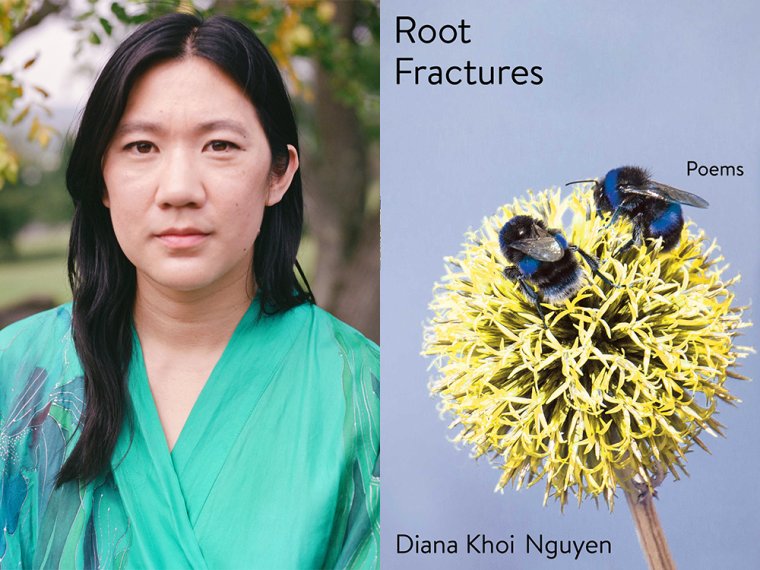

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Diana Khoi Nguyen, whose second poetry collection, Root Fractures, is out today from Scribner. The mix of lineated verse and prose poems—many of which appear in sections staggered throughout the collection—alongside concrete poems creates a collage-like portrait of one Vietnamese American family’s formation, breakdown, and fraught survival in the United States in the wake of the Vietnam War. The poems shift tonally from expository to lyrical, weaving the speaker’s own impressions with overheard speech, bits of historical information, images, and other kinds of language—in both English and Vietnamese—capturing the fragmentary nature of contemporary life, particularly for those from diasporic identities and survivors of trauma and loss. Terrance Hayes praises Root Fractures: “This astonishing second collection renders poetry into an act of kintsugi, embellishing what is broken in a family’s legacy so that it can be held in a new light.” Diana Khoi Nguyen is the author of Ghost Of (Omnidawn, 2018), which received the 2019 Kate Tufts Discovery Award and a Colorado Book Award and was a finalist for the National Book Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. A Kundiman fellow and member of the Vietnamese diasporic artist collective, She Who Has No Master(s), Nguyen teaches creative writing at Randolph College’s low-residency MFA program and is an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh.

Diana Khoi Nguyen, author of Root Fractures. (Credit: Karen Lue)

1. How long did it take you to write Root Fractures?

I think it happened over various intensive writing sessions, roughly thirty days each year between 2017 and 2021. It’s funny: In early 2021, I’d known that I had enough poems for a new book, but the thought terrified me; so I printed them out, stuck them in a translucent folder, then proceeded to travel with the unordered manuscript for over a year—while actively avoiding engagement with the manuscript. It wasn’t until I gave birth in June 2022—and moved back to the area where I was born and grew up (perhaps not unlike salmon returning home to spawn), left the infant with my parents, drove to my childhood public library (where I spent hundreds if not thousands of hours in my youth), and laid out the pages on a conference table—that I sculpted the book into being.

This long gestation period revealed to me, retrospectively, that I needed to take care of a human entity (and also conceive and spawn one first) before I could focus on the next book. I had never planned on becoming a parenting body and being.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

A similar thing with the first book: Did I give fair treatment to the living (and deceased) members of my family without making concessions in my own truths? It’s so hard to balance family and one’s work, especially when we do not view shared history in the same way. I think the gestation period was longer than I had anticipated because I hadn’t yet figured out a curated experience that felt right with respect to family fairness.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write for fifteen-day periods, twice a year, with close friends across genres and disciplines. Initially it began as practice of writing thirty poems in thirty days, to put myself into a pressurized situation to write again after completing an MFA and working tiresome full-time office hours in the years post-MFA. Since then I’ve revised the intensives into more fruitful chunks—and the best part of these sessions are the people I invite to write/make alongside me. It’s so inspiring to witness others drafting and creating each night, all of us sharing vulnerable offerings, only to start again the next day.

