This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Jamel Brinkley, whose new story collection, Witness, is out today from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. This moving group of tales explores the experience and ethics of being an observer or bystander—in the drama of one’s own life, the lives of others, and unfolding history. Characters grapple with the choice to respond or act and face the consequences, good or bad, that lie on either side of that decision. Other times action seems an impossibility in the face of overwhelming events, as in the devastating “Comfort,” which follows the grief-stricken sister of a man who has been murdered by a New York City police officer as she struggles to move beyond her rage and sorrow. Kindness is a form of volition in these stories, providing moments of grace that often go unseen or unacknowledged but nonetheless hold the world together. Kirkus praises Witness: “Brinkley’s stories carry a rich veneer worthy of such exemplars of the form as Chekhov, Eudora Welty, Alice Munro, and James Alan McPherson. ... After just two collections, Brinkley may already be a grand master of the short story.” Jamel Brinkley is the author of A Lucky Man (Graywolf Press, 2018), which won the Ernest J. Gaines Award for Literary Excellence and was a finalist for the National Book Award, the John Leonard Prize, and the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. His work has appeared in the Paris Review, A Public Space, Ploughshares, and The Best American Short Stories. He was raised in the Bronx and Brooklyn and currently teaches at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

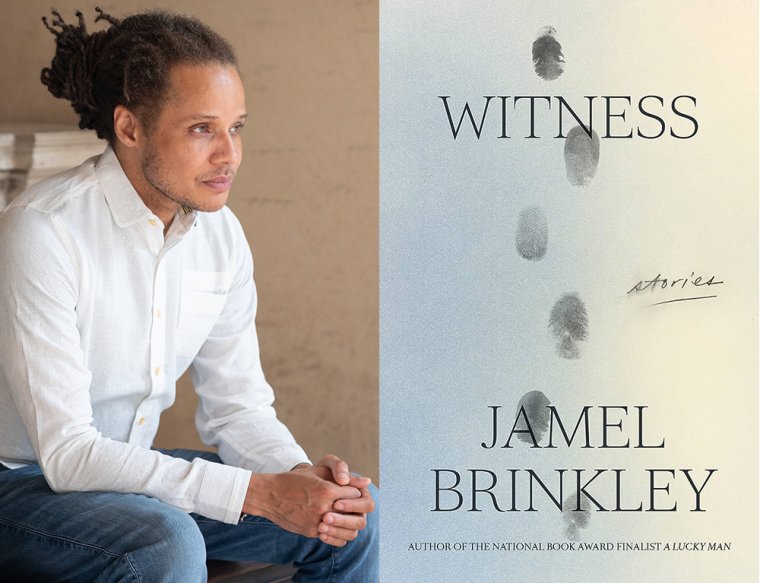

Jamel Brinkley, author of Witness. (Credit: Daniele Molajoli)

How long did it take you to write Witness?

Thanks to a fellowship at Stanford, it took me a little over four years, including revisions and edits, although the oldest story, “Arrows,” was first drafted back in 2013. The newest story, “That Particular Sunday,” snuck into the collection in early 2022, during the editorial process with Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The collection gathers characters who, in many cases, fail to perceive or fail to act. One challenge was to find ways around their perceptual limitations and deliver stories that were still vivid, sharp, true, and full of feeling. Another challenge was to make sure that any passive tendencies on the part of the characters didn’t cause the stories themselves to become inert.

Where, when, and how often do you write?

I tend to write at home, at my desk, and I hope to write for two to three hours in the morning at least four or five days a week. This summer I’ve been putting in some afternoon sessions as well. That frequency is only possible when I’m not teaching during the academic year, however.

What are you reading right now?

I seem to be perpetually rereading The Transit of Venus by Shirley Hazzard. I’m also rereading Angels by Denis Johnson as well as three books for a seminar I’m teaching this fall: King Lear, The Age of Innocence, and Song of Solomon. I just picked up Francisco by Alison Mills Newman and To the North by Elizabeth Bowen.

Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

For Witness, James Baldwin and Gina Berriault were crucial, as were Mavis Gallant and William Trevor. More generally, I also think a lot about Edward P. Jones and my teachers Yiyun Li, Marilynne Robinson, Lan Samantha Chang, and Charles D’Ambrosio.

Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

It depends. You certainly don’t need one to be a writer. Pursuing an MFA was the right move for me personally, and I had a positive experience. There are no perfect MFA programs, and if you sift through all the lazy nonsense out there, you’ll find some specific and valid critiques of them. But a good program that is the right match for you can supply time, an engaging community, a little bit of money, and a credential that perhaps can be useful. I wouldn’t recommend the experience to egoists. If you assume you are superior to other writers, are offended by the idea of being critiqued, or get a kick out of poisoning atmospheres, do not pursue!

What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Simply having consistent sources of intelligent encouragement, which both my agent and editor are, has been invaluable.

What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Witness?

One of the pleasures of writing short stories for me is the surprise of an ending. The moment when I realize how and where a story is going to land—when I hear that sound, its click of completion—is so delightful and sometimes chilling. In the process of writing a collection, I get to have that experience over and over again.

What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I had to do research on various topics, such as deed theft, and on various kinds of workers: people who drive delivery trucks, who work in hotels or in flower shops, who stage homes that are being sold, and so on. The research was interesting and pleasurable.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

I’ve gotten lots of good advice, but one piece I’ll mention is to embrace the problems that emerge as you’re writing. I think of these problems as puzzles that invite the response of the writer’s unique creativity and as portals that will eventually lead you to the work’s depth and complexity.