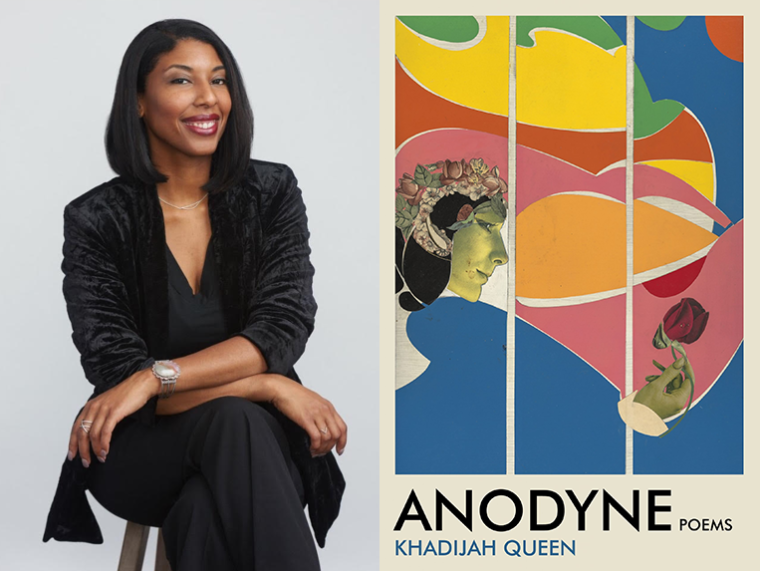

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Khadijah Queen, whose latest poetry collection, Anodyne, is out today from Tin House Books. Anodyne is a salve for disaster, in which Queen makes room for joy without denying grief. The first poem, “In the event of an apocalypse, be ready to die,” begins, “But do also remember galleries, gardens / herbaria.” In the second poem, Queen reflects on a loved one’s battle with depression, but also how she can make him laugh, how she’ll fight for him: “I would move the fucking universe for you,” she says. Meditating on family, history, landscape, and many other subjects, Queen always summons a diverse chorus of emotions and forms. In the darkest hour, there is always a “but”—always a capacity for transformation. “This is a powerful and dazzling collection, filled with wisdom and experience,” writes Ilya Kaminsky. “Anyone who reads Anodyne will remember it for a long time.” Khadijah Queen is also the author of Conduit, Black Peculiar, Fearful Beloved, Non-Sequitur, and I’m So Fine: A List of Famous Men & What I Had On. Her writing has appeared in Poetry, Fence, Tin House, and American Poetry Review, among other publications. Holding a PhD in English from the University of Denver and an MFA from Antioch University, she teaches creative writing at the University of Colorado in Boulder and in the Mile-High MFA at Regis University.

Khadijah Queen, author of Anodyne. (Credit: Michael Teak)

1. How long did it take you to write Anodyne?

From the time I decided it was a manuscript through to completion, about two years. But the poems range in age—some were first composed a couple of years ago, most between 2016 and 2019, and a few more than a decade ago.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I wrote much of it in the year after the 2016 election, so the most challenging thing was, and continues to be, living through the difficult sociopolitical circumstances we find ourselves in as a nation. I also felt torn at times between making the more fragmented poems narrative and letting them breathe how they wanted to. I chose the latter.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I have had different habits over the years. One thing I did during the process of writing this book is allow my writing practice to change with my abilities and responsibilities. I used to write every day—I did that for six years straight until 2015, when I had emergency surgery and had to recover. Now I tend to write in concentrated periods of time. That varies—weekends, a week, several weeks—depending on the project and what life has in store.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just taught Toni Morrison’s Sula and A Mercy, so those are still sitting very close to me. I am about to teach Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time, so I’m just starting to reread that. On my e-reader: Stephen Graham Jones’s The Only Good Indians, John Freeman’s The Park, Henri Cole’s Orphic Paris. On their way to me: Erika T. Wurth’s You Who Enter Here, Nate Marshall’s Finna, Elisa Gabbert’s The Unreality of Memory, francine j. harris’s here is the sweet hand, Maaza Mengiste’s The Shadow King, and Monika Sok’s A Nail the Evening Hangs On.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Ruth Ellen Kocher. Divya Victor. Karenne Wood. Yona Harvey. Simone White. Kate Durbin. Ashaki M. Jackson. Bettina Judd. Sarah Gambito. I could go on—so much brilliant work continuing to be made.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

I try not to think in those terms. Life has endless complications, obstacles, responsibilities, difficulties. Over the twenty years I’ve been writing poetry, I’ve tried to use them all in the work, even if I don’t get to the actual writing part until later. I think about what happens in life as part of the writing process, because it is—writing is part of my life, and life is part of my writing.

7. What trait do you most value in your editor (or agent)?

I value honesty most.

8. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I think everyone has to make that choice for themselves. I value my MFA and I do think it was worth it. I wanted professional training and I got it. I wanted a community of writers and I got that too. If I’d chosen a different path, I am sure I’d still be writing, but I don’t know if I’d be writing books or teaching, and I wanted to do that. I’d say to be clear about what you want from an MFA program, weigh the pros and cons carefully, and do your research on the programs you’re considering, including talking to alumni and current students. Don’t be shy about that. How they talk about other students, colleagues, and other writers says a lot about the culture. Reach out to faculty, too. All institutions come with challenges and issues, though, and higher education is in flux. But in any decision, I’d say to keep your unwavering focus on the work you want to do and make.

9. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

I would love to witness the professionalization of care and generosity in both our field and in the world generally, and I don’t care if it sounds Pollyannaish. In her poem “Paul Robeson,” Gwendolyn Brooks wrote: “we are each other’s harvest: we are each other’s business: we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” I believe that it heightens the professionalism of the workplace to care about how you treat other people, how your actions and words affect them, to value humanity over profit and fame, and I try to behave and make choices accordingly.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

It wasn’t so much advice as a statement. Chris Abani was one of my mentors in grad school and I remember someone at an event asking him to talk about which genres he wrote in. He writes in all of them, so he said something eschewing the urge to think in terms of genre. He said, “I write books.” I remember thinking: Yes. I want to do that.