This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kendra Atleework, whose debut memoir, Miracle Country, is out today from Algonquin Books. Miracle Country begins in 2015 as a wildfire devours Atleework’s hometown, Swall Meadows, an obscure outpost just east of the towering Sierra Nevada mountain range. While the region had always been prone to extreme weather—fires, floods, blizzards—this fire was unique for arriving in February, when snow cover would usually offer some protection. Beginning with ash, Atleework moves back and forth in time to tell the story of her complicated relationship to this landscape that’s become increasingly volatile due to climate change. She remembers how her parents taught her to love and thrive in the desert, but how this love became strained after the loss of her mother to a rare autoimmune disorder. No matter where else she travels, however, Atleework writes, “I am always thinking of home.” A narrative of both flight and return, Miracle Country is a love letter to family, home, and the earth. “Blending family memoir and environmental history, Kendra Atleework conveys a fundamental truth: The places in which we live, live on—sometimes painfully—in us,” writes Julie Schumacher. “This is a powerful, beautiful, and urgently important book.” Kendra Atleework is a graduate of the MFA program at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Her essay “Charade,” which became the basis for a chapter in Miracle Country, appeared in The Best American Essays 2015. She serves on the board of the Ellen Meloy Fund for Desert Writers, and lives in Bishop, California.

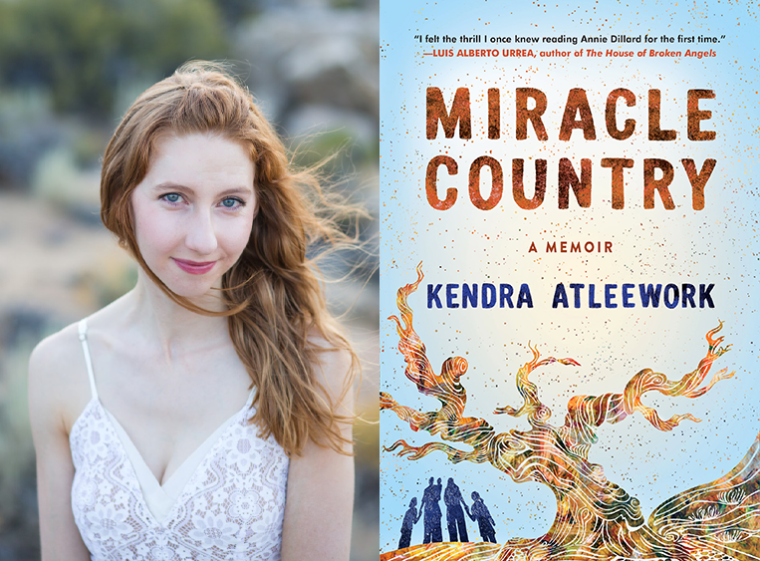

Kendra Atleework, author of Miracle Country. (Credit: Amy Leist)

1. How long did it take you to write Miracle Country?

I worked on the book for a solid six years, but the idea began with an essay I wrote in college called “Charade”—the assignment was to write about grief, and so I wrote about what it was like to be a high schooler living on a mountainside and losing my mother. Research and years of studying craft allowed me to refine that kernel into a book.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Creating a structure. It took years of revision to find Miracle Country’s narrative spine. It was never going to work as a more traditional, chronological memoir—even though I rewrote an entire draft that way! I had to wrangle a narrative arc out of centuries of history, mounds of research, the fraught lives of my own family members, and the most emotionally loaded pieces of my own life. That was a challenge.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Reading and researching are, for me, inseparable from the writing process. I grab every chunk of the day that I can to read. I sit on the floor with a book strapped into my nerdy bookstand and I read while I eat breakfast, again while I eat lunch, and so on. As for writing, I often draft the messy new stuff late into the night.

4. What are you reading right now?

In West Mills by De’Shawn Charles Winslow, which just came out in a beautiful paperback edition. I love stories about small town life, and this novel gives the reader a glimpse of rural North Carolina, where a canal marks the color line. It’s a family story with characters that vivify their homeplace. And the writing is lovely.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Ellen Meloy. I’m always surprised when readers of nature writing and the literature of the West haven’t heard of her. Meloy transcends genre. Her voice is quirky and warm and her prose is stunning. In one essay from her book The Anthropology of Turquoise, a home repair project turns into a thought experiment when she accidentally staples her hair to the roof. I also appreciate her revolutionary celebration of things devalued by capitalism: beauty in its many manifestations, and the desert, despite its apparent infertility and lack of resources to remove.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Social media! I’m excited to connect with readers there, I like sharing about other authors’ work, and it’s certainly led me to discover a lot of cool books. But I’d prefer to be walking with the local cows on the canals than doing anything on my phone.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Patience. My wonderful agent, Janet Silver, taught me this through her unwillingness to rush this book, and I am so grateful. Could we have gone out years earlier and sold the book? Perhaps. But giving it time to develop allowed it to become something I’m extremely proud of. It was a lengthy process with a lot of tossed pages, but nothing is wasted when it comes to writing—a finished book is the tip of an iceberg of invisible work. Janet’s willingness to read draft after draft, and to ask me hard questions, allowed Miracle Country to grow into itself.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Miracle Country, what would you say?

I wouldn’t tell her anything! Let her learn the hard way! I especially wouldn’t tell her that she’ll wind up working as a snow shoveler in Minneapolis to fund her writing habit. Otherwise she might sabotage me by, like, getting a desk job.

9. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

It’s clear that all industries need to purge themselves of institutional biases, systemic racism, existing in thrall to capitalism, etcetera. Easier said than done. As a way toward achieving that goal, I would love to see the essay gain greater recognition as a literary genre. I would love to see it represented in popular culture as robustly as the novel. What I love about the essay is that it deals in uncertainty. The questions an essayist poses are not answered, or even answerable—instead, over the course of the writing and thinking, they become more complex. Amping up our tolerance of complexity and nuance could save us from the devils of our own nature, I believe: our tendency to be reactionary, to entrench, to not listen. We need the sensibility of the essay to rescue discourse.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

In the early stage of a project, write fragments. Don’t get bogged down by trying to conceive of the whole. My mentor in grad school, Patricia Hampl, taught me this during my very first semester, when I was convinced I would write the first page of my book, well, first. That’s a really absurd and funny idea to me now. Describe a photograph, she told me. Describe your father’s hands. Don’t worry for now about how it will all come together. Develop your instincts by reading—then trust those instincts. Feel for the thread. Follow it through the dark.