedication to their craft ensures I’ve got to keep elevating my game too.

SOFT APOCALYPSE by Leah Nieboer

![]()

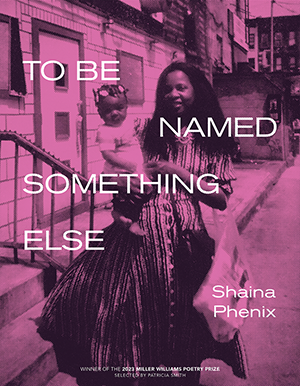

Shaina Phenix

To Be Named Something Else

University of Arkansas Press

(Miller Williams Poetry Prize)

lending your blood

to four babies

with mountain mouths

stitched in a legion

of things misplaced and found.

—from “Lucille”

How it began: I don’t think I set out to write a book at first. It was a faraway maybe, a one day. I was, however, writing with commitments in mind. I was committed to poems as official documents of histories, experiences, and the voices of Black women/femmes, folks of my blood, other kinds of kin, and not kin. I would write our names next to living things like trees, dirt, natural water, hair growing from our scalps, the sun, and God, so that we may live. I would transcribe our secrets, inside jokes, rituals, recipes, songs, stoop talks, and testimonies so they may speak for us in the event that we did not get the chance to speak for ourselves. I would write to interact with a set of pasts for fellowship and congregation between a Black-was and a Black-is. For a while I noticed that every poem I was writing was informed by, in honor of, and in conversation with a before—lineages, myths, and inheritances. Every poem had connective tissue between itself and something, someone, or someplace that existed before it. Varied histories of Blackness, Blackhood, and Black survival were the marrow of the poems and of my work in general.

Then, with the assistance of my MFA experience and having to cull a collection of work that would represent what I had done during my three years in the program, there were threads I had to name. Some of the work from my MFA thesis became anchor poems for this book. I built my understandings of what I wanted the book to have in it and what I wanted it to be doing from there. There were poems that were speaking to one another, or had people showing up over and over again, ghosts I couldn’t shake, places—my childhood homes, the church—my body, voices, and all other kinds of Black living and not-living selves; I think I knew then that there was a larger work coming together.

Inspiration: My families: chosen, blood, built, and fought for. The “Little Black so & so’s” that I’ve seen born, grow, find joy, and live. My students. Harlem, in all its selves and iterations. My mother, her mother, her mother’s mother, and so on. My mentors, teachers, guides, spirits. My ancestors. God. The nineties. Black everything: music, culture(s), people, food, clothes, living, survival, and and and. Everyone living in this country that wants them dead.

Influences: The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton 1965-2010 (BOA Editions, 2012) opened something inside me. Lucille Clifton has helped me to recognize the poem as a form of preservation, a way to pass down the stories that might otherwise become lost. Through interactions with her work, I committed to poems exploring Black girlhoods and womanhoods (my own, passed down, and observed) and telling stories of my blood, my lineage. Clifton wrote God, the women from which she came, and the women who came from her, in ways that all felt equally holy and indispensable. In Clifton I realized that poetry could do the work of keeping histories, especially the ones that weren’t photographed and could not be discerned from birth certificates or social security cards. In Clifton’s work I got permission to write the way my grandmother says, “Lord have mercy, Jesus, and...” never knowing where she’ll go with that statement until the “and” has passed; to write Harlem, the thick and choppy accents, and how I yelled across the street to my friends, “Was poppin’” and “What’s goodie,” sashaying down 135th street to a corner boy chorus of “Ayo ma! Excuse me miss, can I talk to you”; to imagine Black heavens where my great grandmother, Shug Avery, and Lucille Bogan smoke a cigarette together.

Sometimes I wonder if I would have found Lucille Clifton had I never met Aracelis Girmay. I’d like to give the universe some credit, to say that I would have found Lucille Clifton’s work, or it would have found me in some sort of way, but Aracelis handed me The Collected Poems of Lucille Clifton 1965-2010 at one of the worst moments in my life. And while the poems didn’t cure the thing that was eating at me, they did hold my hand, hard. In so many more ways than this, Aracelis—her work, her teaching, her mentorship—made me feel possible, as both a human and a poet. Early in my relationship with writing, especially in academia, she encouraged me to experiment, to say what I meant even if everyone couldn’t understand it at first. She taught me about audience, about listening, about allowing the poem space to be what it needs to be and not what I mean for it to be. She taught me to notice how writable the things I carried were, even when they felt unworthy of writing to me.

