This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kimberly Grey, whose debut essay collection, A Mother Is an Intellectual Thing, will be published on December 5 by Persea Books. In this lyrical exploration of motherhood, the parent-child relationship, and language, Grey blends memoir and critical theory to tell a personal story and investigate its meanings for the self and within the larger culture. The narrative moves back and forth in time, from the narrator’s life in the present to consider experiences from childhood through the recent past, particularly involving the author’s troubled interactions with her nuclear family. A chronicle of grief filtered through the mind of an academic and poet, the book charts an intellectual’s attempts to assuage the trauma of loss by considering what great thinkers—from Roland Barthes to C. D. Wright—have said on that and other proximal subjects. The book also functions as a metacommentary on the efficacy of writing and verbal communication, particularly in the face of obliterating sorrow: “It’s taken me thirty years to understand the rules of my mother, ” Grey writes, deploying grammar as a metaphor to understand interpersonal dynamics. “Mostly unspoken. Mostly unfollowable: be my mirror, don’t be my mirror. You are not wanted here, but you are not to leave. Verb contradictions. It’s why I so desire to understand mother as a verb.” Kimberly Grey is the author of the poetry collections Systems for the Future of Feeling (2020) and The Opposite of Light (2016), both published by Persea books. She is the recipient of Stanford University’s Wallace Stegner Fellowship, a teaching lectureship from Stanford, and a Civitella Ranieri Fellowship. Her work has appeared in A Public Space, Kenyon Review, Tin House, and other journals. She is currently a visiting professor of poetry at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

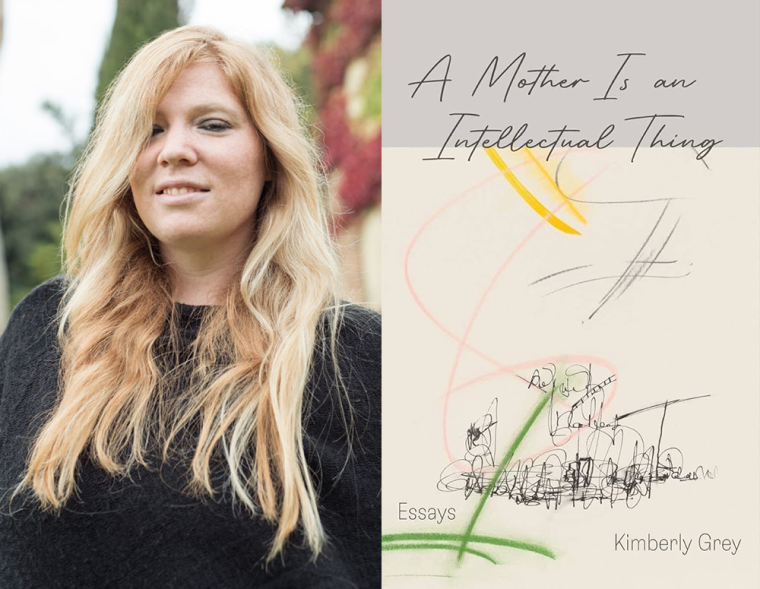

Kimberly Grey, author of A Mother Is an Intellectual Thing.

1. How long did it take you to write A Mother Is an Intellectual Thing?

I became estranged from my entire family in August 2015. About six months later, in early 2016, I began writing the initial sections of the book. I was too traumatized during those early months to write anything, but that entire first year was just about creating little snippets of writing. I was a fellow at Civitella Ranieri in Italy during fall 2016, and that is when the book began in earnest. I wrote the title on my bulletin board in my studio so that I would begin recognizing it as a book and I’d pass by it every morning when I went to make my tea and toast. It became like an echo that felt more like a real sound every day. By spring 2021 the book was fully formed, though I tweaked it a bit until I had no choice but to turn in the final version to my editor. So all in all, it took about five years to complete.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I was conditioned from an early age to never speak out against anyone in my family, to keep family secrets, to never criticize my mother or hold her accountable for anything. This was a kind of implicit, insidious grooming that started in early childhood, so the idea of writing the truth of how I was treated by my mother was terrifying, almost to the point of paralysis. I had to continually give myself permission to write about my true, lived experiences with abuse and scapegoating and how traumatizing and life-altering it has been. But I do think some small fragments of fear never went away, and so the book does employ intellectualization as a sort of protective mask. That made things a little less challenging. Or at least allowed space for the book to happen.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write in my home office mostly. I’m not really a coffee-shop writer, and I tend to not apply for residencies much, as I prefer my own familiar space. I need complete silence to really concentrate on language and form. It takes time to get into that headspace, so I don’t write as often as other writers. I try to make a point to set aside three hours a week for writing, sometimes Sunday mornings. But if I don’t feel like writing during that time, I’ll read or do something else. I’m very much a write-when-it-comes kind of writer. Which often means slower production. But I have no interest in being prolific. I’ve gone months without writing anything. I’ve also written twenty poems in one month. It’s all just dependent on the outside factors and forces of teaching and life.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m currently reading Elaine Scarry’s Dreaming by the Book. It’s this interesting amalgamation of literary criticism, philosophy, and cognitive psychology that explores how writers create art through the act of mental composition. She asks, “By what miracle is a writer able to incite us to bring forth mental images that resemble in their quality not our own daydreaming but our own (much more freely practiced) perceptual acts?” I’m really interested in her assertion that “our freely practiced imaginative acts bear less resemblance to our freely practiced perceptual acts than to our constrained imaginative acts occurring under authorial direction.” The book is teaching me something about perceptual agency that aligns itself with hybrid-genre work.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Probably most central to all my work is Anne Carson. She is a true hybridist, creating books that are artifacts, art-objects, and amalgamations of poetry, art, opera, translation, image, etcetera. I like how many of her books aren’t even classifiable, employing so many different disciplines and modalities that the book asserts its own categorization. For me, meaning is multiplied by the sheer multitude of approaches and disciplines. Other writers that have greatly informed this book and my work in general include Renee Gladman, Roland Barthes, Etel Adnan, and Maggie Nelson.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of A Mother Is an Intellectual Thing?

