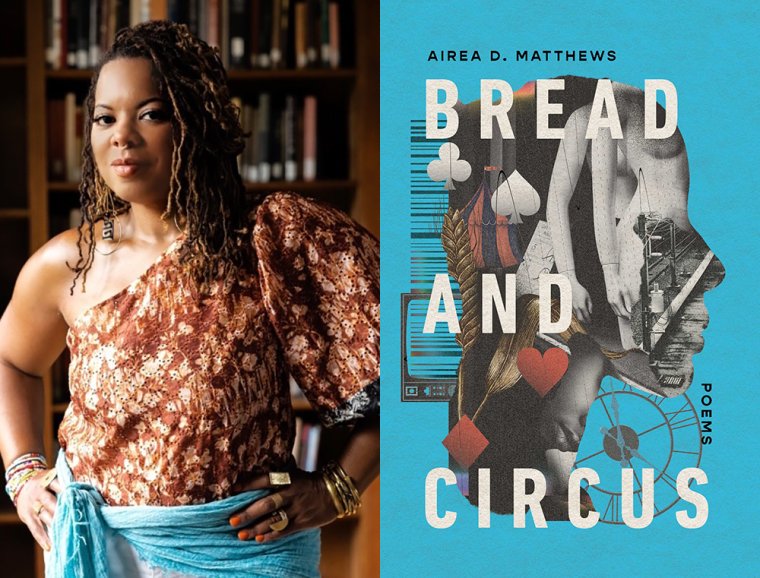

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Airea D. Matthews, whose new poetry collection, Bread and Circus, is out today from Scribner. In this formally inventive book, Matthews deploys a surprising mix of lyrics, prose poems, images, and docupoetic forms to consider the self as a product shaped by individual experience and systemic forces. Adam Smith’s 1776 The Wealth of Nations provides a frame for the collection, which blends autobiography with economic and social theory to examine the origins and far-reaching effects of capitalism and its intersections with race, gender, and class. Smith’s texts appear throughout the book, altered by Matthews to reveal a disturbing subtext about the commodification of human life. Matthews weaves personal narrative throughout the collection, offering insight into how early childhood experiences continue to reverberate into adulthood. Public history, too, repeats in this collection, and Matthews offers a moving portrait of contemporary Black motherhood in poems such as “Animalia Repeating: A Pavlovian Account in Parts,” which recounts the devastating aftermath of the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who killed Trayvon Martin. “I genuflected at Mass, stole fleeting glances of my sons’ hands in prayer—tender, unburdened by veins or violence, unscathed. I prayed that whoever feared them would unlearn myth and threat,” she writes. Publishers Weekly praises Blood and Circus: “Full of humane wisdom, this powerful volume forces readers to acknowledge systemic inequity.” Airea D. Matthews holds a BA in economics from the University of Pennsylvania as well as an MFA from the Helen Zell Writers’ Program and an MPA from the Gerald Ford School of Public Policy, both at the University of Michigan. A fellow with the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, she is a professor and directs the poetry program at Bryn Mawr College.

Airea D. Matthews, author of Bread and Circus. (Credit: Ryan Collerd)

1. How long did it take you to write Bread and Circus?

I wrote Bread and Circus over the course of the last decade. The poems with years ascribed to them are the eldest, and some of the poems, which insinuate othering and isolation, were written during the height of the pandemic. The prose pieces were written in the “in-between” of those two time periods.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The hardest part in writing this book was reconciling what the book wanted to be with what I wanted it to be—personally and structurally. After I wrote my first book, I hoped to write about poverty, race, and class. However, the poems I was writing at that time—none of which made it into the book—felt removed from those concerns. I let time pass to find another way inside my desires. I started reading more autoethnographic work in which the lived experience can be linked to research or cultural phenomena. That simple expansion gave me permission to use my life as evidence and to allow myself to be fully present as a participant in the system.

Structurally, when I originally conceived of the idea of a poetry collection that intersperses economic concepts, I envisioned the extracted texts—what some call erasures—to be actual graphs that I’d honed into poems. However, as I concentrated on certain textual sections from The Wealth of Nations, I wanted to challenge myself to sit with the original text and have some way for the reader to grapple with dual meaning, as I did. To enact that, I decided on palimpsestic poems that require attention to the extracted sections as well as the original text, differing significantly from the true erasure in which the original text is illegible. Another fun fact about the extracted poems is that they are interactive. When held under light (an actual light), the authorial interpretation becomes increasingly clearer, while the legibility of the original text makes it possible for readers to hew their own interpretation.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I tend to consider pondering a form of writing. As such, I write all the time because I am an overthinker. I am constantly questioning, resisting, studying, accepting, and wondering—all of which I believe to be the hallmarks of the writer’s life. As for the physical act of writing, I jot something down every day—whether it’s a memory, an account, a feeling, or something I saw that invoked awe, wonder, or terror. I try to write by remembering through my senses what I’ve seen, tasted, felt, heard, or intuited. Notetaking—on the mundane and the supernatural—has become a practice by which I keep time and mind the turnings of my imagination. Now, do I beat myself up when I don’t write? Nope. I just take comfort in living and in a deep knowledge that whatever writing that is meant to come through me will arrive on its own terms and in its own time.

