This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Dean Rader, whose new book, Before the Borderless: Dialogues With the Art of Cy Twombly, will be published next week by Copper Canyon Press. In this extended exercise in ekphrasis, Rader presents lyrics, prose poems, and experimental forms that interrogate the artwork of the eponymous American painter, sculptor, and photographer. Bright images of Twombly’s creations appear throughout the collection followed by Rader’s response. The poems meditate on Twombly’s use of color and imagery and the philosophical questions raised by each piece as well as speak to Twombly himself in letters addressed to the artist. “Dear Cy, / The beginning of writing is rupture, / a shattering into letters: // what if all writing is a form of betrayal?” Rader writes. The collection considers what it means to be an artist, the connections between visual art and poetry, and the way art can function as a mirror for the audience, becoming a tool for self-reflection. Dean Rader has authored or coauthored eleven books. His debut poetry collection, Works & Days (Truman State University Press, 2010), won the T. S. Eliot Poetry Prize. A professor at the University of San Francisco, he has won fellowships from Princeton University, Harvard University, the MacDowell Foundation, and the John R. Solomon Guggenheim Foundation.

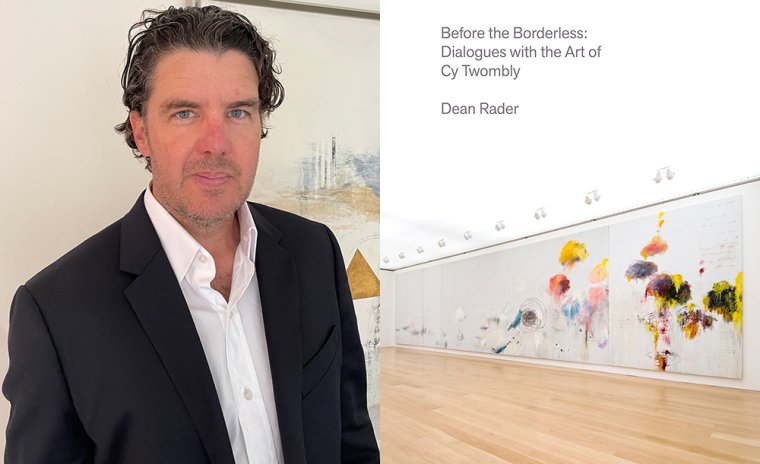

Dean Rader, author of Before the Borderless: Dialogues With the Art of Cy Twombly. (Credit: Jill Ramsey)

1. How long did it take you to write Before the Borderless?

One answer: roughly fifty-five years! I feel like my whole life has led to this. But a more reasonable response is somewhere around five years. I wrote the first poem in 2018, a couple of months after my father died. My sister and I spent an entire weekend going through his effects, and as we unpacked photos and awards and memorabilia and plaques, I kept asking the same question: What makes a life? Not long after that, I went to a career retrospective of Cy Twombly’s drawings in New York City and, in much the same way, started thinking about his work as his “effects” and asking again: What makes a life? That evening, I left the gallery and walked the length of the High Line thinking about everything—my dad, my kids, Twombly, art, how we as humans contribute. It was a lot. That night in my hotel, I started working on what would become the first poem in the book.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I wish there was only one thing! The whole project was challenging, but rewarding. Writing poems that talk to abstract art can be really disorienting, especially when that art appears to be nothing more than scribbles. I also felt challenged to do the impossible: make the poems as engaging, awe-inspiring, beautiful, maddening, and provocative as the Twombly pieces themselves. I knew that would be fruitless, but I had an aesthetic (and an ethical?) calling to do the art justice. I did not want to copy Twombly’s art or emulate it or even explain it, but I wanted to channel its awesomeness. I set myself this task: Could I recreate Twombly’s aesthetic energy—the overall feeling of the artwork—in my poem? Could I do on the page what Twombly does on the canvas? And then, of course, there were practical matters like permissions, tracking down high-resolution files, finding the right files, convincing my press to invest in this project. I can’t thank Copper Canyon Press and the Cy Twombly Foundation enough. Both were amazing.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

That sort of depends on what I’m writing. Most of Before the Borderless was written during the pandemic, at various spots in our house, sometimes at 3:30 AM, when I was freaked out about our world. If I’m writing a review or an essay or a critical article—especially one on deadline—I write every day, keeping regular hours. I love to write in my study in our house in San Francisco. I have a view of the Pacific Ocean which makes everything feel insignificant—and therefore doable.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m doing a kind of reading tag team, between Cormac McCarthy’s The Passenger and Louise Erdrich’s The Night Watchman. I’m enjoying both for different reasons. Also, Victoria Chang and I write a regular collaborative poetry review column for the Los Angeles Review of Books, and at the moment, we are reading some wonderful books of poetry from Wesleyan University Press.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I feel like there were a lot of strategies. Let’s hope some work! The book is divided into four sections. In the first and third, each poem is in conversation with a single Twombly image. Thanks to Phil Kovacevich, the amazing designer, readers are able to experience that conversation in real time. By this I mean, when you open the book, you are looking at a Twombly image on the left-hand page and my poem on the right-hand page. You can see the interplay right in front of you. It is sort of magical.

