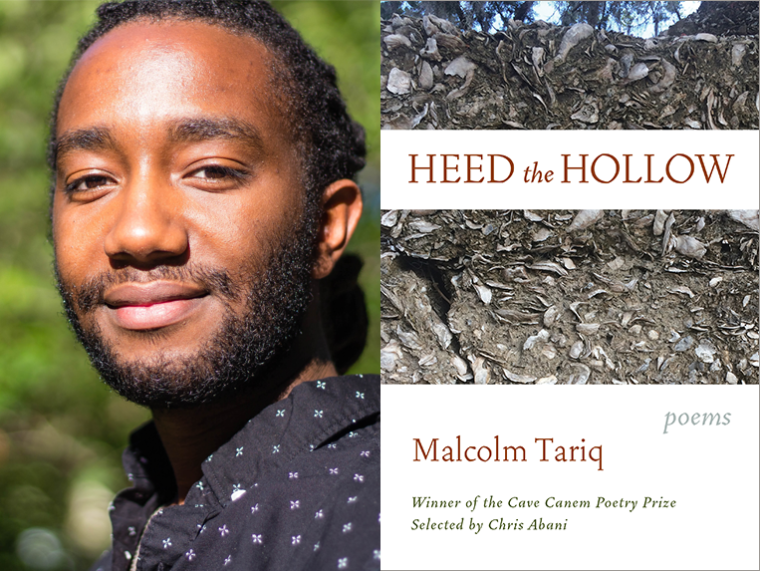

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Malcolm Tariq, whose debut poetry collection, Heed the Hollow, is out today from Graywolf Press. Selected by Chris Abani as the winner of the 2018 Cave Canem Poetry Prize—an annual award for an exceptional manuscript by a Black poet of African descent that includes $1,000 and publication—Tariq’s debut is a complex and expansive exploration of the self, the South, Blackness, and queerness. Each poem is the site of multiple possibilities, the convergence of the past, future, and many, often dissonant, emotions. In the opening poem, “Power Bottom,” Tariq invokes both love and terror, employing humor and double entendre to shift from queer sex to lynching within the same page. In his introduction Abani notes some of Tariq’s conflations may well feel “problematic and uncomfortable,” but they are all the more vital and resonant for this reason. Heed the Hollow, Abani writes, “marks the possibility of a new set of terms to expand on the already beautifully complicated aesthetics of the grotesque.” Malcolm Tariq is also the author of a chapbook, Extended Play. He is a graduate of Emory University and earned his PhD in English from the University of Michigan. Born in Savannah, Georgia, Tariq lives in New York City.

Malcolm Tariq, author of Heed the Hollow. (Credit: Karisma Price)

1. How long did it take you to write Heed the Hollow?

About four years. The writing for Heed the Hollow started in graduate school and grew more deliberately during the dissertation stage. I drafted the first long sequence, “Tabby,” in 2014. In 2016, I went to the Cave Canem retreat for the first time. I believe the first poem I wrote there was “Power Bottom,” which I had been trying to write for months. This was the catalyst. I had a better understanding of the types of poems I was writing and began to see in what direction this new project was moving.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Knowing when to stop adding poems and angles to the scope of what I was trying to do. When the manuscript won the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, I didn’t actually think it was complete. Having a deadline for the manuscript from the publisher helped me be more comfortable bringing the writing process to a close.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

This depends on the genre. Ideally in the morning, but I don’t keep a deliberate writing schedule unless I’m on deadline or have a steady flow of ideas. Writing at home is difficult if I don’t have an office. I love coffeeshops because there is noise, people-watching, and other distractions. For poetry, I usually keep to paper for several drafts before I transition to a computer. My preferred notebook is a sharp-cornered, hardcover Roaring Spring black marble composition book with 20# paper, item number 77461, college ruled—I’m a Pisces and need a line to keep me grounded.

Having a daily writing time hasn’t work for me so far because of school or work. In my last year, I pregamed academic writing by working on a poem. I finished the dissertation in two years by committing to a page per weekday. That’s five pages a week that can be done whenever. I do this sometimes with plays, just so I can stop stalling and get dialogue down on the page for me to work with.

Great ideas happen for me while someone is talking or there is a discussion. It’s a form of active listening but also creation for me. It’s not unusual for my coursework notebooks and conference programs to have concept maps drawn in the margins. This is how I got through attending church as a teenager.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading three things right now. The first, which I’m reading rather slowly, is Derek Walcott’s collection What the Twilight Says: Essays. I’m currently working on a play about slavery in Savannah, Georgia; queer desire; and time travel. For research on this I’m working through Leslie M. Harris and Daina Ramey Berry’s edited volume, Slavery and Freedom in Savannah. I haven’t been reading much poetry lately, but I had to jump into Rage Hezekiah’s debut, Stray Harbor, which is quite beautiful.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

This is difficult for me to answer. If I have to mention one person, I would say Assotto Saint, who is actually getting more recognition now. I only discovered him a couple years ago. I cried the first time I read Wishing for Wings, which has only happened a few times with art, Tupac’s “Dear Mama” and Gayl Jones’s Corregidora among them. Each line in Wishing for Wings is so deliberate that they are almost distinct little poems in their own right. More than this, the care that Assotto put into his work and the production of the work—from the poems to the plays—is so inspiring. That book in particular gives us so much insight into the era in which it was written. It generously illustrates how communities lived through the most challenging years of our experience with HIV/AIDS, and how we live with that in the everyday sense, even now. It also reminds us how much artists of color—at least from the 1960s well into the 1990s—curated their own professional and artistic lives from community resources when there were not other opportunities for them to do so.

6. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

In the original manuscript there was a definition for “tabby” that appeared at the beginning of the collection. I thought this was important because so much of the book depended on knowing about this word and what it meant. The incredible and patient Jeff Shotts, my editor at Graywolf, suggested that we move the definition to the notes section at the end. He was essentially telling me to trust the reader to get to that understanding on their own. As an academic this is often hard for me, because I was taught to be very clear with my argument, leaving little room for doubt. Art, for the most part, is different. Prefacing the poems this way also robbed the reader of having a deeper engagement with the work on their own terms. Jeff’s guidance here also taught me that when poems begin to take the form of a published book, I as a writer should also consider someone else’s experience of reading it for the first time.

7. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Money? The standard work day in the United State is two to three hours too long.

8. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

Why is Gwendolyn Brooks’s Annie Allen out of print? This is criminal. How can we prevent the same thing from happening to Assotto Saint’s Wishing for Wings and Essex Hemphill’s Conditions and Ceremonies?

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

Something that has been helpful for me is sharing poems with writers who aren’t poets. This opens so many possibilities for innovation as well as the small details that I often forget about. One of my most important lessons in the power of images came from a writing group in which I was the only poet. That really changed my relationship to many of the poems in this book.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I went to Emory mainly because of the creative writing program, but I didn’t take any of the workshops because at the time I didn’t trust the undergraduate students there to be serious about craft. I studied English and sociology instead and spent those years reading. One day I was talking to a guy we called J. P.—John Peterson—who was studying philosophy. I told him I took a logic course for math credit but I didn’t think I could take a philosophy course because it was difficult and required too much thinking. His response was that everyone had a philosophy of some sort and that writing was my philosophy. This was pivotal for me because in my independent study I was learning how to say things, I wasn’t concentrated on what I was saying, why I was saying it, and who I was speaking to and with.