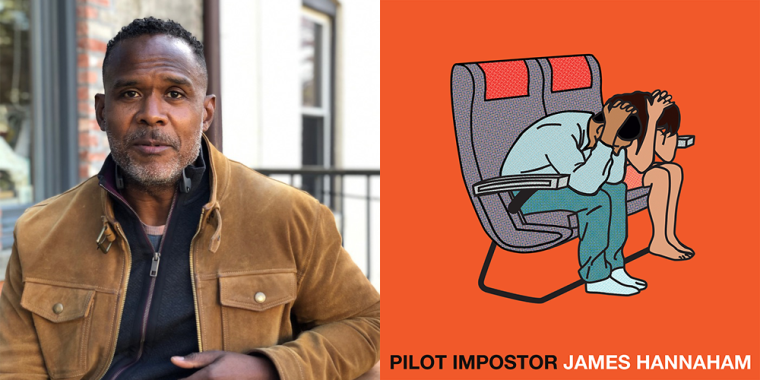

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features James Hannaham, whose latest book, Pilot Impostor, is out today from Soft Skull Press. Throughout Pilot Impostor, Hannaham wrestles with the potential futility of his own project—of making art in a time of (and about) disaster. He asks: “Doesn’t it lately seem a foregone conclusion that the psychotic combination of our science, our religion, and our stupidity would lead us to self-destruction? How much of a chance does this piece of writing have to last?” Yet he persists, despite despair, and strives to make sense of the most extreme catastrophes of the modern era, from isolated plane crashes to systemic racism. Inventive in form and told with devastating wit, Pilot Impostor reveals the volatility and perilous edges of human consciousness. “Pilot Impostor takes us on an exhilarating, incandescent ride,” writes Monique Truong. “Words crash, meanings disintegrate and reincarnate, histories disappear and appear on the radar, and against all odds the pilot knows exactly where we’re headed.” James Hannaham is a writer and visual artist. He is the author of the novels God Says No (McSweeney’s, 2009), which was a Lambda Literary Award finalist, and Delicious Foods (Little, Brown, 2016), which won the PEN/Faulkner Award and a Hurston/Wright Legacy Award. His writing has also appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Out, and 4Columns, among other publications.

James Hannaham, author of Pilot Impostor. (Credit: Isaac Fitzgerald)

1. How long did it take you to write Pilot Impostor?

The idea that it would be a book came to me on Sunday, December 18, 2016, while traveling from Nelson Mandela International Airport in Praia, Santiago, Cape Verde, to Lisbon, Portugal, on TAP Portugal Flight 1534, departing Praia (RAI) 13:40, arriving in Lisbon Humberto Delgado (LIS) at 18:45. I finished the writing part sometime in the spring of this year, maybe April, and getting photo permissions took until July? So almost exactly five years. But I was writing a novel at the same time, so maybe it would’ve taken me less time to write both if I had worked on one or the other.

2. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

I suppose it was the sudden, strong feeling that I could turn various obsessions into a book that I got after reading the first section of “The Keeper of Sheep,” the first poem in Fernando Pessoa & Co., an anthology of Fernando Pessoa’s work. Supposedly penned by the heteronym Alberto Caeiro, it begins, “I’ve never kept sheep / But it’s as if I did.” Caeiro is supposed to be a mystically nonmystic poet who espouses the idea that perception is everything, that things are exactly what they look like. This sounded sort of like totalitarianism to me, though I might not have said so in that moment.

3. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Getting—and paying for!—photo permissions after having grabbed so many random images off the web turned out to be pretty difficult. Which is proof to me that I wasn’t really thinking that I would get it published, I was just doing it to do it. I have a few other unfinished projects like this on my laptop going years back.

4. Where, when, and how often do you write?

It depends. I have an art/writing studio separate from my apartment, where I might do any number of things in a given day, round-robin style, usually in the mid-to-late afternoon. How often I write depends on what parameters. I like to include the thinking part of writing in the process, not just the sitting-in-front-of-the-laptop-and-bashing-the-keys part; thinking is really about 90 percent of the work. So I’m going to say I am always writing something, because I never know what material or experience will turn out to be significant to a project, and I’m “Always thinking / Always busy cooking up an angle / Working on the tiny blueprint of the angle / Sketching out the burning autumn leaves,” as They Might Be Giants once put it.

5. What are you reading right now?

My students and I just sort of finished The Bear Comes Home, which was polarizing, and so good fodder for discussion, and this week we’re reading Maus, which, it is a little embarrassing to say, I have known of for decades without having read it in its entirety.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

It would be easier to say which ones deserve less wide recognition. Over the summer I wrote a piece about William Gardner Smith and his book The Stone Face; I feel as if that guy didn’t get his due. I feel as if Earl Lovelace has been overshadowed by V. S. Naipaul—he is not alone, I know—which irritates me because Lovelace is far more compassionate and funky and his sentences are just better. Writing in translation generally does not get enough attention in the United States.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Pilot Impostor?

I started out thinking the book was about failures of leadership and incompetence masquerading as experience and then at a certain point it became a metaphor for living inside one’s own mind—that is to say, being the pilot of a doomed vehicle, not really knowing what was real and what was unreal, having questions about one’s own identity and those of others.

8. How did you know when the book was finished?

When we got done with the photo permissions.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

Clarinda Mac Low is always the first person to whom I show my work, because she has read really extensively, she reads really quickly, and she can gently describe to me what’s working and what’s not. She shares with me the inability to separate artistic community from family. She’s not at all associated with the publishing world—she’s much more of a dance/performance/art person, and that community was and remains foundational for me and my values.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Jennifer Egan once said to me, “You have to give yourself permission to write badly.” But then she also said, “The only leverage we have is the quality of our work.” These I think are the bookends of the process. I think of the first while drafting and the second while editing.