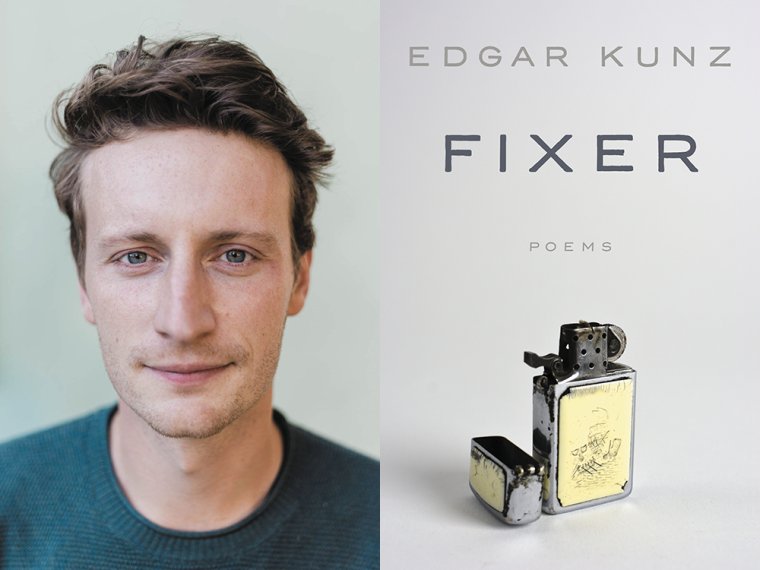

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Edgar Kunz, whose new poetry collection, Fixer, is out today from Ecco. At the heart of this touching group of narrative lyrics, a young man grapples with the legacy of a troubled father. In the long title poem that forms the backbone of the collection, the speaker breaks into his deceased father’s apartment, attempting to make sense of the troubled man’s life through the objects he’s left behind: “Your coat. The cash in your pockets. / The cellophane from a fresh pack. // Zippo with a carving of a whale, / proud ship in the distance.” On either side of this monumental event, the speaker finds himself navigating his own troubles and struggling to exceed the limitations of class, gender, and family history. The collection opens after the speaker has abandoned a lover and fears that this transgression has fulfilled a pattern of toxic masculinity that deserves punishment: “I wanted / to be revealed by some visible sign // a welt to ride the ledge of my cheek,” Kunz writes in “Day Moon.” But the speaker is too self-aware to fall into mere repetition compulsion, and the collection offers a window into a psyche awakening to the power of will against destiny. Attention to beauty, to love, and to art demolishes the fear and shame that cover our better natures: “Where they pry // the rotten timber away, / the brick is a brighter / shade of red beneath,” Kunz writes, narrating a neighbor’s home renovation project in “New Year.” Edgar Kunz is the author of Tap Out (Ecco, 2019). He has received support from the National Endowment for the Arts, MacDowell, and the Wallace Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University. His poems have appeared in the Atlantic, the New Yorker, Poetry, and elsewhere. He lives in Baltimore and teaches at Goucher College.

Edgar Kunz, author of Fixer. (Credit: Ariana Mygatt)

1. How long did it take you to write Fixer?

After my first poetry collection, Tap Out, I struggled to write—a few flashes here and there, but mostly the poems were terrible! I wrote almost nothing worth saving for more than a year. Looking back, it’s obvious why: I was avoiding my subject. Just before Tap Out hit the shelves, my dad died. He was an addict in free fall, and I’d been grieving him a long time. But then he’d actually gone and died, and with him went the potential for reconciliation. I went home and buried him and cleaned out his apartment with my brothers and went back to my life. It took time to find the courage—and the required distance—to write about it. And one day I wrote a little poem about breaking into his apartment, and then another one about where I think I might have been when he died, and another one about the last time my brother saw him. I couldn’t stop. I wrote the middle section of the book, a long poem called “Fixer,” then filled in around it with love poems, weird-job poems, and poems about artificial intelligence, urban gardening, and trying to find a good therapist. I wrote most of the book in a month.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I struggle to write well when I know the subject of the poem going in. Once the book started to show itself, it became clear it needed a bit of narrative clarity here, a bit more elaboration there. There were holes I needed to fill, threads I needed to develop. That was hard for me. The poems often felt didactic, corny. The book ended up being quite short—about seventy pages—because I cut every poem that felt willed or predictable.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I have very little discipline. Even when writing is going well, I’ll go weeks and weeks without writing a word. I have very little discipline: Barf. What I mean is, my process has, so far, been inconsistent. Bursts followed by fallow periods. I’m trying to get better about accepting that. I used to believe it was about clocking in and hammering out your drafts. I mean, it’s important to take the work seriously, but don’t trap yourself into false models of production and worth. Reading is writing is something people say, but also dinner with friends is writing. Going on long walks is writing. Laying down is writing. You can go long periods without setting down a word and still be gathering the necessary materials, storing up energy.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m halfway through Eula Biss’s Having and Being Had, and it’s fantastic; I’m a huge fan. I’m rereading Victoria Chang’s The Trees Witness Everything—brilliant. Books out this year I’ve read and loved include Megan Fernandes’s I Do Everything I’m Told, Alina Pleskova’s Toska, Maggie Millner’s Couplets, and Thea Brown’s Loner Forensics. Will Schutt’s translation of Fabio Pusterla’s Brief Homage to Pluto and Other Poems is excellent too.