I was surprised at how hybrid the book became. I started off truly wanting to write a more narrative book of essays. But the more research I did into trauma theory, the more I realized that writing about trauma requires an entirely different approach to narrative and progress. The idea of any kind of continuity or story advancement felt impossible while in the throes of severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). When one is traumatized they are literally stuck, so much so that many trauma therapies work on “unfreezing” stuck memories from the brain using bilateral stimulation (sometimes through eye movements, sometimes through hand buzzers). So the book became this exercise in a different kind of progress, a progression of the mind trying to process and understand trauma. Because of this I found myself moving among prose, poetry, and image; each became its own experimental improvisation toward understanding, toward eventual meaning.

7. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

I read some very early essays in this book to my friend, the wonderful poet Spencer Reece. We were both living at Civitella and walked down the backside of the castle into Umbertide to have a coffee in the center of town. We sat across from each other on these sweet, little sofas, and I read aloud to him in this public space, loud enough that other people could hear me. This was a sort of induction into the work one day becoming public. Afterward we went to this little church in the square, and Spencer, an ordained priest, held my hand and said a prayer for me to overcome my pain. That’s when I knew, for sure, I’d finish the book. No matter what complications or challenges in writing came, I had to write it.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started A Mother Is an Intellectual Thing, what would you say?

This is impossible for me to answer because this is a book I never thought I would have to write. I could never have imagined I’d be exiled and dislocated from my entire family. It was something completely unfathomable to me. I also think there is no “earlier me” that I could possibly access or imagine anymore. Trauma makes before-and-after versions of us, whether we like it or not. For me, my life feels like it has been split into two, and I no longer have access to my before-life or who I was before this estrangement. So the only way to answer this question is to access the me that I was immediately after the estrangement, those first six months when I couldn’t write anything. If I’m being completely honest, I think that I was hoping that this wasn’t real, that my family would want me back and there wouldn’t be a story to write. That my trauma would be corrected by them. That I would—in some magical way—be told I was actually a loved and valued daughter, sister, aunt. The book only came once I realized that was never going to happen, no matter how hard I wished it would. So I would say to that person: You are going to write the book, and it won’t feel like a relief. It won’t cure your pain. It won’t make the world alright or take away your suffering. But it will be the first time you’ve really had a voice. The first time you let yourself write something that feels necessary. And that means something.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I wrote this book while completing my PhD, and my entrance into theoretical research—including trauma, narrative, and psychoanalytic theory—were central to the book’s making. Melding research with memoir and poetry was a new challenge, but it added a sense of veracity, even authenticity to the writing. I feel like the polyvocal conversations I have with other writers, philosophers, artists, and theorists helped to authenticate my own experiences. I also feel like I became a smarter and more well-rounded creative writer by broadening my knowledge of theory and literary criticism.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

My first poetry professor, Stephen Dunn, told me that I had to learn to love lines and sentences as much as ideas. I don’t think I fully understood what he meant back then, but now I know he was instructing me to fall in love with the tension between the line and the grammatical sentence; how the unit of the line itself manifests as a unit of meaning, independent of the sentence but married to it as well: two distinct manifestations of meaning. When I was at Stanford University, the poet Eavan Boland once told me, “If you ignore your autobiography, you will never become an authentic poet.” At the time I did not believe her. I was even angered by her comment. I only realize now that she was granting me permission to write about my life and my family—something I had been conditioned since childhood not to do. I prided myself on my “fictional constructions” and asserted that I came from the Wallace Stevens school of thought, regarding poetry as “the supreme fiction.” But that’s because I did not yet have permission to write about my life. I didn’t think I could. She gave me that, and I am forever indebted to her.