Today’s installment of Ten Questions features Franny Choi, whose new poetry collection, The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On, is out today from Ecco. In these ecstatic lyrics, Choi explores what it means to survive in an era that teeters on the edge of apocalyptic doom. From the specific standpoint of a queer Korean American, the speaker of these poems navigates broad crises: climate change, the global rise of authoritarianism, political polarization, and mass violence in the United States, where people of color, women, and LGBTQ people have seen their rights challenged and lives increasingly at risk. However dire the current moment, the speaker locates herself within a long history of sociopolitical disaster: from the colonial terror of America’s founding to the Korean War to September 11 and beyond. The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On dramatizes the mental whiplash of simultaneously wishing to break free of oppressive systems while reckoning with one’s own complicity in those systems: “Lord, I confess I want the clarity of catastrophe but not the catastrophe,” Choi writes in “Catastrophe Is Next to Godliness.” Publishers Weekly praises The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On: “urgent and lyrically dynamic.... Choi’s electrifying language grips the reader from the first poem and never lets go.” Franny Choi is the author of two previous collections, Soft Science (Alice James Books, 2019) and Floating, Brilliant, Gone (Write Bloody Publishing, 2014). A recipient of the Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, they are a poetry editor at the Massachusetts Review and a faculty member in literature at Bennington College.

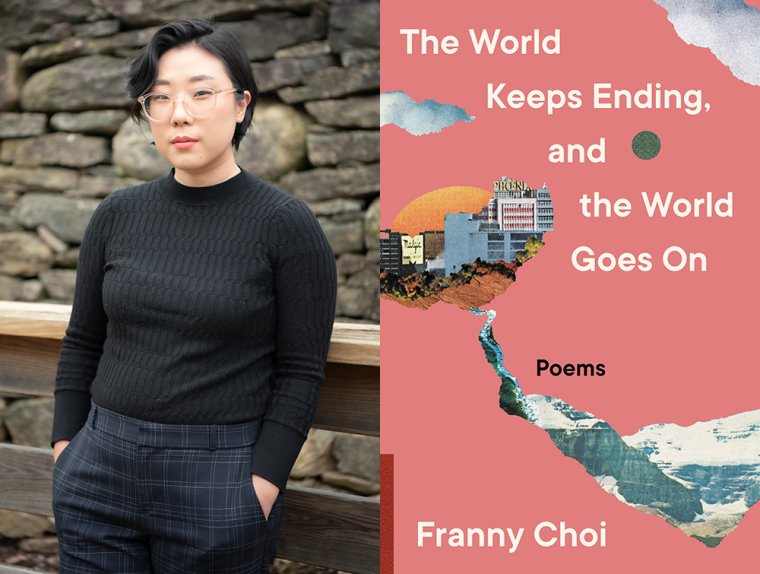

Franny Choi, author of The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On. (Credit: Francesca B. Marie)

1. How long did it take you to write The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On?

It’s sort of hard to say! I wrote some of these poems long before I understood what the project might be. The first version of the manuscript—which I threw together during a writing retreat organized by Hieu Minh Nguyen with a few friends in spring 2019—looks quite different from its final form. But I would say it’s about seven years in the making.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

By far the most challenging thing was trying to articulate the poetics of Asian American/Korean American solidarities with other liberation struggles, especially when it comes to frictions and other complicated entanglements. It is weedy territory, but my hope was to employ the spookier, subtler powers of poetry to help me navigate these questions. I’m also consistently surprised at how hard it is to write speculative poems, especially those that try to imagine something better—without getting unbearably corny!

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

It has been different for every project and period of my life! For a large part of this book’s process, I was working in pandemic time, so there were stretches when I was writing pretty much every day. But I would say that I average about one purely generative writing session per week; usually starting a piece late in the night and “finishing” it (i.e. starting the revision process) the next morning.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m in the middle of researching for my next project—an essay collection about race, gender, and robots in literature and visual media—so I’m partway through a novel, The Wind-Up Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi, and Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in Speculative History and Media, a book of academic essays edited by David S. Roh, Betsy Huang, and Greta A. Niu. I’ve also been flipping between a few books of creative nonfiction, including You Play the Girl: On Playboy Bunnies, Stepord Wives, Train Wrecks, & Other Mixed Messages by Carina Chocano and Writing to Save a Life: The Louis Till File by John Edgar Wideman.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I love thinking about how to build a narrative/emotional arc within a poetry collection. It’s somewhere between a novel (watching a character go through a journey of discovery and growth), a playlist (curating an emotional experience for the the reader/listener), and an essay (following a speaker as they grapple their way through an argument). I think the direction of the arc depends on the question that launches the book, which in this case was something like: What does one do with the knowledge that we are living at the end of a world? In the process of trying to ride out that question, I ended up moving from the apocalyptic present, to the apocalyptic past, to a series of unknowable futures, and then back, finally, to the present.

6. How did you arrive at the the title The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On for this collection?

That title comes from a conversation I had with my partner, Cameron, after the election in 2016, during a time when everyone I knew was talking about the end of the world. I was deep in the muck of despair when he said, “Well, maybe it’s helpful to remember that the apocalypse happened a long time ago, and that we—and our people—have been surviving it for centuries.” He was quoting some combination of Sun Ra (“It’s After the End of the World”) and Public Enemy (“Armageddon been in effect”), and many other Black and Indigenous thinkers who have long understood that all of us are making our lives in the aftermaths of great cataclysms. And it was helpful, somehow, to remember that; it made it seem a little more possible to face the so-called singularity of our times.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On?

The revision process for these poems was pretty different from my last project. Rather than tinkering away at drafts, I did more full rewrites, where I scrapped the whole poem and started again at the top. I think it has something to do with prioritizing musicality in a slightly different way, because I find that making little edits here and there can sometimes have the effect of clipping my rhythms. By contrast, starting over allows me to take the lessons I’ve learned in the last draft and move through it again, while staying in the time signature and leaving room for improvisation. Maybe, though, revising this way also has to do with being a little less precious, these days, about the drafts, and with understanding that in order to keep pushing my craft, I can’t afford to be afraid that any particular poem is the best one I’ll ever write.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The World Keeps Ending, and the World Goes On, what would you say?

The more you write, the more there will be to write about—so you’ve just gotta cut it off at some point!

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Listen to a lot of Democracy Now; read works of speculative fiction and poetry; go to protests in my town (or watch them from the window of our apartment); pace around anxiously; organize a retreat for poets and movement workers through a project I started called Brew & Forge; wallow at home; grieve with friends; teach a class on poetry of the apocalypse; have hard conversations with my family; read about Korean history; read Cesaire, Celan, Akhmatova, Neruda, Baraka; have a few bad days; talk to Cameron and my friends; apply for jobs; cry.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

“You only funky as your last cut.” —Andre 3000, often quoted by my friend, the poet Nate Marshall.