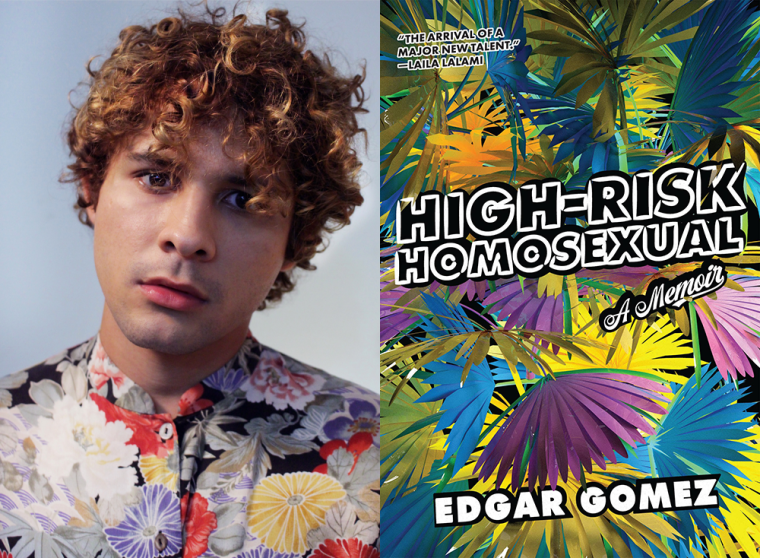

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Edgar Gomez, whose debut memoir, High-Risk Homosexual, is out today from Soft Skull Press. In the first chapter of High-Risk Homosexual, Gomez recalls a trip to Nicaragua at thirteen in which their uncles attempted to curb their queerness and train them to be a man. But Gomez admits the mission was not one-sided: “What would always nag me, though, beyond anyone else’s complicity, is my own. As much as my family wanted me to be a man, I wanted it more.” Here and throughout the memoir, Gomez reckons with both the world and themselves, examining their memories and identities with unique tenderness and honesty. Back home in Florida, and later in California, they continue the difficult work of becoming. Always questioning and seeking, they model how to embrace and build a queer future. “High-Risk Homosexual is a keen and tender exploration of queer identity, masculinity, and belonging,” writes Laila Lalami. “Edgar Gomez writes with honesty and humor about the difficulty of straddling boundaries and the courage of finding oneself.” Edgar Gomez is a Florida-born writer with roots in Nicaragua and Puerto Rico. Their writing has appeared in numerous publications, including Longreads, Ploughshares, and the Rumpus. A graduate of the MFA program at the University of California in Riverside, they live in Queens, New York.

Edgar Gomez, author of High-Risk Homosexual. (Credit: Joseph Osborne)

1. How long did it take you to write High-Risk Homosexual?

I worked on it off and on for around seven years, which sounds wild, but a lot of that time I wasn’t sure what I was doing, and I was still trying to figure out how to tell a story. When I started I didn’t know about things like plot, or characters having motivations, or stakes, or structure, or how to manage time, or really anything. It was a learning curve. One of the reasons it took so long is because those things weren’t discussed in many of the early nonfiction creative writing classes I took, which was a real disservice to me, because those are tools that every memoirist needs to know, not just novelists. Don’t get me wrong, we did have some useful conversations about ethics, about research and stuff like that. But that was all big picture. I needed to know what a scene was first. I was totally lost during many of those years.

2. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

Oh god, this is something that I used to be super embarrassed of that now makes me proud. So when I say the book took around seven years, it’s because I’m counting a few chapters that I started writing while I was an undergrad. One of them is “Boy’s Club,” which is about a night I went to a gay bathhouse when I was twenty-one. I remember that at the time I wrote that story, I needed to come up with something for this creative nonfiction workshop I was in. I really wanted to go to that bathhouse, but I was too afraid and had a lot of shame around my queerness, so I sort of used the workshop as an excuse. In my mind, I was like, “Okay, I’ll get to see what it’s like there, but I’m going to treat this like it’s journalism.” That way, I’d get to go, and I’d also be able to pretend like it was just for the assignment and maybe that way my classmates wouldn’t judge me. Even so, I wasn’t that naïve. I knew some people in my class would still probably judge me. I knew they’d see through my little act. That’s what I’m proud of. That I did it anyway.

3. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Figuring out my intended audience! Early on I wanted it to do too much for too many people. I was trying to satisfy my classmates in my workshops, all queer folk, all Nicaraguans, all Puerto Ricans, all Latinx folk, the publishing industry....There are so few queer, Central American memoirists. I felt this pressure to represent us all, and I also thought, “If this isn’t successful, when will another one of us get the chance?” Part of that is valid, but another is actually quite egotistical of me. I mean, I struggle enough representing myself. Once I realized that this book couldn’t be everything for everyone, that it was unreasonable to put the weight of the entire industry on myself, I was free.

4. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Wherever I can, whenever I can, and as often as I can. In the beginning I wrote a lot at Starbucks and cafés, because I still lived with my mom, or else in extremely loud environments and I found more peace there. That, or I was working several jobs and hardly ever home, so I treated them as little writing sanctuaries between shifts. For that reason, it bugs me when I hear people make fun of “Starbucks writers.” It’s like, okay? You have stability and a nurturing space to write? Is that not enough? Why do you have to come for people who don’t? That was where I wrote before the pandemic. Now I mostly work in my bedroom with the door closed. I need to write something, even if all I do is tweak a sentence, at least twice a week, or I start getting this itchy feeling in my brain. My ideal writing session begins at around noon and runs about five hours, which is when I start getting lightheaded because I probably haven’t eaten.

5. What are you reading right now?

Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde and I’m Not Hungry but I Could Eat by Christopher Gonzalez. I’m taking in Sister Outsider slowly because Audre Lorde packs so much into her writing and I don’t want to miss anything. I like to chew over her ideas for days. I’m Not Hungry but I Could Eat is a collection of short stories about bisexual Puerto Rican men. Reading it a little faster, but also definitely don’t want to miss anything....

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Minda Honey. Her forthcoming memoir, An Anthology of Assholes, is going to be everywhere—trust. Vulnerable. Heartbreaking. Hysterical. Nuanced. Compulsively readable but never easy. What Minda does with words is magic. Know her!

7. What trait do you most value in your editor (or agent)?

Both my editor, Sarah Lyn Rogers, and my agent, Danielle Bukowski, are genuinely good people. Sarah is especially patient with me. Maybe I think that because I’ve been socialized to feel like a burden, but she always takes her time to walk me off the edge when I start panicking and is all-around reassuring. Danielle is great and so supportive. One of the first things she told me when I met her was that she’d never ask me to write about trauma. Oddly, that made me more comfortable writing about trauma. In general I’ve had a lot of anxiety around publishing because I’ve internalized the gatekeeping that’s been put in place to keep people like me out. I’ve worried about being perceived as difficult to work with for objecting to anything, or “risky” because of what I write about or trivial because I use humor in my stories. But they’ve always had my back.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started High-Risk Homosexual, what would you say?

Your writing is important, but it’s not the most important thing in the world. Make sure to prioritize other parts of your life, too, especially your friendships. Your words can only support you so much. That, and don’t stress about the rejections. In retrospect I’m grateful for nearly every story rejection I’ve gotten. Those stories weren’t ready. I write much better now.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I’m grateful to be in a writers group with Minda Honey, Natassja Schiel, Asha French, Elizabeth Owuor, and Natalie Lima. They’re the only people I’m showing my early drafts to right now. There’s a lot of reasons why I trust them, but number one is that I respect their work. I love what they write. I truly enjoy their art. I don’t take that for granted. You have to be in community with people you admire.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I can’t remember who said this or in what context, but it’s something I think about a lot, especially when I’m writing something I’m worried will never make it beyond a Word doc on my computer: “You have to make yourself undeniable.” I like that it acknowledges that not everyone will love your work, but at the same time asks you to make it so good they can’t reject it.