There are so many others I want to name: Lil’ Kim, Ntozake Shange, Audre Lorde, Reverend Dr. Alfloyd Alston, Toni Morrison, Foxy Brown, Bhanu Kapil, Ilya Kaminsky, John Murillo, and and and.

Writer’s block remedy: I don’t know if I call what happens “writer’s block”, as I believe so many things are writing (or maybe I tell myself that so I don’t feel bad). When I am not writing with pen to paper, I am considering the other activities that I’m doing and how they might help me return to paper when I’m ready. When I’m at an impasse, I consider what my questions are, what I’m missing, what I might be hiding from, who I might be hiding from. I return to something that already exists and I try to see it in a new way. I’m revising, rethinking, reimagining, or all three. I’m reading. I’m taking long walks. I’m writing down all the sounds I notice, all the colors, all the things that scare me, all the things that make me smile, knowing that I can store them for later use. This active noticing or observing also feeds what I write when I sit down to finally do it. In this way, I’m always writing and remembering that my literary practice looks different on me at different times.

Advice: (1) Talk to people who have published books—I wish I had done more of this myself. Ask them about their experiences, publishing companies, the process of putting the manuscript together and releasing it. (2) Write until you notice you are returning to something that’s already been accounted for. When you’ve made a circle in some way, then you have a draft. (3) Get readers! Both writers and nonwriters. Read to your loved ones and see how they respond. Make note of it. Come up with questions. What do you want to know about your work? What do you want to know about how people are reading your work? What’s missing? What haven’t you seen, heard, or said yet? (4) At some point, let it go. I don’t know how to say how, but you must at some point.

Finding time to write: Sometimes I don’t, but when I do it mostly feels like I’m stealing or making the time to write. Sometimes I have to pull time out of thin air: When I give my students writing prompts in upper-level creative writing classes, I write alongside them. When I take long road trips, I voice record snippets of maybe-poems. When I have fifteen or twenty minutes before a class, I return to a half-done poem or a poem in need of revision, and I do something with it before I head out. Other times I go off-grid for a few days to write until I can’t anymore, to wring myself out.

Putting the book together: I was staying with a brand-new lover at the time that I had begun organizing the manuscript. She had a long, empty wall in her house, catty-corner to her office desk. I don’t remember if I asked for permission or if I just started taping poems on the wall, but every day that summer I’d spend a few hours at that wall saying, “This poem belongs with this one…I need a poem about love right here, another kind of grief poem here…. My queerness feels quiet, how can I make it louder,” those kinds of things. I thought not of what poems belong together by theme or subject matter but what poems could be in conversation with one another. The sections and their titles came after I had grouped the poems in their respective conversations.

What’s next: Everything? I am writing in so many directions right now, between two, maybe three projects, and usually I would try to narrow down what feels most important at the time, but I’m letting my brain do what it wants. What I feel most excited by in this moment is what I imagine will be a second book of poems that takes place in an imagined subaquatic world in which Black people—murdered, passed on, or imagined—live among one another at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean and lead the lives they didn’t previously get a chance to. I’m also working in creative nonfiction on what might end up being a collection of essays fixated on shame. So far the essays center both personal and collective experiences of girlhood: how we build, unbuild, and exist in gendered and racialized identities, and what we do with these buildings and the cities in which we house them.

Age: 29.

Residence: Burlington, North Carolina.

Job: I’m an assistant professor of English at Elon University.

Time spent writing the book: The poems in the book span about five to six years’ worth of writing. The oldest pieces are snippets of a longer choreopoem that first came to be during my undergraduate years (2015 to 2016), and while that was a different kind of writing for me, as it mixed interview responses that I didn’t want to change too much with poetry, it felt like the mother of this collection.

Time spent finding a home for it: I knew I wanted to be published through a book prize of some sort, because that was what felt most familiar to me. So once I decided the manuscript was finished(ish), I started checking deadlines for first book prizes that I knew of and did research on ones I did not. I ended up sending to two prizes. They were due around the same time, so I submitted to them at once and waited.

Recommendations for recent debut poetry collections: I’m Always So Serious by Karisma Price (Sarabande Books), Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley (Knopf), Remedies for Disappearing by Alexa Patrick (Haymarket Books), and Freedom House by KB Brookins (Deep Vellum).

To Be Named Something Else by Shaina Phenix

India Lena González is a multidisciplinary artist and the features editor of Poets & Writers Magazine. Her debut poetry collection, fox woman get out!, was published by BOA Editions in 2023.