Last June, Ricardo Alberto Maldonado became the first Latinx president and executive director of the Academy of American Poets. Founded in 1934 “to support American poets at all stages of their careers, and to foster the appreciation of contemporary poetry,” the Academy fulfills this mission through programs such as National Poetry Month, the Poem-a-Day e-mail newsletter, funding for poets laureate, and poets.org, which offers free poetry resources. It also sponsors national book and literary prizes. Maldonado took the reins at the Academy after a career in education and arts administration, last serving as director of the Unterberg Poetry Center at 92NY in New York City. Maldonado recently reflected on his start at the Academy and his vision for the organization’s future.

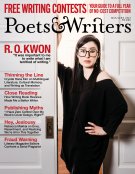

Ricardo Alberto Maldonado, the president and executive director of the Academy of American Poets. (Credit: Nancy Crampton)

What has surprised you so far about your job?

Everything. I feel very lucky and humbled to be at one of the many centers of conversation on poetry and its impact. On any given day I’m in conversation with twenty to thirty poets from all sorts of backgrounds, whether they are funded by our poets laureate program, or a Poem-a-Day editor, or someone who is featured [in Poem-a-Day]. I’ve also been having engaging and insightful conversations with translators. Part of the beauty of the Academy is that it was founded as a member-supported organization, and members write to me often about the poems they read, whether they like them or not, about programs they’d like to see, [and] poets they’d like to see [in Poem-a-Day]. The chancellors [of the Academy’s governing board of chancellors] also write to me once in a while with ideas. It’s pretty humbling. Everyone is invested in the promise of the Academy.

The letters that have moved me are letters from older writers who never knew that writing was possible, and they wrote their first poem and wanted me to see it. I expected that a position like this means that one is constantly visible. I’m not surprised that I get these letters and e-mails frequently. I just wish I had five Ricardos to answer them. It is one thing to believe that the work of poetry is making a difference and another to see it. People would approach our table [at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference this year] and say, “My poem was published in Poem-a-Day, and then my book was published.” It was a reminder that we have more of a presence than we know.

The Academy recently got $5.7 million from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Tell me how the funding will support the Academy.

Through the grants we are able to increase the reach and impact of the poets laureate activities. These grants allow poets to have some income, to fund their activities and also to fund potential collaborators. We’ve provided around $370,000 in matching grants to forty-eight nonprofit organizations that are working with poets laureate. We are seeing poets laureate popping up all over the United States. More than forty new laureateships have been established since 2021. In many cases this is a public’s first contact with a living poet. The look of a young student when they realize that they themselves can be a poet and that poetry is being written and rewritten, that’s unmeasurable.

[The grants will also support] the Poetry Coalition, a group of close to thirty nonprofit organizations, and that has [created] this feeling that [the poetry community is] no longer insular. Skill-sharing is important, and conversations about what’s going on and how we can do better are central to what we do. Partly due to the great work of [previous executive director] Jen Benka, the Academy has become a major supporter of other organizations that are doing work and making the case for diversity and inclusion. We are building a bench of younger BIPOC administrators. We are also offering professional development opportunities for members of the coalition. We’ll be doing a session on archiving and a session on fund-raising. You need to know about development and about archives so you know how to steward your [organization’s] history and look toward the future.

You are a poet who writes in both Spanish and English, and you’ve spoken elsewhere about bringing more linguistic diversity, specifically Spanish, to

poets.org. Why is that important?

Since I started thinking about becoming a poet, I became ravenous in my reading. The notion of a border was nonexistent. Louis Zukofsky said, “Talk is a form of love / Let us talk.” That is what I feel informs the work of translation. It is a fact that the U.S. is home to communities that speak languages that are not English. It is important to include work that is reflective of all the communities we serve. I was just reading an interview with Joy Harjo, who is an Academy chancellor, and she talks about being in conversation with Whitman and Ginsberg, so that also means Lorca and Neruda, and some of those works come to us through the agency of a translator. There are many languages and many poets from many countries I’d like to have on poets.org.

Does the word American in the organization’s name create any boundaries on what you publish?

