When I glance back over the notes from my recent interview with expatriate fiction writer Roy Kesey in Beijing, I notice the things I’ve written in a section devoted to his early years in particular: Parents devout Christians. Father college administrator who taught him to play the stock market when he was “ten or so.” Roy deferred paying tuition to Georgetown to “work the penny stocks” and lost it during the Black Monday crash of 1987. Had to leave Georgetown. Applied for and won scholarship to Oxford University. Studied philosophy and literature.

Each factoid is rich with information, yet it is their proximity to one another—all these slightly paradoxical bits neatly aligned in a list—that makes them startling. In a scattershot interview that lasts more than an hour, Kesey never offers me a simple or a bland explanation, never allows my mind to begin to wander, never gives me a moment to jot down a general observation when a specific story is at its root. His life, like his fiction, reminds me of the murals of Zak Smith or the “combines” of Robert Rauschenberg: Its majesty derives from the confluence of the mini-units, the way the fascinating details cohere and form a whole that you can see without having to squint.

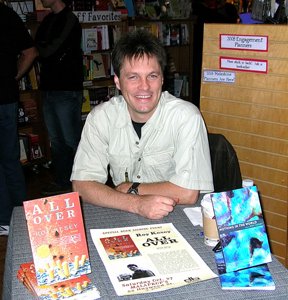

After college, the writer whose “Dispatches” from Beijing are one of the bright spots on McSweeney’s Internet Tendency and who last year signed a four-book deal with Dzanc Books—the first of which, the story collection All Over, was published last October—spent time teaching at universities in France and Peru before accompanying his Peruvian wife to China. “Juan Morillo is a Peruvian writer I really respect,” Kesey says. “He’s been in Beijing for the last thirty-two years.” Kesey, together with his wife, Lu (a diplomat), and two kids, have been here for five.

Kesey answers my questions while enjoying an espresso at Beijing’s Bookworm Café, a setting that’s part-library, part-restaurant, part-performance space, part-bookstore. There are black tables, black faux-wicker chairs, spinning ceiling fans, cabinet-sized Chinese air conditioners in the corners, bookshelves lining the walls, and a mixture of bee-bop, electronica, and rock emanating at low volume from the sound system. I ask him about other Latin American writers he enjoys. “I’m a big Borges fan,” he says, “but I really love [Julio] Cortázar. He’s Argentinean, sort of a half-generation after Borges.”

Until recently, Kesey, Morillo, and others have been atypical members of Beijing’s expat writing scene. The majority of English language books published by Western writers living in China have been of the nonfiction variety. Beijing, despite its cheap food and beer—two dollars worth of Chinese yuan will buy you a nice Chinese meal or a twelve-pack of Tsingtao beer—has yet to become the Paris of the 21st century. In the expatriate cafés that radiate from the northeast hub marked loosely by the embassies and the Sanlitun strip of Western bars—places like Moré (Spanish tapas), Purple Haze (Thai menu, largely foreign clientele) and the Bookworm (French menu café)—you’ll find plenty of writers, but most of them are stringing for the local English language periodicals or posted in Beijing for short stints by one of the larger English language dailies in England or the U.S.

The journalists tend to work hard to master Mandarin—the official language of the People’s Republic of China—but move away once they become successful. For example, in 2004 Ian Johnson published Wild Grass: Three Stories of Change in Modern China (Pantheon) after winning a Pulitzer for his China coverage while working for the Wall Street Journal in 2001, but he’s since been shifted to the newspaper’s Berlin bureau. Similarly, Peter Hessler won acclaim for his books Rivertown: Two Years on the Yangtze (HarperCollins, 2001) and Oracle Bones: A Journey Between China’s Past and Present (HarperCollins, 2006) and landed a gig to write for the New Yorker about China but has since moved to Colorado.

Meanwhile, an expat fiction scene is beginning to emerge in Beijing. Kesey, whose writings range from humorous realism, a la George Saunders in Shanghai, to surrealist postmodern displacement—one of his stories, “Martin,” is the faux-report of a patient “pretending” to be a doctor “treating” an actual guitar string that she “thinks” is a man who thinks he is a guitar string—recently ran a fiction writers workshop at the Bookworm. Jenny Niven, the twenty-six-year-old Glaswegian literary events coordinator at the Bookworm (the café also includes a thirteen-thousand-volume, four-thousand-member English-language lending library), keeps a parade of visiting and local writers marching through its doors for weekly readings. From March 6 to March 21, the café hosted a full-on literary festival: two weeks of panel discussions, workshops, and book signings by China-centric novelists Adam Williams and Catherine Sampson, poets Justin Hill and Edward Ragg, translator Eric Ambrahamsen, journalists Rob Gifford and Melinda Liu, and business writers Tim Clissold and James McGregor, among others.