4. What are you reading right now?

I have exceedingly broad reading interests and some rules around how I read. I tend to decompress after writing a book of poems by reading work outside of poetry for a short while. But we are in the midst of such a rich publishing year, I couldn’t resist! I just read Vievee Francis’s The Shared World and Charif Shanahan’s Trace Evidence—both marvelous. My ancestral research has led to reading, and rereading, historical slave narratives and accounts, including: The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Or Gustavus Vassa, The African, Written by Himself; The History of Mary Prince; Celia, A Slave Trial; and a volume of collected works titled Slave Testimony: Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and Autobiographies edited by John W. Blassingame. I usually read something different at night than during the day. Recently I have been reading chapters of How to Be Authentic: Simone de Beauvoir and the Quest for Fulfillment by Skye C. Cleary, Todorov’s Mikhail Bakhtin: The Dialogical Principle, Jay Murphy’s Artaud’s Metamorphosis: From Hieroglyphs to Bodies Without Organs, and Susan A. Glenn’s Female Spectacle: The Theatrical Roots of Modern Feminism.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I believe in organic strategies, and most revelations come late in my making. I realized that the book was spanning about forty-five years [chronologically], and it seemed wise to find an organizing principle to govern the movement. Around the time when I had to structure the collection, I was also studying and listening to John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. A friend of mine is a musicologist, and he explained how Coltrane’s structure was “through-composed.” The through-composition offers a structure in music that insists on the story moving forward and the narrative developing over the course of the piece. As with A Love Supreme, Bread and Circus has four main movements—Acknowledgement, Resolution, Pursuance, and Psalm. Instead of a repetitive narratological structure, the through-composition allows for a wide variance that helps to set, develop, and show an unfolding story.

Also, a dear friend, Sham-e-Ali Nayeem, author of the poetry collection City of Pearls and composer of the electronica album Moti Ka Sheher, guided the poetry sequence by suggesting that I listen to “When Doves Cry” repeatedly. She told me Prince wrote that song in under an hour to round out the Purple Rain album. Something shifted as I listened, and the sequence of the poems clicked into place thereafter.

6. How did you arrive at the title Bread and Circus for this collection?

My second son, a writer and poet who just graduated from college and is on his way to graduate school in Boston, is my first reader. In an elevator pitch for the draft, I shared the major themes (in my view) of the book: the loss of innocence, materialism (commodity), and spectacle. He reminded me of the quote from the Roman poet, Juvenal, “And every thing, now bridles its desires, and limits its anxious longings to two things only—bread, and the games of the circus!” The quote pretty much encapsulates an avenue of the book’s “aboutness.” After my son’s consultation, the working title of the manuscript became Bread and Circus.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Bread and Circus?

The extracted poems, as well as the poems with visual elements, were created in Adobe Illustrator. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed introducing a new technology into my writing practice. I became so much more intentional about space, visuality, and movement. I wanted the poems to simulate spatial movement and momentum by liberal use of open—free—structures and by fully observing the page as a canvas. My impulse as a writer is to economize, and technology provided a space to explore the contours of the page more extravagantly.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Bread and Circus, what would you say?

It depends on how far back in time. If I could go back to that child in 1977, who became a pawn for her troubled father trying to make ends meet, I would announce myself as a future version of her and say, “I know these words aren’t much comfort, but we survive this, and we’ll find a certain beauty in the ash of this chaos.” I’m not sure what the present results would be of that butterfly effect; but I think the younger me would appreciate the heads up.

If I am moving backwards to the writing of these poems, I would simply encourage myself to remain compassionate and hopeful and to embrace the past rather than be embarrassed by it.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I reread Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle and Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. I traveled to the University of Edinburgh to dig into Smith’s letters and archives. I wanted to understand the man who was the author of the free market and capitalism as we know it—a flawed system that undergirds many societal ills and evils. To delve into the archive is to see the flaws in what the world views as a great mind. I saw the flaws in both Smith’s and Debord’s very disparate theories and added my own flaws into the mix. I wanted those moments of extraction to reflect the truth of my reality meeting the truth of their theories.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

I was once advised, “Write the world as you understand it, and take space to constantly question what you understand and why.” When we write from our understanding, we lend agency to our experience. When we question what we understand and why, we make room for growing beyond what we’ve known or lived.