This week’s Ten Questions features Erika Howsare, whose debut nonfiction book, The Age of Deer: Trouble and Kinship With Our Wild Neighbors, is out now from Catapult. In this insightful mix of history, folklore, reportage, and personal narrative, Howsare considers the lives of deer and their relationship to humans. “Deer speak to our twin American obsessions with death and its denial,” she writes in her introduction, priming the reader for a nuanced exploration of creatures that she says limn the border between flesh and spirit, nature and civilization. As game, deer have long been killed for sustenance or sport. But they also evoke the numinous and are central to various cultural mythologies that venerate them as psychopomps or heavenly messengers. Howsare explores her own encounters with the animals, as a child living in a community of deer hunters outside Pittsburgh and during recent adulthood as a homesteader in rural Virginia; she takes the reader along on her travels to view cave art and observe folk rituals in which deer are central. “They were wild, a word that comes from willed, as in self-willed: passing their own time on earth,” she writes, confronting the fundamental aliveness that people and deer share. Publishers Weekly praises The Age of Deer: “The prose is elegant…. Readers will be enthralled.” Erika Howsare is the author of the poetry collections How Is Travel a Folded Form? (Saddle Road Press, 2018) and, with Kate Schapira, FILL: A Collection (Trembling Pillow Press, 2016). She holds an MFA from Brown University, and her writing has appeared in the Brooklyn Rail, the Los Angeles Review of Books, the Rumpus, and elsewhere.

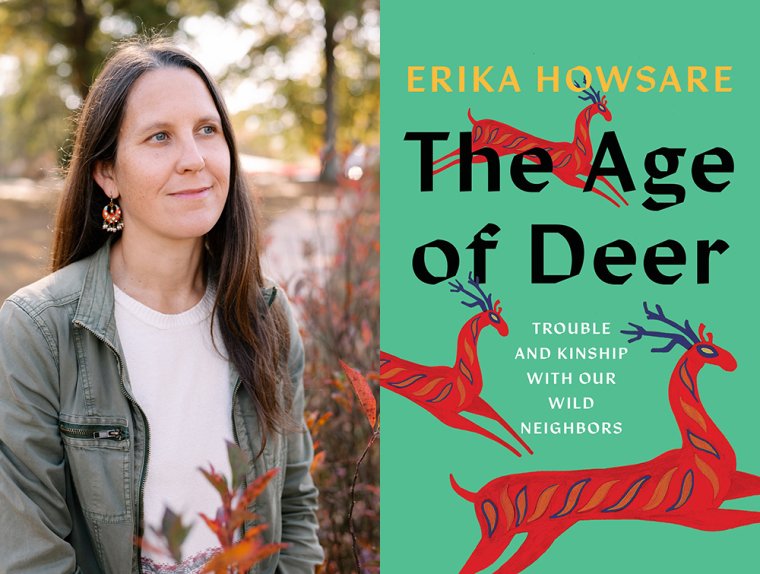

Erika Howsare, author of The Age of Deer: Trouble and Kinship With our Wild Neighbors. (Credit: Meredith Coe)

1. How long did it take you to write The Age of Deer?

This book feels like it arose from a mysterious place; I don’t remember a singular moment when the idea came to me, and I’ve realized that in some ways its roots go back a long way into my life and family history. But in terms of its actual manifestation: I began to put ideas together in 2019 or so and had a proposal drafted by 2020, including several chapters. In February 2021 Catapult Books offered the book a home, and I committed to finishing the manuscript within eighteen months. After I turned it in, it became clear that I would need to make some massive cuts—and revise, of course—and that process took several months in itself. So altogether about four years, although there were some slower periods in the beginning while it was gestating, and again near the end, when it was with my editors.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I’ve practiced hybrid writing for a long time—literary blendings of poetry and prose—but this book is a different kind of hybrid: It’s definitely prose, but it combines journalistic reporting, researched material about history and science, and cultural studies, along with a bit of memoir. Some of those modes are a lot more familiar to me than others, and I had to push through some insecurity at times about tackling the less comfortable subjects. While deer would seem to be a very defined topic, they really contain multitudes, and managing the vastness of the material, making it into a collage that felt coherent, was the major (and very pleasurable) challenge.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I almost always write at home, and in the span of writing this book I graduated from working on my bed or couch to having my own tiny, perfect office: major upgrade. I work best in the morning but that preference always needs to be balanced with the realities of homeschooling two kids, ongoing house and homesteading projects, etcetera. Fortunately, for this book, there was always something needing to be done that wasn’t actual composition—planning, correspondence, etcetera—so if I wasn’t feeling inspired or only had thirty minutes, I could make at least a little progress almost every day. Near my deadline I escaped for a weekend at a rented cottage and worked like mad to polish up the chapters.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just finished Terry Tempest Williams’s When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice and started Amit Chaudhuri’s Sojourn. Also on deck are Olivia Laing’s Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency, Anne Carson’s Decreation, Miranda Mellis’s The Revisionist, and the latest Brooklyn Rail. I recently loved Joanna Pocock’s Surrender: The Call of the American West and Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

I was very lucky to study with Thalia Field in grad school; during her course on deep ecology was the moment when I thought, “Oh, these are my questions, the ones I’ll be working with for the rest of my life.” Her book Personhood (as in the personhood of animals) certainly influenced The Age of Deer. Rebecca Solnit, John McPhee, Joan Didion, Merrill Gilfillan, and Cole Swensen.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

All I can say is that I’m extremely grateful I had the experience of pursuing an MFA that did not result in debt.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

All these folks have been very helpful, but one of the most key pieces of advice came from my editor in the UK, Clare Bullock, who read some early drafts and gently told me to stop writing as though the book would be read by a stern professor. This was so perceptive. In poetry I am, if anything, overconfident. But I realized that in tackling this nonfiction project I had some anxiety about getting it right, and some part of me was back in school worrying about my grades.

8. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of The Age of Deer?

As I said, the origins of the book are obscure to me. I thought I had chosen to do it because it was an interesting topic that would let me ask all these questions and make all these points. By the time I finished I actually felt that the topic had chosen me. Writing the book has led me toward certain ways of being and certain relationships to the world that I now realize I have needed for a long time. Physically and spiritually, it has opened doors of perception. Since deer have often played the role of messenger or guide in world mythologies, this has a pretty eerie resonance.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

There was definitely a ton of research, of both the reading kind (books, scientific articles, news stories) and the experiential kind (I took a number of trips and reported on things like hunting, fawn rehab, and roadkill compost systems). I always had an eye out for deer in stories and art and, of course, real life. Running and yoga and being with my people keep me anchored. I also kept writing poetry throughout the project and took a great course through Orion magazine, taught by Alison Hawthorn Deming, that allowed me to reflect on the writing process more broadly, as did a companion project: making a podcast miniseries called If You See a Deer.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

When I was in college and showed a few early poems to my dad, he told me, very simply, to keep going.