Sections one and three begin with companion poems on really breezy topics like death, loss, and parenting, each of which talks to paintings from Twombly’s Orpheus cycle. The poems in these sections tend to be short, lyrical, and somewhat elliptical. Sometimes how the poems appear on the page mimics what Twombly is doing on his “page.”

Section two features longer poems that are inspired by entire Twombly series. For example, there is a rather long and somewhat messy poem that responds to Twombly’s Letters of Resignation, which is basically a series of experimental erasures. My poem, which is sort of experimental in form, explores a range of topics from climate change to etymology to what it means to resign to the global refugee crisis. It asks big questions about larger notions of erasure in a form that is kind of erasing itself.

On the other end of the spectrum is a pretty tight poem in ten parts that engages Twombly’s epic ten-panel cycle Fifty Days at Iliam. In this poem, the last line of one section becomes the first line of the next section. The poems are stitched together in a way that evokes the interplay of Twombly’s panels. The fourth and final section, written at the suggestion of my editor, Michael Wiegers, is a kind of epilogue that explains the project and the contexts surrounding its origin and completion.

Overall, my strategy was to do in a book what Twombly does over the course of his career by calling attention to micro gestures and macro concerns. Twombly loved the marriage of text and image. I want my book to celebrate that love.

6. How did you arrive at the title Before the Borderless for this collection?

Great question. That line appears toward the end of the penultimate poem in the book. Carol Edgarian, one of the editors at Narrative, had suggested that as a potential title for a group of poems the journal published. Ultimately it emerged as a favorite title for the whole collection. The runner up was “Field of Incident,” which is the term Frank O’Hara used to describe a Jackson Pollock painting. But that sounded too harsh. However, I do think I want a T-shirt with that phrase on it.

Also, there is something about standing in front of a Twombly painting, like the huge Untitled at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art or Untitled (Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor) at the Menil Collection that makes you feel like you are in the presence of the infinite. The title also echoes a line and a sentiment from Rilke’s great ekphrastic poem “Archaic Torso of Apollo”: “from all the borders of itself, / burst like a star: for here there is no place / that does not see you.” Great art expands beyond its borders.

So many of the poems in this book live in the liminal spaces of life, death, art, the endless—I mean, my father’s death was the genesis of the book, and my mother’s death last year came just as I finished it. The collection is, literally, bookended by their passing. But their lives and legacy are limitless. Borderless.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Before the Borderless?

That Twombly’s work never stopped generating inspiration and ideas. I never tired of it. I could write another book. And another. And by that time, I’d just be getting started.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Before the Borderless, what would you say?

Oh man. Maybe something like: You don’t have any idea what you are in for. But probably: Visit your parents.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I read a great deal of art criticism on Twombly—reviews of exhibits, scholarly essays, aesthetic appreciations. I also passed many days of the pandemic tracking down affordable volumes of Twombly’s catalogue raisonné on eBay. I spent hours poring over his work, tracing his career, looking for patterns and obsessions, taking a lot of notes. Big thanks to the interlibrary-loan folks at the University of San Francisco libraries for their tireless efforts on my behalf.

Also, as I suggested above, there was a great deal of archival work required. For example, the Cy Twombly Foundation granted permission for me to use all of the images, but most of the pieces are also in museums. So I had to get a secondary permission from the galleries and museums for many of the drawings and paintings.

There are a couple of pieces in the book that are not in any museum or gallery, and the foundation did not have high-resolution files of the images. So I had to put on my detective hat and track down high-resolution images. In a couple of cases, that led me to Europe. In one instance, I had to use my German to communicate with an art-storage facility. I’m still in shock it all worked out. The book is so beautiful.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

I had a wonderful poetry professor in college, William Virgil Davis. I remember he told our poetry workshop that when he finished a poem, he would put it in a folder, write the date on it, and put it away where it sat for a year. A full year! When a year was up, he would go back to the poem. If he thought it was successful, then, and only then, he would send it out for publication. I don’t possess that level of discipline. But that lesson taught me to be patient, to let the poem percolate, ferment. Allowing the poem sit a while also allows me to uncouple from it emotionally—at least some—so that I can re-engage it more like an “editor” than a “creator.”

The other bit of advice I tell myself—and my students— is this: Your voice is your voice. Your voice. No one else’s. If a writer can really believe and live that, they have already succeeded.