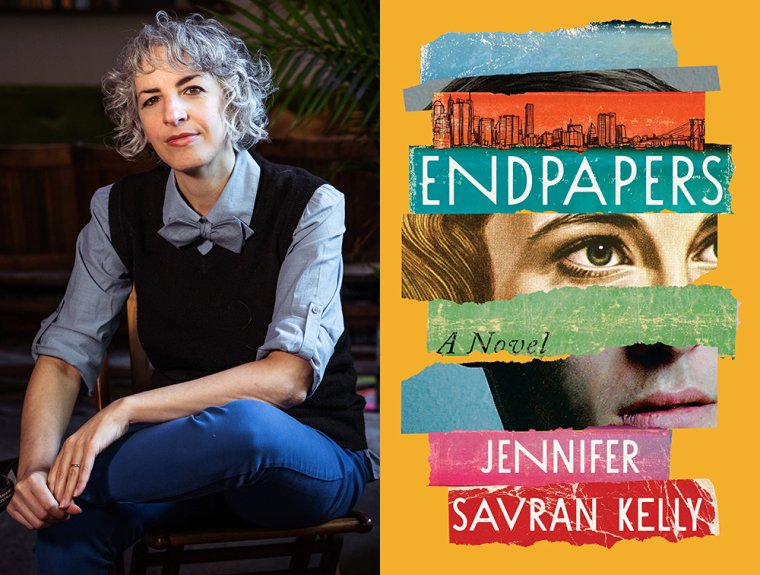

This week’s Ten Questions features Jennifer Savran Kelly, whose debut novel, Endpapers, is out now in paperback from Algonquin. In this literary mystery, Dawn, a book conservator at a New York City museum in the early aughts, finds herself in the midst of a life crisis, feeling perplexed about her gender, romantic relationship, and artistic career. Running out of time to prepare the work she is expected to show in an upcoming gallery exhibition, Dawn finds something that offers a clue to all three of her problems: a love letter written on one side of the cover of a 1950s lesbian novel, which had been torn off from the original book and stashed behind the endpapers of another. Compelled to find the letter writer, Dawn confronts a queer past that is even more oppressive than the present. This new historical knowledge inspires Dawn to take artistic action with a project challenging popular queer narratives in literature. Publishers Weekly praises Endpapers, calling it “richly imagined.... [I]t’s Dawn’s evolution as an artist and a person that gives the novel its beating heart. Readers will find lots to love.” Jennifer Savran Kelly is a bookbinder and production editor at Cornell University Press. A winner of a grant from the Barbara Deming Memorial Foundation, their work has appeared in Black Warrior Review, Hobart, Potomac Review, and elsewhere.

Jennifer Savran Kelly, author of Endpapers. (Credit: Darcy Rose)

1. How long did it take you to write Endpapers?

I had a vision for the story in 2014, but when I sat down at my computer, all that came out was one very long, winding sentence. I thought it was terrible, so I closed the document and didn’t open it again until two years later, when Trump was running for president and it looked like he might actually win. Suddenly, because the main themes of the book were gender fluidity and Judaism, I felt a greater sense of urgency to tell the story. I finished writing it in 2019, but after many more revisions with my agent and editor, I wrote the actual last word sometime in 2022.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I wanted to tell a story about different instances in history, both recent and further back, of oppression of the LGBTQ+ community and other marginalized groups. But I was afraid I would end up writing a treatise instead of a novel. As I researched the Holocaust, the Lavender Scare, and post-9/11 New York City, I paid careful attention to personal accounts of what it was like during those eras—and not only about events—so that I would be able to create characters who felt alive on the page, with personal motivations and desires. As interested as I am in these histories, I didn’t want to simply report on them. I don’t mean to diminish the important role of historians; as a fiction writer, however, I wanted to create a world in which readers could envision themselves. I hope I was able to achieve that to some extent!

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I have a small, antique desk next to a glass door in the corner of my living room. I wish I could say I write there, but more often I write cozied up on my couch, usually with one or both of my cats snuggled nearby. I work full time and have a teenage kid, so I do almost all my writing in the early hours of the morning before anyone else in my house wakes up and before my workday begins. Occasionally I find time to write on weekends, or I get away for weekend retreats when I need to make more progress on something.

