This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Jordan Kisner, whose debut work of nonfiction, Thin Places: Essays From In Between, is out today from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Blending reportage with personal memoir, Kisner examines various uncanny scenes from modern America. She traces her own brief but intense foray into evangelical Christianity, the history of mental health treatment from exorcisms to pills to electrode therapy, the rise of the robocall, and more. Kisner exposes the rules human beings have enforced on one other in order to cope with their fear, mortality, and permeability. And with unique empathy and intelligence, she ponders how American communities and she herself might begin to question their orthodoxies and experience a new kind of vulnerability and faith. “With revelatory grace and insight, these essays refract the world you think you know in a new and brilliant light,” writes Alexandra Kleeman. Jordan Kisner writes criticism for the Atlantic. Her writing has also appeared in n+1, the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, and other publications. Her work has won a Pushcart Prize and been selected for The Best American Essays 2016. She lives in New York City.

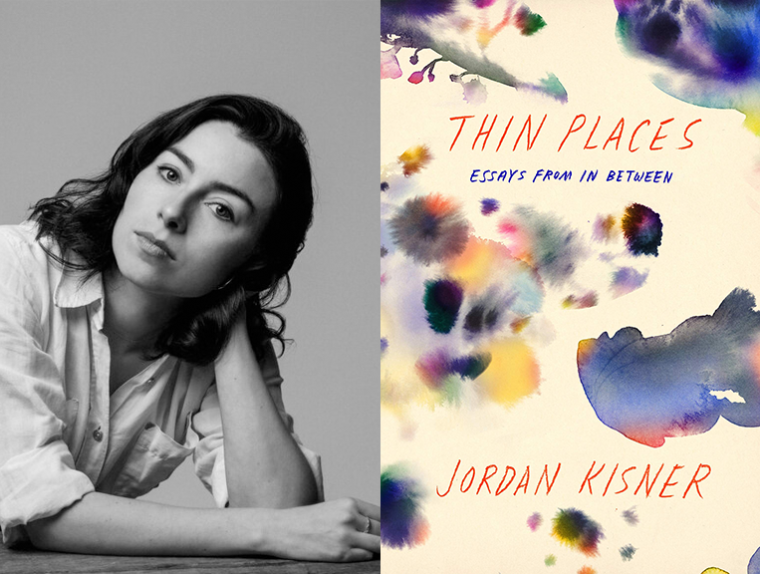

Jordan Kisner, author of Thin Places: Essay From In Between. (Credit: Ebru Yildiz)

1. How long did it take you to write Thin Places?

I wrote roughly half the essays in a slow, sporadic way between 2013 and 2017, and then I buckled down and wrote the rest between June 2018 and June 2019.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The first essay, “Attunement,” took all seven years to write. I lost track of how many drafts I went through, but it’s some appalling triple-digit number. Initially, I was trying to cram all the ideas of the book into that one piece—the collection exists only because I kept realizing, incrementally, that this or that thought in “Attunement” needed its own essay. Once I realized that “Attunement” was actually an introductory essay, the challenge became finding a way to lightly establish the curiosities, intellectual concerns, and themes of the book—i.e. to indicate a sense of intention in the essays that follow, which are fairly catholic in subject matter—without being ham-fisted. I’ve always admired Toni Morrison’s openings—in her novels, the whole book is somehow contained in the first few sentences, though on first reading they don’t seem freighted or microcosmic, just compelling. I wanted to do that here, which felt like a tall order.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I struggle with establishing any writing routine, though I thrive in the short periods when I manage to keep one. I write at home, in a small office in my apartment, and lately, I try to write three pages of notes or stream-of-consciousness babble at the start of the day. How much I write for the rest of the day depends on what deadlines are coming up—I only get things done because of deadlines, though I dread deadlines. At least half the time I’m working I’m reading, reporting, researching, or taking notes. When I draft, it’s often in big heaves—a few calamitous days rather than a measured, thoughtful approach. I think the measured approach would be better.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just reread The Folded Clock by Heidi Julavits, which I tend to pick up every few months and begin rereading from someplace in the middle. That book is friendly and intimate and so smart and—I mean this as the highest praise—refreshingly odd, and I prescribe it to myself when I’m feeling strung out or blue or like my brain is broken. It’s restorative. I’m also reading Homie by Danez Smith, which is so beautiful that it’s making me cry while I read, which I never do.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

She’s certainly recognized, but I’ve always wondered why Amy Fusselman isn’t wildly and extravagantly famous. Her books are so fearless, hilarious, brilliant. I keep extra copies of her memoir 8: All True: Unbelievable lying around so I can give them away.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Generally speaking, I avoid recommendations that prompt anyone to go into debt for any reason. That being said, lots of MFA programs don’t require you to go into debt, and I think studying writing at the graduate level can be useful under certain circumstances. I pursued an MFA because I’d spent all my school years intending to go into theater, and by the time I sorted out my real aspirations I was twenty-three and didn’t know where to begin. I desperately wanted to be initiated into the world of Literary Writerly Technique—as I then imagined it—and I wanted to study under writers I admired. I wanted their reading lists. I’m glad I went: I came out with a clearer understanding of the history and range of what you might call literary nonfiction, and with an idea of what I wanted to strive for. Also, I got the reading lists, and they were great.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Give yourself more leeway to think out loud on the page.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Thin Places, what would you say?

You’ll be fine.

9. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

The internet.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Read. Also: I don’t think this is good advice, or advice at all, but I once heard someone say, “A writer is someone who wrote today,” and I tell that to myself often. It’s not true—lots of writers don’t write every day; I certainly don’t—but often I find the notion of being “a writer” ephemeral and fraught, while being “someone who wrote today” feels straightforward and manageable. If you were to reframe this from a statement of (dubious) fact to a piece of encouragement, it would be nearly perfect: Just write today.