This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Eloghosa Osunde, whose debut novel, Vagabonds!, is out today from Riverhead Books. A tour de force of magical realism, the novel traces a vivid array of characters in Lagos for whom life itself is a form of resistance: “a driver for a debauched politician with the power to command life and death; a legendary fashion designer who gives birth to a grown daughter; a lesbian couple whose tender relationship sheds unexpected light on their experience with underground sex work; a wife and mother who attends a secret spiritual gathering that shifts her world; a transgender woman and the groundbreaking love of her mother.” Vagabonds! takes us deep inside the hearts, minds, and bodies of a people in duress—and in triumph—in a way that only the best fiction can do. “In Vagabonds! you will discover queer people finding ways to love each other in a society that outlaws queerness, and an explosive portrait of Nigeria that will blow your mind—in prose that feels so alive it practically vibrates off the page,” writes Lidia Yuknavitch. “A masterpiece.” An alumna of the Farafina Creative Writing Workshop, the Caine Prize Workshop, and the New York Film Academy, Eloghosa Osunde has been published in the Paris Review, Gulf Coast, Guernica, Catapult, and other venues. Winner of the 2021 Plimpton Prize for Fiction and the recipient of a Miles Morland Scholarship, she is a 2019 Lambda Literary Fellow and a 2020 MacDowell Colony Fellow.

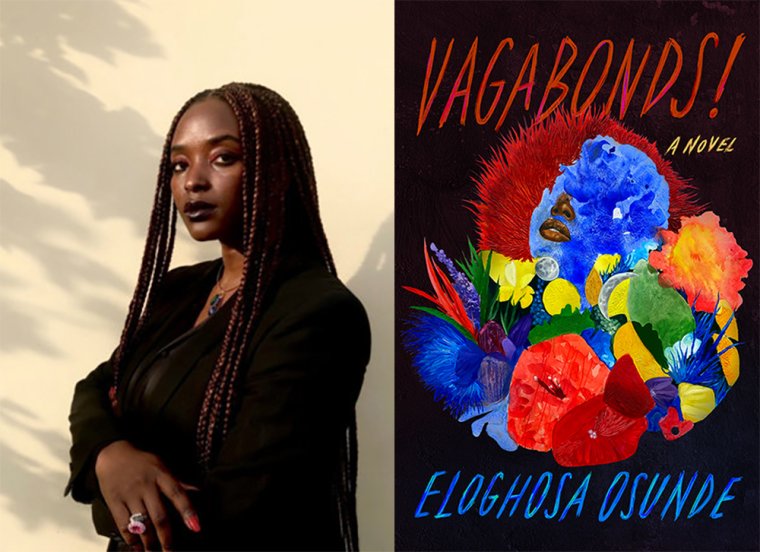

Eloghosa Osunde, author of Vagabonds!