4. What are you reading right now?

I have the honor of reading an advance reader’s copy of the book Cactus Country: A Boyhood Memoir by Zoë Bossiere, forthcoming from Abrams Press. I can’t wait until everyone gets the chance to read it! I’m also listening to an audiobook version of Jane Eyre, which somehow I’ve never read. I’m so happy I’ve finally made my way to it; the narrator is Anna Bentinck.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

In general, Marilynne Robinson, Jorge Luis Borges, and Miriam Toews. I first read Robinson’s Housekeeping in college, and everything about it—from the prose to the story—just floored me. If I’d dared to think of myself as a writer back then, that book would have inspired me to write a novel much earlier. Toews was a later, accidental find. I was taken by the cover of All My Puny Sorrows on a bookstore shelf, and I’m glad I trusted my instincts. It’s a great story, but I’m also really impressed with Toews’s craft. I never imagined I could laugh my way through a novel about someone’s sister wanting to commit suicide, but Toews finds many moments of humor in the grief.

While I wrote Endpapers, I reread James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room and discovered Alexander Chee’s Edinburgh. Though they’re very different books, the beautiful writing and the passion in both inspired me greatly. I also reread portions of Female Masculinity by Jack Halberstam, which I’d read in college. It was the first book that made me feel like I could begin to understand my feelings about my gender.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Endpapers?

Until I found a publishing home for Endpapers, a main subplot focused on the Holocaust. The editors at Algonquin liked the story, but they thought it would serve the novel better if I replaced the Holocaust storyline with one from a less-written-about time. My first reaction was resistance. I’d already done a lot of revising, and it meant changing about a third of the book. But their reasoning made sense to me. A subplot about a Holocaust survivor can’t help but overshadow a main plot about someone trying to come to terms with their gender in the early 2000s.

A brief internet search brought my attention to the Lavender Scare, which I hadn’t known much about. During the McCarthy era, the government sowed a moral panic about homosexuality, resulting in thousands of government employees losing their jobs. The tactics used to discover people’s sexuality were kept secret and trials were held in private. People who were accused of being homosexual or even associating with homosexuals were denied access to information about their own cases. When the Lavender Scare finally ended, after decades, many of the government files were destroyed.

In my research I also discovered that the invention of the queer pulp novel had overlapped with the Lavender Scare, allowing people in the LGBTQ+ community to both see themselves in literature for the first time and to find one another. Ultimately this allowed some groups to organize. Within twenty-four hours of learning about these two things, I couldn’t wait to revise Endpapers. The new setting also gave me an opportunity to tie the subplot deeper into the main plot, by drawing a meaningful bookbinding connection between the two characters.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

The first time I spoke with my agent, they said one of the things they liked best about Endpapers was that Dawn, the main character, is messy and human and not a model of queer perfection. I wrote Dawn as someone who’s weathered her fair share of difficulty and who has anxiety, but I have a lot of empathy for her, and it surprised me to learn along the way that some readers think she’s a real jerk. Although I can certainly see their point, I struggled because I didn’t want to sanitize her for the sake of making a likeable character, yet I wanted readers to sympathize with her, at least to some degree. My agent’s feedback gave me the courage to move ahead with a character who doesn’t depend on having a consistently kind demeanor to demonstrate that queer people—and all people everywhere—deserve dignity.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Endpapers, what would you say?

Believe in the process. Have patience and keep an open mind. Look for the agents and editors who share your vision for the work and trust them.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I did a fair amount of research—first on the Holocaust, then the Lavender Scare and queer pulp fiction. I also had to remind myself of the popular culture and headlines from 2003; it’s amazing how much has changed in twenty years, especially the technology.

Less tangibly, I had to do a lot of self-reflection because, like Dawn, I didn’t have language like “nonbinary” or “genderqueer” when I began writing the book. I’m pansexual, and I’ve pretty much always questioned my own gender and played around with androgyny, but I never knew what to call that, so I wasn’t confident I had a right to be telling this story. It forced me to face a lot of thoughts and feelings I’d tried to put aside many years ago.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

There have been two, and I can’t choose between them! One is for long-form writing: Keep going, and don’t look back until you get to the end. Make notes all you want, but don’t revise until you complete the first draft. I’m sure this doesn’t work for everyone, but it works for me—although I cheat from time to time when inspiration calls for it or when I know a revision will actually help me move forward. The second is to find a way to make your main character do the one thing they’re most afraid of or that goes against everything they’ve ever thought they would do.