This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Juan Felipe Herrera, whose poetry collection Every Day We Get More Illegal is out today from City Lights Publishers. In Every Day We Get More Illegal, former U.S. poet laureate Herrera collects scenes and reflections from his travels across the nation. In one poem, the narrator is interviewed by a border machine; in another, an argument unfolds between the speaker and a nameless figure who claims, “you are a paid / protestor.” Excavating American institutions, Herrera forces a close examination of the roots of the nation—“a crust of war operations”—and begins to prepare the earth to heal. With hands firmly rooted in the soil, he reasserts the value of individual lives and stories, including his own. “First I had to learn. Over decades—to take care of myself,” he writes. Sweeping yet precise, Every Day We Get More Illegal is an intimate and urgent call to collective action. “In ways subtle and sometimes proudly loud, this book makes it clear exactly why Juan Felipe Herrera continues to be recognized and sought after for his work,” writes Jericho Brown. “You hold in your hands evidence of who we really are.” Juan Felipe Herrera served as the twenty-first U.S. poet laureate from 2015 to 2017. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he has published more than a dozen poetry collections in addition to short stories, young adult novels, and children’s literature. He lives in Fresno, California.

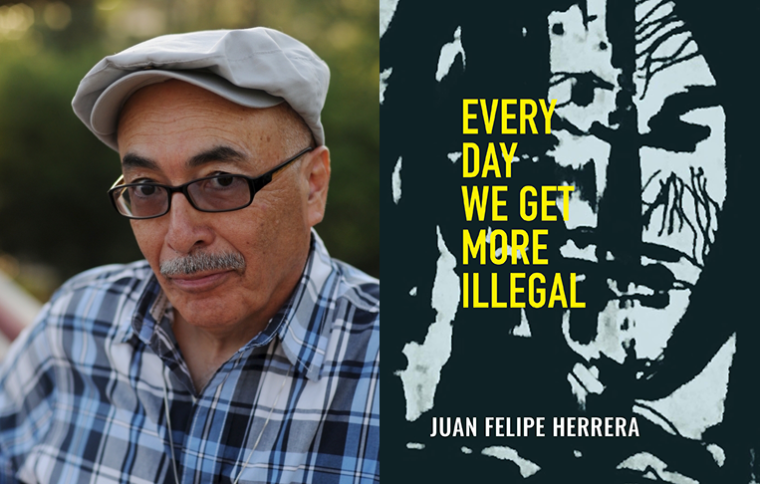

Juan Felipe Herrera, author of Everyday We Get More Illegal.

1. How long did it take you to write Every Day We Get More Illegal?

A year and a half. Briars and brambles—it contained cartoons, an excerpt from a new young adult novel draft, and many of the poems in this new book. Filtering out dry branches and thorny sketches and strengthening the remaining pieces with new work was the task. I was used to creating a collection in no more than three months. This new work was a grinning rebel—pounded its fists on the desk and stomped its feet calling for more depth and interrelationships within the flow of the poems. My editor at City Lights, Elaine Katzenberger, liked the original and also cut about forty pages. Mostly the cartoon section—what can you do? There comes a time when you realize that there is much more work ahead on a project you thought was complete. Elaine was meticulous—certain terms were questioned, lines and chapter arrangements were discussed. Back to the infamous chalkboard. I pulled back and noticed she was right at every turn. We worked together and there it was. Letting go and finding new routes and allowing the poem more space and more momentum was key. The cartoons, well, next time—on a parallel table.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The time the book required. Allowing insights regarding the work and particular poems to expand and mature was key, most important when you are used to a sizzling pace. Waiting while not stopping was the way of this book. It kept speaking; some lines were tinny, and I had to wait for the right word, just one term. It took months then blam! Other poems looked a bit dusty and not as tuned as the others. Not a big issue. They were comfortable. I left it at that. There are so many layers and voices within the voices and energy tributaries that flow across the book. As long as the circulation of words, lines, stanzas, speaking, force, and depth are moving through the entire system of the book, good. One of the most important aspects is the depth. This collection called for multilayer poems.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

As often as possible, daily. On whatever material is on hand. Eighteen by twenty-four newsprint is most liberating these days. Two desks, one of old wood from an antique store here in Fresno, California. The other, from a used sundry story in Redlands. Of course, Tombow pens, fountain pens, kindergarten green pencils, soft lead, Japanese quill pens, and India ink, photos, ceramic figurines, little karate kids, bills to pay, and an incredible scribbled sheet that claims it is my calendar facing tiny trees by the street. Daily energy is a key ingredient. At the 1985 Bisbee Poetry Festival, John Ashbery mentioned the he wrote once a week. When the poem throttles your innards, that’s when you got to hit the paper and arpeggio the keys—it’s up to you.