1. How long did it take you to write Vagabonds!?

Mm, my answer could be three years, or five months. I wrote the first short story, “Night Wind,” as a standalone in 2017. I wasn’t trying to write Vagabonds! yet. I’d been working on something else—a better-behaved novel—and that was my main focus, even as I wrote and placed other short stories in publications. A while into doing that, I started to see my work more clearly, and also just paid attention to what I respect and don’t respect in stories, and why. It hit me properly in late 2018 that a book that moves like Vagabonds! is the specific kind of novel I would 100 percent want to enter the world with, and stand by for a long time. I think of that moment as the starting point of the manuscript, the nudge that got me started on sculpting this book. That process took about five intense months and then it was done.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Putting my complete faith in my work and a sure doubt in the voices inside and outside me that wanted me to play it safe. We talk a lot about the role of faith in achieving things, but I also believe in the power of doubt, especially here. So much of the book, so much of what I dared to allow myself to imagine was a direct result of me training myself to doubt certain stories and limitations I’d believed all my life. Doubt is a useful weapon to have on you if you’re in a world that will continue to tell you terrible stories about yourself, just because. It’s good to know who to trust, I’ve been learning, but also who to doubt. Getting a hang of this took time; getting used to the sound of my own voice took time; catching up to my inherent worthiness took time; becoming brave enough to write this book took time. That was harder for me than the writing itself.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Where: I write at home, from my bed or couch, because tables are too serious and I don’t get as much done on them. Taking the pressure off, for me, usually involves a duvet. When: at night, mostly. Or in the dark—a situation I’m able to create in my apartment regardless of what time it is outside. Usually, I’ll have some music or rain sounds playing in the background, AC’s on—always. How often: as often as feels true, which is, at this point, almost everyday.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just finished Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W Moniz. The collection finds such an impressive equilibrium between vulnerability and restraint. I was reading Warsan Shire’s Bless the Daughter Raised By a Voice in Her Head at the same time, which I’d been waiting for since I heard it was coming. I’m going into This Here Flesh by Cole Arthur Riley now. I’m impressed already.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Arinze Ifeakandu. His stories are so particular about their pace, so sincere. There is no hurry there. Even beyond plot, I love admiring the skill it takes to collaborate with silence on storytelling, to let it know that you take it seriously enough to need it too. His book God’s Children Are Little Broken Things, out in June, displays this flawlessly. Preorder it! Logan February, whose poems affect me so personally. Pemi Aguda. Her books are coming.

6. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

If there was something I could change about the publishing industry, it would be the abysmal pay gap that exists because of systemic racism. I think very often about the number of brilliant writers who get told no for vague reasons, who get told There is no market for this by people who begin with the conclusion that white markets are the main (or only) markets. It’s so obvious to me that there are multiple markets active at once, different demographics with purchasing power still heavily un(der)represented in print, and many readers of all sorts of stories who would reach for the books if they were actually there. Money is what allows people to (continue to) write without worry. So, because I’m so tired of hearing about how many writers I love—dead and alive—were severely underpaid for groundbreaking work, even when their names were everywhere, that’s the first thing I’d change. We need more range of experience, people of varying nationalities in positions of power, so that we can get more brilliant, textured stories out into the world. Oh also! I’d make sure people got paid their advance in less than four installments for sure. Three. Two. Whatever. Just not four. Bills are real.

7. What trait do you most value in your editor (or agent)?

Certainty, for sure. My agent, Jackie, met and signed me off just one short story, one essay and a proposal for a novel. I have always appreciated this, because I know it’s the industry norm to wait on the finished manuscript before taking a chance—especially with fiction. She met me and knew. Kristi, who is Jackie’s assistant, has also just made my life so much easier with her sturdiness. Jessica Bullock, my UK agent, is ever ready to do what my journey requires, and my film agent, Kristina Moore, is this way too. The trait I value the most in my editors—Hi Cal! Hi Kish!—is also the same: certainty. Both editors read the manuscript and knew they wanted it exactly as it was, then worked with me on the book from inside that assuredness. I can see what a blessing that has been.

8. What, if anything, will you miss most about working on the book?

Building the world it’s set in. I assembled this world with care, so I know how everything works inside it, even when it appears chaotic. I’ll miss fussing over the mechanics, but thankfully my next book is set there too.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I’m my most trusted reader, because I know all about the knot my interests form when joined together. I really respect my judgment, trust my taste and know I can be honest with myself in the readback about what doesn’t work. If I’m stretched by the story’s unfolding, moved by the places where all those interests overlap, then I know that the work is moving. If I’m not, it’s not. I always know the difference. My friend Joshua Segun Lean as well, who is the most attentive reader I know; my best friend Fadekemi, because she sees me and loved me for fifteen straight years, has been in my life long enough to know my truths from my lies; and my partner, who reads my work from a familiar place, with both seriousness and joy, and shares thoughtful responses that help me connect deeper with the work.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

“Please build heart work into your practice. Tend to your heart everyday and don’t just assume because you’re writing from the heart that you’re tending to your heart… Please please tend to your heart when creating the art our hearts need, the art that helps your family eat. We all deserve healthy hearts. Please believe. I’m trying to believe too.” —Kiese Laymon