I’m also reading The Lord of the Rings with a group of friends. We’re all trying to read the trilogy at the same pace; I think we’re set to finish in October. Our pal Danny is a de facto Tolkien scholar, and he very kindly fields our questions about wraiths and wizards and the durability of hobbits. Super fun.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I didn’t know I was working on a book until I wrote the middle poem, a series of eighteen-line sections exploring the period after my dad died. Once that was done, I had to sort out a middle and an end. I had a couple of poems on hand I liked, including “Day Moon” and “Night Heron,” the two earliest poems to make it into the book, and I knew I wanted to write more about work and labor, falling in love, building a life in a new city. Soon I had two hinge poems that led into and out of the long middle sequence, “Squatters,” which ends with the mother calling to tell the speaker about his dad’s death, and “Tuning,” an aftermath poem that follows a section featuring a piano tuner. After that, it was a matter of writing drafts and grouping them by intuition into first-section poems and third-section poems. Eventually, after much shuffling, an order revealed itself, and I stuck with it.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Sure. The MFA gives you time to write, a boost to your sense of yourself as a writer (important!), and a group of smart people who also care about writing and who hopefully want to help each other get better. Graduating with a book manuscript would be great, but the real goal, I think, is simply to improve and to lay the groundwork for a writing life. If you can find one friend in your program whom you trust and who can commit to exchanging work with you regularly after the MFA, you’re golden. And don’t go into debt for it if you can help it. If you can quit your job and move to a new city, I’d only apply to full-residency programs that offer full tuition remission and pay you enough to live on. If you can afford it and/or can’t move, low-residency programs can be a good option. Ask about scholarships.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Fixer?

I’m surprised by how rangy the poems ended up being. They’re funny and weird and hopeful and tragic. I’m proud of my first book, but it’s not exactly a barrel of laughs. I think I pulled off something more tonally complex in Fixer. It’s truer to the texture of my life.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Fixer, what would you say?

Read more. Drink water. Call your friends. Spend less time worrying about not writing and more time doing things that bring you joy.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

In the years between publishing book one and starting book two, I took on a series of escalating home-improvement projects. I don’t know if I had to do them to complete the book, but I wasn’t writing, and I still had the urge to make, fix, take apart, and rebuild. I refinished the hardwood floors in our living room, constructed a series of fences around the yard, got a speaker system for free off Craigslist and repaired it by soldering new capacitors to the board. I’m in the process of replacing all the doors in my house with old solid wood doors with cut glass knobs. Fitting things together in the physical world is so satisfying. I get tired of poetry. The drafting and drafting to get a poem even a little bit right, then undoing it the next day and starting over. I live behind a Subway, and one day one of the guys who works there came out and slapped the fence I built and said, “Nice fence.” I was so happy.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Louise Glück was my teacher during my Stegner fellowship, and she told me once that my poems “tend to achieve a premature polish.” In other words, I can make a poem seem, at first glance, finished—taut, lively, convincing. But often, in early drafts at least, I haven’t yet done the thinking and feeling the poem requires. It was a brutal assessment, but true—and useful. I’m learning to let my drafts be messier for longer, to linger in the exploration and discovery phase.