This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Khadija Abdalla Bajaber, whose debut novel, The House of Rust, is out today from Graywolf Press. Aisha’s father is known to be a skillful, if foolhardy, fisherman: “a master of the waves.” But then one day he doesn’t make it home. When no one is willing to venture out to search for him, Aisha, urged on by a talking cat, decides to go herself. Set in Mombasa, Kenya, The House of Rust is a gripping coming-of-age novel that features many surreal creatures and fabulist elements. Aisha’s rescue mission turns out to be only the beginning of a much wider adventure. “Khadija Abdalla Bajaber’s command of language and story is transcendent,” writes Wayétu Moore. “The House of Rust is an immersive experience in Kenyan mythology, and an honest exploration of loss and family from a uniquely talented writer.” Khadija Abdalla Bajaber is a Mombasarian writer of Hadhrami descent and the winner of the inaugural Graywolf Press African Fiction Prize. Her work has appeared in Enkare Review, Lolwe, and Down River Road, among other publications. She lives in Mombasa, Kenya.

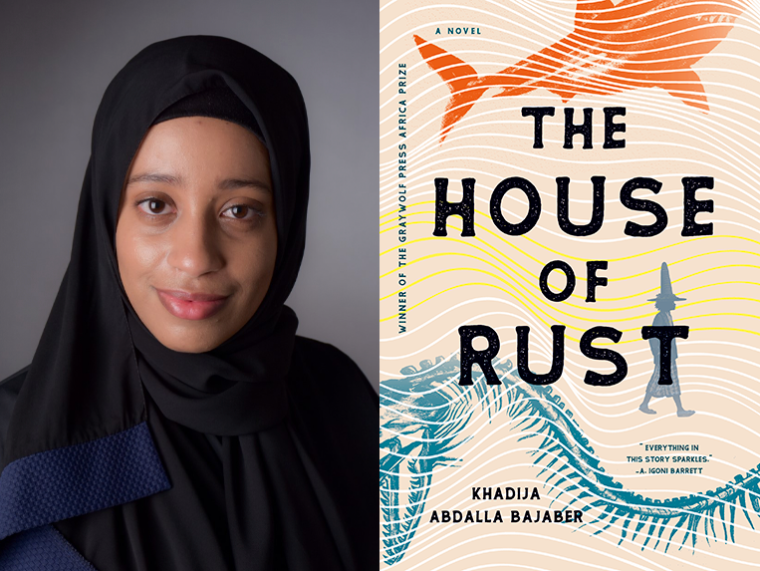

Khadija Abdalla Bajaber, author of The House of Rust.

1. How long did it take you to write The House of Rust?

My hard drive says…I typed some in early 2015. Submittable says I submitted it October 2017. E-mails say I started adding more in 2019 to make sure everything was resolved. So roughly three years, then that extra year on top. No less than three, no more than four. I don’t know what I’ve said in other places but yes. That’s more than I expected. This is the first time I’m seriously calculating it.

2. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

Lying on the floor, writing the first chapter, and sweating because of the weather. It was a new relationship and I said I’d commit myself. I put all my other projects aside, like physically stuffed all my works-in-progress into a box so they could not tempt me. I was writing the first chapter, which came together perfectly and ended so neatly that I paused and felt the doubt sink in, that it was all too neat, neat enough for me to end everything there and not stay committed to finishing it. I knew myself too well.

Wrote it, typed it, set in stone as if I was likely not going to come back to it.

Because of a power cut, my mom asking me for a story in that airless dark, hot, unbearable sitting room where we all gathered—because I already had a beginning, and she asked for a story I was able to tell in one sitting. So basically the story was spoken, then written. If it wasn’t for that, I’d probably never have completed my story because I didn’t believe I could complete it. There’s my blessed mother, letting me spin and make things up on the spot—three-act structure, primary protagonist, inciting incident—all of it just came so quickly. So I had the story. Told like a fairytale.

I didn’t tell them I was writing it before, or that I was going to write it. I didn’t want to shadow everything with writing anymore. I just wanted to have the simple pleasure of being a storyteller. I’m not particularly charismatic or entertaining enough to spin the yarn out loud, but that night unlocked me.

From despondent on the floor to free in the dark—moving from doubt to faith—Mama and my family there during the power failures…that was the moment that got everything to happen for me.

3. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I added more to the book as we were editing, which meant writing chaotically and without rules. Then darlings were killed. I wouldn’t say it was hard, but it took some careful thought to figure out how to arrange everything together so that it read just right. Moving new scenes about, working in new information in old scenes, writing and editing at the same time. Big puzzle. But Alhamdulillah, with the guidance I had from my editor, Steve Woodward, his encouragement and his attention to detail, the book got to where it needed to be. I did have to physically leave home and cross a border in order to get this work done—Mombasa at that time was just too distracting. But once I got that distance and that time, matched with not holding back and aided by the advice and guidance of a stellar editor, things worked out well. I kind of wished all my other projects were as obedient. The only really hard thing is what sticks to you long after the work. You’re steeped in the soup of one book for so long it’s hard to move on creatively to something new. I love The House of Rust, but I’ve been in there for so long that it’s been difficult giving myself over to new work as completely.

4. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Tried to do the writing desk thing—all my implements are there. Sometimes it really works, sometimes it doesn’t. Lying on my bedroom floor or lounging about with a pen and my beat-up book works best: I rest my cheek on the floor when I’m winded or when the cats start pestering me climbing over everything. I do more poetry on the table in my room or in the shared sitting area of the house whenever I feel stifled. I have tried to make a habit but the truth is I need to be enamored deeply with an idea to pursue it deeply, and when I pursue it deeply I disappear out of life and into the idea. Like a fever it runs its course until I hit a wall or life interferes with me for thinking I could leave it hanging. I never write when I’m angry; it gives me my best work but also my most brutally exacting.

Time here doesn’t just belong to me, I’m in Mombasa. You make time where and when and however you can, you adapt. I tried writing while everyone’s asleep, but that just makes me lose sleep. In an ideal world I’d be loyal enough to the craft to commit my hours more seriously, to hang the “Do Not Disturb” sign on the door—and have it respected, ha!—as I pace and chew literature and create fine things. But I need to live. I’ve learned now I can only match myself to the things happening around me. I need to be involved with life, its business, its noise. They are not interferences, they are color. Otherwise I just get swallowed up in my own bubble, echo chamber, self-same noise. When I write I keep my tools few; I need to be prepared to put them away, or swiftly move to another location in the house, because a cat is a jealous animal—they will sit on everything, they will follow you everywhere—you need to adapt. Writing lets me live, but I cannot let it be my life.

5. What are you reading right now?

The Making of a Story by Alice LaPlante. I also picked up Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón, but I’ve not got the attention or the stamina for a novel, so despite it being quite good and to my tastes, I’ve not made it very far.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I struggle answering this. I feel as though things are changing, wider recognition means better bank perhaps, it means better opportunities in the future but…it’s not enough anymore. We read our writers and write for our readers here on the home ground. No one is waiting anymore, they’re creating their own spaces. If it appeals widely or abroad, that’s not bad, but that’s not the be-all and end-all of it all anymore! It’s not enough! You sit around pining for this coy and miserly brat, you’ll be bones. It’s hard to get it, it’s a combination of factors beyond our control—and even if it’s gotten, can it be sustained? Commercially it’s good, it pays, but we can’t wait for it or chase it anymore. African literary organizations, African readers, African writers, are doing the work. Wider recognition is valuable, but this can never be more precious to me than seeing Kenyans read Kenyans.

Anyway I live under a rock so there’s no way for me to objectively know who is receiving the correct amount of wider recognition. I’ll shamelessly use this as a soapbox moment to highlight writers who write well in my opinion, regardless of whether they’ve written novels or not, or whether they’re recognized widely or not, because I told you I don’t know. The last novel I read and would like to recommend is T. J. Benson’s The Madhouse—moving, deeply beautiful, had me in tears. I’ll tell you what else I enjoy, what I’d recommend to a friend who has tastes similar to myself: Personally I enjoy reading Kenyan short story writers and African writers, poetry, fiction, nonfiction. Alexis Teyie, Michelle K. Angwenyi, Makena Onjerika, Gladwell Pamba, Kiko Enjani, Lorna Likiza, Shingai Njeri Kagunda, Rumona Apiyo, Troy Onyango, Linda Musita, Idza Luhumyo, and many, many more. Also literary magazines like Down River Road, Lolwe, Isele Magazine, Doek—these African publications are earning global attention though I don’t know if that’s something they were intending on doing, so much as a by-product of doing the work that’s most needed. But take a look through. Everyone in those is brilliant.

7. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

If I speak…right now I think I’m done. There are people who have the clarity, the focus, and feel strongly enough to articulate these things. When I feel too strongly, I’m afire, I can’t construct sense, it scatters me. I’m making the decision to focus on my work now. I can only take community in small doses. Besides, I’m a Kenyan, realistically the community I care about is the Kenyan and African community. The wider, global industry or community isn’t currently my concern—publishing, writing, industry, etcetera. When one cares for you so little, can you be judged that you think of them even less? Let me not have grand conversations, let me look home, after all that’s where the heart is. Even then I am mindful of how I involve myself. We’ve got our own communities here, with its strides and its challenges, so of course I’ll show up to support fellow writers in whichever ways I can, but these big broad conversations right now encompassing multiple borders, let the talk be had by those best suited to its postures. I am shamelessly deciding to concentrate on my own work.

8. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

Steve Woodward was my editor on this. I don’t think I could have had a better experience. I really relied on him, and when I added more to the book, he just let me go and do whatever crazy stuff I wanted! Of course later many darlings were killed, but it was really easy to do it. This is why I say there wasn’t anything actually terribly hard about writing the book. He made it all too easy, often all I needed was some time and a little energy. Steve gave me plenty of constructive notes and lots of advice was in them—like finding what the backbone of the structure of the book was, using what’s already available, building the story pieces around that. There are a hundred e-mails, all of them gold. I can’t think about exact advice that jumps to mind as clearly and neatly as this question requires, so much as the constant support I got there. This book would look very different without him.

Igoni Barret was also really great to talk to, someone whose insight I could rely on and who I could e-mail for advice about things every now and then—that’s grounded me. I’m really grateful for that as well.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I rarely share my work, but when I shared this book, it was with my close family: my parents and my siblings and their partners. My siblings were the first to read the completed draft. They loved it, when will that stop shocking me? Mama and Baba were slower—I think it’s difficult for them to read on a screen, they prefer the physical books—but they sat with their pens reading the final physical copy of the book, hunting for anything they know I’d regret leaving in or regret not going into correctly. Of course they’re able to spot lots of things I and the Graywolf team didn’t catch, because they’ve got inside knowledge of this world, right? They’re old Mombasa, they’re wiser. It helped a lot. With family I could feel confident. I knew I could trust them to get excited about the things I get excited about, and worry about the things I worry about, so they’ve been astute and a great comfort. And Steve Woodward, of course, who’s been here since the journey started.

As for work that wasn’t book-related but shorter fiction pieces, I was lucky enough to sign up for virtual fiction classes with Makena Onjerika at the Nairobi Writing Academy. I learned more from that than I ever could have learned writing quietly by myself. Every time I’ve gotten feedback from her it’s like a precious key, it unlocks. She may not know it—she’ll know it now if she reads this—but she’s my only reader who’s a writer. I greatly admire how wonderfully she writes—she’s the reason I’m on this arduous journey to master the short story.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

For this project I wish I’d read Chris Baty’s “Elephant Technique” a little earlier. It is invaluable, stops you from stalling. Whenever I begin to wonder and wander, hesitate on how to go about a thing or can see something is gonna slow me down I’d just write ELEPHANT and move on, that way I could come back to it later when I was done and only then.

So I used this while telling the story in a linear way, no skipping ahead to write scenes that we haven’t arrived at yet. You keep using the “Elephant Technique” for long enough, you don’t have to worry about abandoning the work anymore—because you’ve been using your instincts, writing reflexively, spilling it all. At the end the work isn’t finished yet, but it’s got enough life and spirit, your characters are living breathing talking, the mood has been set, things are unfurling, it’s alive. The worst has been gone through, now you’re amazed at how far you’ve come, you want to see how much further you can go. This method is good for those of us who are prone to distraction, but it’s not something I’m realistically able to rely on forever because I think I’m interested in pauses now. The writing I want to do now aims to be more thoughtful. I want it to ruminate more instead of rushing to finish a first draft, but it’s astounding how well it works once you just try it. It was mad how well it worked. Not a creative block it won’t bulldoze you through.

Recently, Daniel José Older’s advice about writing beginning with forgiveness—I can’t believe I needed that spelled out for me. But that was important to understand.

Okay, not advice, but a revelation…Makena Onjerika, who taught us—I was listening to an interview with her on Facebook Live and I typed this question: “What do you say to people who believe they can’t be writers?” or something along those lines, because I was tired of telling people that they too could be writers. And there I was sitting expecting some upbeat, optimistic, encouraging reply, some advice, something I could repeat whenever people were being weird about how oh they could never be writers! And she straight up says, “Writing is hard.”

I’m paraphrasing, poor memory and all. She says something along the lines of writing takes a lot of work, you have to be committed, it takes a lot out of you. It’s not for everyone, or not everyone can sustain it. Or something along those lines. And it blew my mind, because here I’d been like anyone can be a writer—but the truth is that I’ve been really struggling! She was right! I guess I was just so used to thinking of the work I do as interesting but indulgent perhaps, and I’d been seeing writing as just this way to express myself, but it’s not easy to express myself! I’d been miserable trying to figure this writing thing out! It’s not for the faint of heart, you’ve got to be purposeful if you commit yourself to it and hell is it a commitment.

I already respected Onjerika a lot, but that answer just skyrocketed my respect for her even further. How was she saying things I’d never even realized were true. That frankness, it made me start looking at my relationship with writing in a different way. Because I was having a hard time and feeling lousy about it, because it was supposed to be easy and good and simple, right? If I was talented, if I was meant to be a writing writer, wasn’t it supposed to just flow through me like some kind of spirit? But I’d be sweating, I’d be struggling, and I’d doubt myself because I know writing isn’t 100 percent easy, but I was sure back then that it wasn’t supposed to be the Herculean task I was having of it, I used to think I was failing for struggling. But Writing Is Hard, and realizing that it was hard, being told that yeah, writing is tough, it’s difficult. I needed to hear that.