As an administrator your work is to constantly be expanding the horizons of your readers. Even with our name, we’ve been able to feature work that reflects collaboration between more than one language, and we also offer prizes in translation. We ask ourselves as member citizens: What is this country? What does America mean? I just feel like there is an implicit negotiation under that title [Academy of American Poets] that is generative for poets and readers. I do not want [the word American] to be a boundary; I want it to be something we can question and challenge and expand.

How does a landscape in which universities are withdrawing support from literary magazines and even from literature departments change the role of the Academy of American Poets?

We are lucky enough to have an organizing principle that allows us to be investing in poetry. It is distressing to hear that universities are not providing support for literary magazines or literature departments. Our citizenship, our sense of the world, is amplified by poetry. My lived experience is that poetry can be something like secular faith in what we have to offer one another. I’d like this to be corroborated by institutions and community centers all over the U.S. and all over the world. The world needs more poets because poets evaluate how language matters and why it matters and how the world that we build with language matters. We can do that work through the Academy. Poem-a-Day is a great example. But I want to see a plurality of venues. I want to hear a poem every day on NPR, to see a poem each day on the bus—which I do, because I live in New York City—to see a poem when I go to open up my container of oat milk.

Do you have a vision for reaching more venues?

I used to be a teacher, and when I was at other arts organizations, I was part of a team responsible for educational curriculum for high school students and adult learners. When I came here I wanted to bring my experiences with education to the forefront. [In the 1960s], Robert Frost wrote to our founder, Marie Bullock, and said that the best way to make a case for poetry is to bring poets into the schools. We will be working on curriculum development with teachers and education specialists to make sure what we provide to schools and to students is exactly what they need. Even at AWP teachers [said] to me, “I use Poem-a-Day, but sometimes I feel like I don’t know how to teach a poem.” Well, I can change that. I came to the Academy with that intention—to be of service to teachers, therefore students, therefore readers, therefore possible poets, therefore their friends, therefore their families. We are going to be doing literary seminars for adult learners as well at the Academy.

During the pandemic we gained an understanding that people were looking to connect. [I learned that] what I thought could only happen in person could happen online across the world—people talking deeply about poetry. We will have poets, critics, and scholars delivering a series of lectures on books through online literary seminars. The first one will be Carl Phillips on Gwendolyn Brooks’s work. We have classes lined up on Gilgamesh, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and we are working on a class on sonnets.

How has working in arts administration influenced your work as a poet?

Secretly, or not so secretly, one of the working titles of my manuscript was “Not for Profit Administration.” I learned that the administration of art is an art unto itself. I was creatively engaging with what I had to do because it was really having an effect on people’s lives. It taught me to be a reader—of a budget, of e-mails. Most of the work I do is community work, and I have learned more as an administrator than I did in my MFA. I learned about poetry in community, and that made me think deeply about communities when I sat down to write poems. I also have the understanding that I have more to learn. The work of administration comes from identifying those lacunae.

I have read the story about your first coming to poetry as a teen when a teacher gave you a copy of “To an Athlete Dying Young” after your father’s death from cancer. What would you say now to that teenager about the role poetry would come to play in his life?

It was my father’s death that compelled me to want to study toward being a doctor. When I went to college, I wanted to be pre-med. I also wanted to study literature. I knew of William Carlos Williams and knew he was a doctor. I was assigned an adviser, the great poet Deborah Digges, may she rest in peace. I think the universe was sending me a message. I became an English major and finished premed. It was very difficult, but when I was studying organic chemistry and literature, [I thought] aren’t they philosophically dealing with the same things?

I never thought that I would end up at a place like the Academy of American Poets. I realize how lucky I have been for the past twenty years to be in contact with poets as a poet, as someone who can try to make the lives of poets easier. It’s beyond my wildest dreams, and I just hope that somewhere in the world there’s a young poet who never knew that this was a possibility, [who will see me and say], “Oh, wait, I might want to do that.”

Emily Pérez is the author of What Flies Want (University of Iowa Press, 2022), winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, and coeditor of The Long Devotion: Poets Writing Motherhood (University of Georgia Press, 2022).