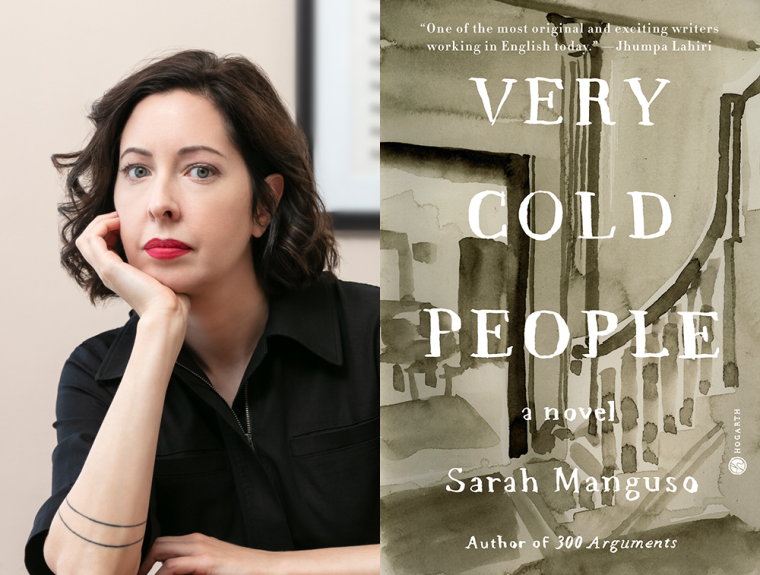

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Sarah Manguso, whose first novel, Very Cold People, is out today from Hogarth. The setting of Very Cold People, Waitsfield, Massachusetts, is cold in both the literal and metaphorical senses. Heavy snow blankets the streets in winter, but the town is cloaked in loneliness and secrecy year-round. Coming of age in this environment, the young narrator, Ruthie, lives in a dissociated state: “I spent those days feeling half-there, not quite committed to that life.” But she is nevertheless watchful, and through her eyes the reader is introduced to the nuanced class dynamics and legacy of violence in Waitsfield, and by extension, the many towns like Waitsfield in America. “Very Cold People knocked me to my knees,” writes Lauren Groff. “So precise, so austere, so elegant, this story is devastatingly familiar to those of us who know the loneliness of growing up in a place of extreme emotional restraint.” Sarah Manguso is the author of eight books. Her previous book, 300 Arguments (Graywolf Press, 2017), was named a best book of the year by more than twenty publications. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Hodder Fellowship, and the Rome Prize. Her writing has also appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the New Yorker, and O, the Oprah Magazine, among other publications. She grew up in Massachusetts and lives in Los Angeles.

Sarah Manguso, author of Very Cold People.

1. How long did it take you to write Very Cold People?

In 2015 I sent an e-mail to my agent that read, “I might be writing a novel.” I was testing myself, seeing if I could actually say that to someone. But I’d been wondering how to exorcise Massachusetts from myself for more than thirty years. Very Cold People finally did it.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Leaving aside my received ideas about what a novel was. I knew the Massachusetts book had to be a novel, but I hadn’t begun writing any of my other books with any fixed ideas about their form. And of course the novel is not a form! It is a name for a very large number of possible forms. But for a long time I was terrified that knowingly writing a novel would trick me into producing a boring novel, the average of all existing novels. I got over the fear of writing an average novel only by writing slowly through that dumb fear until the book was done. As soon as I finished it the fear dissipated, and I immediately started writing another novel.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Wherever, whenever, and as much as possible. Until recently writing was a mostly interstitial activity for me; paid work and parenting and household management and illnesses took up most of my time, and those activities didn’t leave long stretches of time to write. But I was almost always thinking about writing, and I integrated the other parts of my life, as much as I could, into the writing. And I still do that.

4. What are you reading right now?

Samantha Hunt’s forthcoming The Unwritten Book: An Investigation.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I immediately freeze when asked to pluck a single name out of the panoply. American writers ought to read more work in translation, and Katie Kitamura has listed some excellent English-language publishers of translated work in her own Ten Questions interview. There are also plenty of English-language writers who are underrecognized. The way to find them is simple: Read small-press books. If you are able, go to independent bookstores, used-book emporia, book swaps, and library sales and browse the physical shelves. Don’t let an algorithm tell you what to read. Disobey the algorithm.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

At the risk of sounding coy, I’ll say that the biggest impediment to my writing life was recently removed from my life. I currently feel unimpeded.

7. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

There are so many kinds of writers with all sorts of lives! I prefer to tailor advice to the individual, when asked. And there are so many different sorts of MFA programs now. But I don’t think an MFA is strictly necessary or sufficient.

8. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

That the anchor story, the main relationship depicted in the book, was between the narrator and her abusive mother. As soon as my editor said that, I realized it was true, and had been true all along.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

Sheila Heti, who vigorously corrects my course when I stop writing like myself and start pandering to some imagined general audience. She lives on another planet where artists don’t worry constantly about money. The name of that planet is Canada.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

This isn’t exactly advice, but during the first semester of my poetry MFA, I confessed to my teacher Jorie Graham that I’d started writing short prose pieces and couldn’t stop and wasn’t writing poems anymore. I was disappointed in myself and felt that I was letting everyone down—my teacher, the program, and the foundation that was paying for me to become a poet. Jorie said, “So?” That one-word response gave me permission to write whatever I wanted to write for the rest of my life.