4. What are you reading right now?

Orientalism by Edward W. Said, a book of the late seventies that still provides templates useful in these times. Critiques of power and culture are most relevant in examining notions of how descriptions, narratives, and summaries of our identities and ethnicities are central to our social being and senses of humanity. The other book is Purity and Danger by anthropologist Mary Douglas, a book from the sixties. It is related to the ol’ cultural views of “pollution.” That is to say, who is “dirty,” versus who is “clean” and “pure.” Think about our ideas regarding nation, race, color, identity, borders, genders, sexual orientations—cultural, social, and political assignations are some of the most violently contested conditions facing us today. As writers and thinkers, it is most beneficial to have various ways to analyze our human predicaments. Poetry does this and it can be fortified as well. The deeper the lens, the better our discoveries and more incisive our views and language.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Every author. Poets abound. Every high school seems to have a poetry club and stage-ready mic. We need to promote the new generations, in particular women, trans, and LGBTQ+ poets. Expanding our notions of the definition of “poetry” beyond its institutions is also relevant—Raymond Williams, pioneer of cultural studies, discusses this in his investigations regarding the influence of power in literature, authorship, and the institutions of genre. Marvin Bell, one of my professors, always said before and during his readings at Prairie Lights in Iowa City, “No one knows what poetry is.” I love all of my poetry professors and mentors. They inspired my joy of writing, thinking, and being a poet. Back to the point: We do not have to respect the divisions of human “progress” that differentiates “savages” from “barbarians” onto the “civilized,” a caste-like social segment marked by its development of “literary products,” as Henry Lewis Morgan (“The Father of Anthropology”) wrote in his book Ancient Society in 1877. We are all authors. Let us acknowledge everyone.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Writing. Writing is more than writing. It is more akin to what Lu Chi, the great Chinese poet and literary critic of the third century, called a “delight” in his essay on the “Five Delights of Literature.” What drew me in was the “delight” of “tasking the void.” It took a while for me to unravel this joy. At one of my readings in L.A., I asked the members of a local high school poetry club the question: “What does Lu Chi mean by ‘tasking the void’?” A teen twisted his body and flapped one arm toward the walls as if throwing a discus. “That’s what it means,” he said. An appropriate Taoist response. “Ahhhh, yes! Moving the universe!” The “impediment,” then, is to be unaware of your “task.” That is, when your writing is “just writing” devoid of its quantum relationships with the ever-changing flows in the “audience,” society, and all things. At the ground-level, the need not to write gets in my way. There is more going on than “talking to yourself while you are putting words on paper,” my worried mother told me in a shivery voice decades ago in my Mission District apartment on Capp Street in San Francisco.

7. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

It’s already changing. The mega-wave of magnificent works by Latina writers and writers of color has encouraged an increased attention of publishers and the scope, story, and text of the book. In 1992, Roberto Trujillo, one of the head archival librarians at Stanford University’s Latin American, Iberian, and Chicano Collections, wrote in the San Francisco Examiner that in the past hundred years there had been about one thousand novels by Latinx writers, some of them “Chicanesque” authors, that is, Chicano-like texts. Today, that is no longer the case. The volume of Latinx novels expands daily. On the other hand, just maybe publishers could have direct lines to MFA programs and multicultural community centers throughout the nation and merge works with Latin America and the Caribbean—a more global body that needs a dynamic, collective forum. The entry into multilingual texts is also another opening publishers are welcoming. The time is right.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Every Day We Get More Illegal, what would you say?

You are doing great, Juan Felipe. Keep it up. I really like your writing while you are walking bit. And those yellow, legal-size paper pads are hilarious. And those red ink Schaeffer fountain pens, make sure you have the right side up in your white shirt pocket. Last time, when you were shopping for Susan Sontag books at the University Bookstore in Seattle, you literally painted your shirt crimson. Jeez. By the way, maybe you should take a poetry class once in a while—deeper sources, more possibilities. You’ve taken German literature in translation, Buddhism, printmaking. Focus, Juan. They got everything at UCLA, I know, but, come on! I like your writing—just organize it, okay? Get a folder! Good seeing you again.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

Bad habit, good habit: I rarely share it. An ancient pattern of mine. Sometimes I share some of the poems with my wife, Margarita. She is incredible and keen. Sometimes a poem or two, with one of my grad Laureate Lab poets, Anthony Cody, for example, or a good chunk of the text with the rest of the lab team. They are luminaries. I trust them all equally. My children’s book agent, Kendra Marcus, is magnificent, and my editor at City Lights, Elaine Katzenberger, does not hold back. The outcome: serious, unexpected evolution.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

“Hay que saber luchar!” My mother would always say this, “You have to know how to struggle, fight, survive!” She made it through the Mexican Revolution and its aftermath, all the way through the migrant farm working fields to San Francisco. Remember it is art. If you are not enjoying jotting words on scraps of paper, tapping Jazz-like onto the keyboard, noticing tiny realities appear out of the blank universe, the breath of it all, the bounce into the world, the odd-angled something talking, the various stops, pauses, silences, emergence moments, revelations, the gripes, the stubborn figure you’ve become, the ecstatic face you generate when you are “done,” the funky cohort you apparently have joined as you continue, the voices you throw out when you read your work, the variety of printed-out sheet stacks on your desk, this odd plankton you have become swishing toward the oily surface of brilliance at the very top edge of the murky waters, then maybe you got to loosen up or move on to fiction or a “real job.” How about painting?