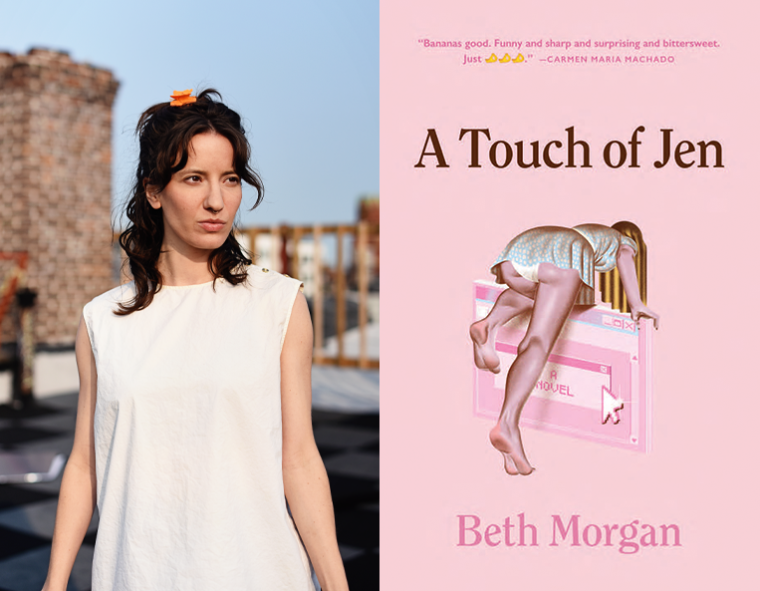

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Beth Morgan, whose debut novel, A Touch of Jen, is out today from Little, Brown. Remy and Alicia, two dissatisfied and asocial food service workers, sustain their deteriorating relationship by fantasizing about a popular influencer named Jen, one of Remy’s former coworkers. The pair obsess over her latest posts, and Alicia regularly role-plays as Jen both in the bedroom and in their daily routine, but their obsession becomes more perilous when the real-life Jen unexpectedly enters their lives. A chance run-in leads to an invitation to Jen’s boyfriend’s place in Montauk, where sexual tension and class conflict are heightened by surfing mishaps and a sleepwalking incident. Even after the trip Jen’s presence looms large, and Remy and Alicia’s lives rapidly devolve in unexpected, grotesque, and terrifying ways. Darkly funny and absurd, A Touch of Jen is an ingenious dramatization of the very real perils of millennial social life. “A Touch of Jen is bananas good,” writes Carmen Maria Machado. “Funny and sharp and surprising and bittersweet. Just [three chef’s kiss emojis].” Beth Morgan grew up outside Sherman, Texas, and studied writing as an undergraduate at Sarah Lawrence College. She recently received her MFA from Brooklyn College. Her work has been published in the Iowa Review and Kenyon Review Online.

Beth Morgan, author of A Touch of Jen. (Credit: Vita Burn)

1. How long did it take you to write A Touch of Jen?

I first had the idea for A Touch of Jen when I was in the Philippines in February 2018, and I workshopped the beginning of the novel that summer in Tony Tulathimutte’s CRIT workshop. A year later I finished my first draft, which I edited through the fall of 2019 and sent out to agents at the beginning of 2020. This whole time I was supported by my partner’s salary as a teacher and by working part-time as a dog-walker, so I was very fortunate in having more time to write than I did when I was working 9 to 5 in an office.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The ending! I wanted the story to go to this specific fantastical place at the end, but there needs to be a certain amount of coherence to any fantasy, even if ultimately what’s important is the emotional impact, not the fantasy’s realism. In the first draft there wasn’t really a full cosmology in place explaining the fantasy, so I had to develop one while also making sure it wasn’t too complex and felt true to the story’s emotional stakes. I also think taking mushrooms helped! Having worked on the book for a year at that point, I had a lot of rigid patterns in place for how I thought about the end, and I think the mushrooms were crucial in helping me to let go of some of those patterns and think about the story in a new way.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I try to write for at least three hours a day and use a timer to keep myself to that, but it’s important for me to be flexible about when and where I write, since there are so many ways that writing rituals can be disrupted. Most of my writing is done at home, either at my standing desk or sitting on my couch, but I’m constantly taking notes on my phone while I’m out and about.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading a lot of Patricia Highsmith. I actually hadn’t read any of her work before I wrote A Touch of Jen, but almost immediately people started comparing my work to hers. I definitely feel a kinship with her for better or worse!