4. What are you reading right now?

Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, who is easily one of my favorite living writers. As with anything that is a favorite, I’m savoring each sentence, each page, going back to start again at the top of the page—as if to make the moment last a little longer—rather than ravenously devouring the book, which is how I normally read (and also physically eat, ha!). I’ve also just started Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino, who activates, delights, and stimulates my brain with each clause of her sentences—not to mention how the science-oriented elements of her novel are nourishing a deep thirst in me.

As for poetry, I’m also reading Paul Hlava Ceballos’s banana [ ], which feels urgent, innovative, and essential. And Claire Wahmanholm’s Meltwater, which keeps me rapt even though I’m reading it again for the fourth time—it taps into all my intersecting concerns and anxieties: parenthood, grief/loss, fear about climate change and the alarming signs our environments reflect back to us.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

A primarily intuitive one. The collection consists of many long series, which I didn’t want to stack back-to-back. So I knew I would break them all up—and I even broke up poems that weren’t sectioned—so that I had patches to work toward a quilt, or various threads to weave into a larger whole. From there I made decisions about how to enter the collection and how to close it out. Then: What were the movements? How many sections would there be, and how would those sections open and close, etcetera? The best part was figuring out what to cut/carve, since I had so many pages of potential pieces to include. I love seeing how much hair is on the floor after a haircut and, because I love metaphors, (I can’t remember who to credit for this one) to see a poem or book as an iceberg: So much lies underwater. As readers, we only see just a small percentage of the ice above water.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Not necessarily. Only if they’d like to have the maybe-terminal degree. I say “maybe-terminal” since some consider creative writing PhDs to be more “terminal” than the MFA alone. And only if they need institutional structure—with its pros and cons—and attendant community and resources. Usually most writers do want all of these things. But it’s certainly not necessary to hone one’s craft as a writer. And! I also recommend that writers consider low-residency MFA models, which I didn’t know about when I applied for MFAs; I love the intensive mentorship that low-res models offer—that one-on-one attention and correspondence. It feels more helpful to me, as an introvert, than the sometimes impersonal (if not sometimes hostile or apathetic) workshops with semi-strangers. That said, I don’t regret my own MFA journey—but I wish I could have tried other ones too! Perhaps in the multiverse.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Root Fractures?

How hungry I was to write prose in blocks! But that shouldn’t have been surprising, since the triptychs in the first book employed elements of writing in a text-box block—just with the interruption of the collaborating family archival images. Honestly, Jenny Erpenbeck’s Visitation inspired me to write long, winding sentences that surprised me with each clause and turn. What a gateway! And now I’m writing prose for whatever this new autobiographical prose project will turn out to be.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Root Fractures, what would you say?

This is pretty random: I’d remind myself to look up “root fractures” in a search engine and spend time with all those X-rays of damaged teeth! Of course that’s what root fractures are in other realms (chiefly dental)—I hadn’t realized until after the manuscript was well on its way to becoming a book. It wouldn’t have changed my experience of assembling and titling the book, but I wish I had incorporated that into the creation of it.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Oh, so much video work! And listening to others in the Vietnamese diaspora—folx who have generously sat with me and shared their responses to my open questions. I made a point of trying to connect with folx of Vietnamese descent in my various travels for work so that I could listen to their narratives and experiences. I wanted more voices in my mind—to add to the ones I know/knew so well.

As for the video work, I had been engaging—and continue to engage—with family home videos, crafting short experimental documentaries, or video-poems, which sometimes have audio, text, or neither. Surprisingly, or not so, it was especially helpful to work with crafting multi-channel video pieces. (The learning curve for Adobe Premiere is so high! But I’m grateful I now have access to the program through an employer.) Something about learning to sequence through multiple video channels really transforms how I think about juxtaposition, overlap, and order in both poems and manuscripts.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

It’s deceptively simple: Don’t stop writing, no matter what. Which is easier said than done. I have wanted to give up so many times—especially before I established my close inner community. I don’t even remember where I heard this advice—maybe from someone on a panel at a university somewhere—but it’s stayed with me. I share this advice with others. Never not write. Find a way to carve out space/time for this essential practice, which can be so excruciating at times (both the carving out of space and also the act of writing). And yet it does feel so good to have written, right?!