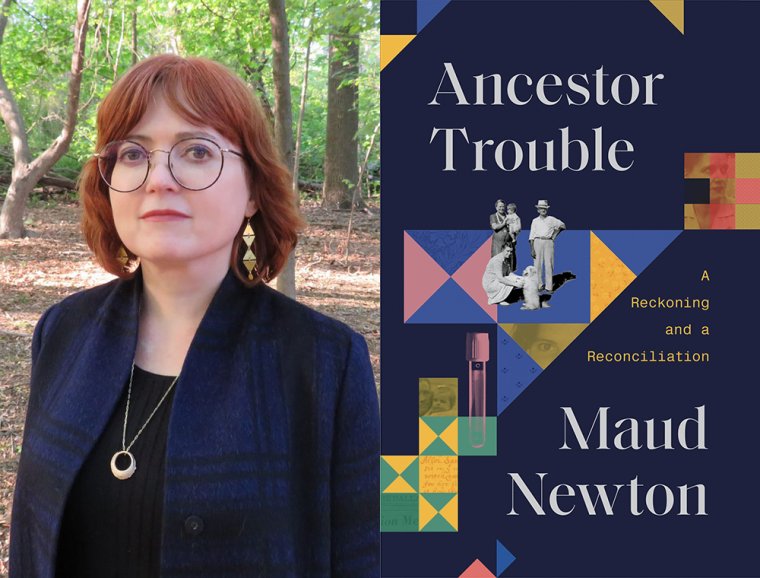

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Maud Newton, whose first book, Ancestor Trouble: A Reckoning and a Reconciliation, is out today from Random House. “I came into being through a kind of homegrown eugenics project. My parents married not for love but because they believed they would have smart children together. This was my father’s idea, and over their brief courtship he persuaded my mom of its merits,” Newton writes early on in her debut, setting the stage for the story of her wildly unconventional Southern family, including her father, an aerospace engineer turned lawyer who extolled the virtues of slavery and obsessed over the “purity” of his family bloodline, which he traced back to the Revolutionary War. Ancestor Trouble traces Newton’s attempt to use genealogy to expose the secrets and contradictions of her own ancestors, and to argue for the transformational possibilities that reckoning with our ancestors has for all of us. “Newton takes this extraordinary journey not only for herself, but to illuminate this present moment in this country we all love,” writes Honorée Fanonne Jeffers. “‘Look,’ she tells us. ‘This is America. This is how we came to be.’” Maud Newton is a writer, critic, and former lawyer. Her writing has been published in Harper’s magazine, the New York Times Magazine, Bookforum, Narrative, the New York Times Book Review, Tin House, Granta, the Los Angeles Times, Oxford American, and elsewhere. Born in Dallas and raised in Miami, Florida, she lives in Queens, New York.

Maud Newton, author of Ancestor Trouble: A Reckoning and a Reconciliation.

1. How long did it take you to write Ancestor Trouble?

I worked on it as a book for seven years, a little less than eight counting the months I spent writing an article about genealogy and my family for Harper’s. But if I’m honest, this is a tricky question to answer. I started writing about my genealogical research on my blog in 2007, and I’ve been writing about my family since I first learned to write.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Purely on a technical craft level, the most challenging thing was figuring out how to write about the different avenues I went down in the same voice I was sharing my family stories. The book centers on my family history but also considers genealogy; genetic genealogy; genetics, epigenetics, and ancient ideas about what we call heredity; psychoanalytic conceptions of ancestors and their importance for us; debates about intergenerational trauma; generational wealth; systemic racism; spiritual ideas of the importance of ancestors across the world and across time; and how we can use troubled family histories for the better. I knew I was asking a lot of the reader to follow me through all of this, and I did my best to write it all truthfully and without pretension.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I do most of my best writing in the middle of the night but I write at all times of day except the early morning. I’ve always been a night owl. When I was younger I wrote everywhere. The subway was a favorite venue. Nowadays I do a certain amount of writing in bed or in the rocking chair my great-grandfather made in the early 1900s that I like to sit in with my coffee in the morning. But even before the pandemic I’d worked my day job from home for many years, and between book and essay writing and holding down a job that also involves a lot of writing, for the most part I just shuttle between my writing desk and my work desk. Weekends are a break in the sense that I only need to show up at one desk. I have dogs who get me outside on walks every day, but otherwise I generally feel like I should be writing whenever I’m not.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Imani Perry’s South to America, Tanais’ In Sensorium, a story collection edited by Hillary Jordan and Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan called Anonymous Sex, which is a sort of guessing game in that you don’t know which piece is written by which contributor. I’m also reading some books for my next project.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I love the essays of Sheree L. Greer, who writes about addiction, family, and much more, and I’m looking forward to reading her stories at book-length one day, in whatever form that takes.

6. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

Because of my other job and maybe also my general disposition, I’m a little more at a distance from writing communities and the book publishing industry than a lot of writers, so I don’t feel equipped to speak to the day-to-day, but I hope publishers will commit themselves long-term to the inclusivity they promised for BIPOC and LBGTQ+ writers in the summer of 2020.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

So many things, from both of them! But my editor encouraged me early on not to be afraid of what I thought of as the ghost-story aspects of the book. With a different kind of editor, this book could easily have ended up being a lot more cerebral and a lot less satisfying to me.

8. What, if anything, will you miss most about working on the book?

It was easy to feel tender toward the world, committed to making the best and truest book I could, and not invested in the outcome while I was holed up working for so long. I hope to hold on to some of that spirit as the book moves out to find its readers. I’ll also miss all of my arcane research. I had never expected to immerse myself quite so deeply in Aristotle.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

That’s a tough question. I’m grateful beyond words to my friend Elizabeth Bachner, an incredibly talented writer and a fantastic conversationalist and thinker, who read many iterations of many parts of this book and always responded with gentle enthusiasm, no matter what a mess each draft was. She very rarely offered criticism, only excitement, and only in hindsight do I realize how much I needed that as I worked.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

One bit of advice I love from James Baldwin that rings true for me is that writers inevitably write out of their own experience. “Everything,” he said, “depends on how relentlessly one forces from this experience the last drop, sweet or bitter, it can possibly give.”