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Elizabeth Gaskell! She’s often overlooked in favor of other Victorian novelists, but her works are ambitious, psychologically insightful, and deeply concerned with class and class conflict in a way that feels relevant today.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I had mostly finished my book before I began my MFA program, so it probably didn’t make a big difference in getting published. However, I did study creative writing as an undergraduate at Sarah Lawrence, so fiction workshops and craft classes definitely had an impact on me. For example, one of my writing professors, David Hollander, directed me toward Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, which was a big influence on A Touch of Jen. And studying writing as an undergraduate helped prepare me for many years without any kind of connection to writers or a writing community because I had developed the ability to write on my own without a program.

Of course I’m also grateful for many of the workshops I’ve been in more recently, including Tony Tulathimutte’s CRIT workshop and my Brooklyn College workshops with Joshua Henkin and Madeleine Thien. Tony is a very thoughtful reader and also gives amazing practical advice and assistance in navigating the publishing world. Josh and Maddie are also great readers, and as my thesis advisor, Maddie has given me so much love and encouragement as I’ve struggled with my latest project.

As a more “experimental” writer, I’m not really interested in the American realist short story, which is of course the dominant genre in a lot of the classes and programs I’ve been in. I’ve definitely found it useful to think about how these kinds of stories work, but I agree with Matthew Salesses, the author of Craft in the Real World, that the kinds of assumptions underlying this genre can be pretty limiting and can make writers unnecessarily second-guess themselves. I’d definitely recommend his book to anyone thinking about an MFA—both as a way to think more freely about their own writing and also as a way to become a better reader.

I think what I’ve appreciated the most about my MFA program is having the opportunity to share my work with a wide spectrum of thoughtful readers. It’s given me a better idea of the kind of reception I can expect for my work and of the extent to which certain ideas are or aren’t coming through.

I definitely don’t think anyone should go into debt to go to an MFA program. Not only is debt horrible, but there are so many great programs that are inexpensive or fully funded, which also means that these programs are able to attract a more diverse cohort. Brooklyn College doesn’t have the big names of NYU or Columbia but the professors there are brilliant and deeply care about their students.

7. What trait do you most value in your editor (or agent)?

From my first phone call with my editor, Jean Garnett, I felt like she just had this perfect understanding of what I was trying to do with my work. The personal essay she published this spring in the Yale Review has the kind of psychedelic intensity that I’m aiming for in my own writing, so I feel very privileged to have her as a reader.

8. What, if anything, will you miss most about working on the book?

One of the most enjoyable parts of writing the book were the supernatural text messages. They were inspired by a scene in Olivier Assayas’s movie Personal Shopper that I thought was really exciting, so when I was writing those text messages I felt like I was recapturing some of my excitement as a viewer.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

My partner, David. He’s believed in my work so passionately for so long but is also very blunt if he thinks something isn’t working. So I feel very confident that he won’t sugarcoat criticism or hold back if he thinks that my work is falling short of my vision.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

My senior year at Sarah Lawrence, I took my first-ever art class—a sculpture class with Joe Winter. Before I took his class, I thought that people who “got” art had a special X-ray vision that allowed them to know if art was good or bad or interesting, and I thought that I didn’t have access to that. I expressed those insecurities to Joe—who I think was confused but was very patient with me. I kept on asking, “What about a jar of vomit, is that art?” And he kept saying, “Are you referring to a specific jar of vomit?” I was hoping he could just give me some straightforward criterion for determining if something was good art or not.

His response was basically, “If what you’re trying to express with a work of art is a discrete meaning, we have words for that, so you would just say the meaning.” Maybe because I was so used to the standardized testing culture of Texas, it didn’t occur to me that engaging with art doesn’t have to be about understanding something or getting the right answer. I think Joe helped me to get more in touch with the ways that I was responding to art and literature independently of its “meaning.” And it changed the way I approached my writing as well. It helped me feel confident in making work that felt more sculptural, that was aware of the variety of artistic responses I could get from a reader without feeling the need to impose on the work a straightforward interpretation or meaning.